If you are ever in Essex County, Massachusetts, there is an interesting cemetery within the Maudslay State Park in Newburyport. It is a pet cemetery and features seven gravestones of beloved pets that once belonged to the wealthy Moseley family.

Continue readingPlease, I'm in a bit of trouble.

I sure hope you won't rat me out. I know I haven't been around the Vita Brevis in a while, but I had to tell someone. You see, I've fallen in with a bad crowd. I've become something of a (gasp)…genealogical heretic. Recently, while..

Continue reading →In the course of their research, genealogists often need to identify an ancestor’s origins before they arrived in the United States. There are many types of records that can be used for this research, with varying degrees of usefulness. Naturalization records are an..

Continue reading →A father attempts to enumerate his household for the census-taker while a few of his children hide from view, foiling his efforts. Painting from 1854, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Many researchers assume that state and territorial census records are of limited value..

Continue reading →I hardly remember the experience of using a card catalog—those clunky piece of furniture which were once an inescapable aspect of research. When I came of age, libraries were already phasing out physical card catalogs in favor of digital databases. I do have a small..

Continue reading →Those of us researching our Irish roots are always hoping to discover our family’s place of origin in Ireland. But even after searching diligently for every scrap of information possible in U.S. records, we are often left frustrated. Too many U.S. records simply list..

Continue reading →We can use DNA as another source in our genealogical research toolbox to help discover family connections and break down brick walls. DNA evidence and traditional documentation, like vitals and census records, should be used to help prove relationships between two..

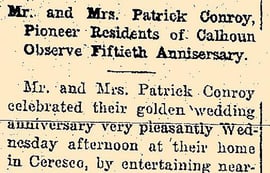

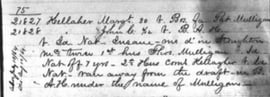

Continue reading →I wrote about Margaret (Mulligan) Kelleher and her infant son John Cornelius Kelleher a few months ago in a previous Vita Brevis post. While I thought the trail had..

Continue reading →This past May, I taught a class on 18th century Pennsylvania and highlighted some documents I had discovered for my Pennsylvania ancestors. As I prepared for the..

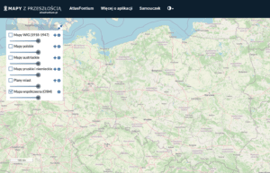

Continue reading →Recently, the Tadeusz Manteuffel Institute of History, part of the Polish Academy of Sciences, unveiled a new interactive map feature on their website: Mapy z Przeszłością (Maps of the Past). The online tool superimposes..

Continue reading →