A painting by artist John Carwitham shows the Port of Philadelphia in 1752. Source: Hiddencityphila.org.

A painting by artist John Carwitham shows the Port of Philadelphia in 1752. Source: Hiddencityphila.org.

This past May, I taught a class on 18th century Pennsylvania and highlighted some documents I had discovered for my Pennsylvania ancestors. As I prepared for the class, I reflected on one of the biggest brick walls I had encountered in my own family research, and thought about what advice I’d give to someone researching their own colonial ancestors. After looking back at my own challenges and triumphs, I came up with three recommendations: don’t trust family lore or uncited published genealogies, consider various spellings of the surname, and visit the local historical society.

For years and years, I tried to breakdown a brick wall that seemed to plague every descendant of my 6th great-grandfather William Ashton of Bristol, Bucks County, Pennsylvania. A quote from one of the many compilations by his descendants had this to say about William and his ancestry:

"The first Ashton, in this country, of our family was neither banished for crime nor traded for tobacco, but belonged to one of the oldest titled families of England. He was, as I understand, disowned because he espoused the Quaker faith. This Ashton family were related to the Hutchinson’s of England, one of whom, Thomas Hutchinson, was colonial governor of Massachusetts."

At the time, I was a young and inexperienced researcher. The information seemed legitimate and was backed up by several genealogies found in libraries in Ohio and Nebraska, where William’s descendants settled. Many accounts even claimed that the Ashton family came from Lancashire, England, and that William immigrated to Pennsylvania under the direction of William Penn. 2 Now, simple math told me that the last statement was unlikely, since Penn died in 1718 and my ancestor was probably born about 1740. However, I kept an open mind, and considered that it was probably William’s father or grandfather who came over with Penn.

I couldn’t begin to count the number of emails and blog posts that all reiterated a version of the same question: “I’m trying to find the parents of William Ashton of Bucks County, Pennsylvania. The first of this family was from Lancaster, England… Would you be willing to share your tree?” We all had the same information, so it was obvious the story of the Ashton family had spread far and wide, and everyone’s search efforts centered solely around these details. As years went by and I failed to identify William’s parents, I began to come to terms with the fact that sometimes, the records just don’t exist. But I wasn’t a quitter! Looking back, it was the three suggestions I detailed above that helped me finally break through the long-standing brick wall on my mother’s paternal line.

Second Street north from Market St. with Christ Church, Philadelphia. From Birch's Views of Philadelphia, 1800. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Second Street north from Market St. with Christ Church, Philadelphia. From Birch's Views of Philadelphia, 1800. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

My 6th great-grandfather William Ashton seemed to appear out of thin air in Bristol in 1761, showing up in tax records shortly after marrying Pheabe Hutchinson, a Quaker who had been disowned by her family for her beliefs, at Christ Church of Philadelphia on 27 July 1761.3 Previous tax records for Bucks County had no entries for an Ashton prior to William’s appearance in 1761. I noted at the time that an Edward Ashton was taxed as a single man in Bristol in 1766, but searches for him always came up empty.4

William and Pheabe’s son Samuel, my 5th great-grandfather, was born in February of 1771, and was orphaned by age three.5 Family lore said that he had one sister who died in a fire when she was a young woman, but I’ve never been able to locate any records for their births or information pertaining to the deaths of Samuel’s sister or mother.6 I was able to track down an Administration for William, who died intestate, which was filed in 1774.7 However, the names mentioned in estate records—like Elizabeth Adair, who received the largest sum from the estate—didn’t mean much to me at the time.8 Unfortunately, I couldn’t locate any records for Elizabeth, but I was able to verify from tax records that there were Adair families living in Bucks County around the same time as William Ashton.9

For months, my home office walls were a shrine to all the Ashtons of Christ Church of Philadelphia, where William and Pheabe married, as I traced every one of those men who were already proven to be descendants of a titled English family from Assheton-under-Lyne in Lancashire, England.10 These same Ashtons, also spelled Assheton, were considered a very prominent family in Philadelphia, and many are memorialized in stone in the isles of Christ Church or buried in the Christ Church Burial Ground with contemporaries like Benjamin Franklin, who was also a member of the church. 11 It seemed like a logical approach, since I was related to this family on another Pennsylvania ancestorial line. After countless hours of building out family trees for Ashtons recorded in baptisms, burials, church minutes, and pew rentals, the first seed of doubt about this Ashton line was planted—if my ancestor William was part of such a prominent family, then why was there no trace of him?

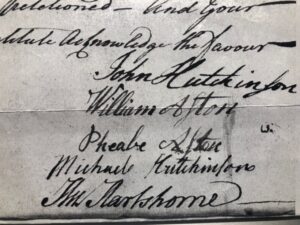

Eventually, I made an unplanned visit to the Bucks County Historical Society at the Mercer Museum Library in Doylestown, Pennsylvania—which I highly recommend—and before I knew it, I was on my way to knocking down my longstanding brick wall. When I checked in at the front desk, with less than an hour before closing time, the clerk asked me the family names I was searching for and recognized the name Hutchinson. Twenty minutes later, she came out from the back room with a folder containing original Orphan Court documents from 1762 signed by my 6th great-grandparents.12 At first glance, it looked like William and Pheabe signed their last name Aston, and it took me a few minutes to realize they had actually signed their names with the “Old English” [ ʃ ],used to represent “s” or “ss” and often pronounced like the modern English “sh” sound.13 However, I noted that my ancestors John Hutchinson and Michael Hutchinson had also signed their names using the [ ʃ ] character. I had probate records signed by Pheabe in 1766 and an estate inventory signed by William in 1767, so I knew they clearly spelled their name Ashton a few years later, but I sat there staring at their signatures and asked myself—when looking for William’s father, should I have been looking for an Aston?

Bucks County Historical Society, Doylestown, Pennsylvania, Orphans Court, Bucks County, book E, estate of Jno. Hutchinson, 16 March 1763, page 134.

Bucks County Historical Society, Doylestown, Pennsylvania, Orphans Court, Bucks County, book E, estate of Jno. Hutchinson, 16 March 1763, page 134.

Twenty minutes before the historical society closed, I was raced back to the microfilm collection to power through every probate record in Bucks County, starting with the letter “A,” and frantically printed any record close to the name Ashton or Aston. As I sat in my car reviewing my stack of papers, I began to get the sense that my 6th great-grandfather William Ashton was not in fact an Englishman, as all the family lore and genealogies claimed.

One of the probate records I hastily printed turned out to be an Administration for Samuel Aston, who died intestate in Bristol, Bucks County in 1752. The administrators for his estate were William Adair and Edward Adair.14 There was that name surname again—that very Scottish or Northern Irish surname. I immediately called my uncle, a direct male descendant of William Ashton, and finally convinced him to take a Y-DNA test. As I waited patiently for the test results, that little voice inside me kept telling me I was looking for an Irish or Scots-Irish ancestor, but I still couldn’t locate any records to help me expand the family of William Ashton.

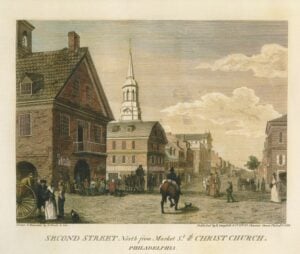

By this time, many years had passed, and my knowledge and sleuthing skills had improved. I knew that many Irish immigrants came over as indentured servants, and since conventional research methods had failed me, I resorted to an unconventional method—Google search. I searched the terms “Ashton Irish servant,” and up popped a runaway servant advertisement, placed in The Pennsylvania Gazetteon 7 August 1766, that showed “Edward Ashton, born in Ireland, by Trade a Taylor, served his time in Bristol, Pennsylvania. 15 A reward for his capture in New Jersey was offered by John Breeding, and when I dug a little deeper, I found that John was married to woman named Ann Ashton.16

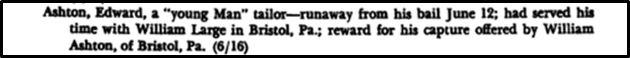

A similar runaway advertisement was also posted in The New-York Mercury , but it stated that the reward for Edward’s capture in Pennsylvania was being paid by William Ashton of Bristol, Pennsylvania.17

Kenneth Scott, Genealogical Data from Colonial New York Newspapers, Genealogical Publishing Company, reprinted 2000, pg. 115.

Kenneth Scott, Genealogical Data from Colonial New York Newspapers, Genealogical Publishing Company, reprinted 2000, pg. 115.

I was trying to tamper down my excitement, but it wasn’t long before I could celebrate. My uncle’s Y-DNA test revealed that he was an exact match to a man with the surname Ogston, whose line went back to Aberdeen, Scotland in the early 1600. This helped bolster my suspicions that the Ashton family of Bucks County were likely Scots-Irish emigrants from Ulster.

As for Edward’s relationship to William Ashton, I still haven’t found primary documentation to prove how they were related, but the trail for Edward didn’t go cold. Using migratory roads out of Pennsylvania, I searched for Edward along the Great Wagon Road from Philadelphia to Augusta, Georgia and was able to locate him near Augusta in Richmond County in 1782. Records show that he had his land confiscated, and was permanently banished from the state for “traitorously Adhering to the King of Great Britain, by Aiding, Assisting, Abetting and comforting the Generals and other officers Civil and Military of the said King to enforce his Authority.”18

After Edward was exiled from Georgia, he appeared in records in the Spanish settlement of St. Augustine, Florida, where documents showed that he was a tailor and planter, a former British subject born in Ireland about 1749, and that his parents were Samuel Ashton and Margarita O’Dair.19

For more years than I like to admit, this brick wall haunted me. I could have saved myself a lot of time if I had not trusted family lore or published genealogies, had considered that even a simple surname may have been spelled differently, and if I had visited the Bucks County Historical Society a lot sooner!

Notes

1 Karl H. Weaner, The Ashton Family,Defiance Public Library, Defiance, Ohio, pg. 2.

2 Email to Kimberly Mannisto [address for private use only], Farmington Hills, Michigan, sender unknown, 17 March 2005, abstracted information for the Ashton Family prepared by Laura Vail, great-granddaughter of Samuel Ashton.

3 Christ Church of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Parish Registers , “Marriages 1709-1913,” philageohistory.org; William Wade Hinshaw, Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy,“U.S., Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, Vol I-VI, 1607-1943, Ancestry.com, Vol. II, pg. 1004 and Terry McNealy, Bucks County Tax Records 1693-1778 , Bucks County Historical Society, Doylestown, Pennsylvania, Bristol, pg. 37.

4 McNealy, Bucks County Tax Records 1693-1778, Bucks County Historical Society, Doylestown, Pa, pg. 41.

5 Weaner, The Ashton Family,pg. 3

6 Weaner, The Ashton Family,pg. 3.

7 Bucks County, Pennsylvania, Register of Wills, “Wills, 1713-1906,” Bucks County Historical Society, Doylestown,Estate of William Ashton, no. 1417, 1773.

8 Bucks County, Pa, Register of Wills, “Wills, 1713-1906,” Ashton, pg. 8.

9 McNealy, Bucks County Bucks County Tax Records 1693-1778 , Historical Society, Doylestown, Pa, pg. 41.

10 John W. Jordan, LL. D., editor, Colonial Families of Philadelphia, Vol 2, The Lewis Publishing Company, 1911, pg. 1131.

11 Christ Church of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Parish Registers , “burials 1709-1900” and “Pew Rentals 1778-1785,” 17philageohistory.org.

12 Bucks County Historical Society, Doylestown, Pennsylvania, vertical file for Hutchinson, Petition of Ann Hutchinson, Bucks County Orphan Court records, Book E, pg. 309, 16 March 1762.

13 California State University Northridge, “The Long S,” 22 January 2019, library.csun.edu.

14 Bucks County, Pennsylvania, Register of Wills, “Wills, 1713-1906,” Bucks County Historical Society, Doylestown,Estate of Samuel Ashton, no. 804, 1752, pg. 2.

15 Irelandoldnews.com, “Runaway Servant Ads,” posted in The Pennsylvania Gazette,7 August 1766.

16 irelandoldnews.com, Runaway Servant Ads, 1766 and Archives and History, Madison, New Jersey, Greater New Jersey United Methodist Church Commission, “New Jersey, U.S., United Methodist Church Records, 1800-1970,” Salem County Marriage Records, pg. 4.

17 Kenneth Scott, Genealogical Data from Colonial New York Newspapers, Genealogical Publishing Company, reprinted 2000, pg. 115.

18 Allen D. Candler, The Revolutionary Records of the State of Georgia, Volume 1, The Franklin-Turner Company, 1908, pgs. 373-387.

19 Shirly Joiner Thompson, The People of East Florida During the Revolutionary War- War of 1812 Period,” unknown publisher, 1982 and Helen Hornbeck Tanner, “The Delaney Murder Case,” The Florida Historical Quarterly, Florida Historical Society, Volume 44, No. 1, Article 15, pg. 140.

Share this:

About Kimberly Mannisto

Kimberly Mannisto earned her B.A. in English with an emphasis in creative writing from Western Michigan University. She joined American Ancestors/NEHGS in Research and Library Services; she also is a certificate holder from the Boston University Genealogical Research Certificate program. She was introduced to genealogy at a young age and has over 30 years of experience in research and report writing. Areas of expertise: Early Pennsylvania settlers, Colonial New Jersey, Quaker records, Midwest (Michigan and Ohio), Finnish, DNA, Descendancy research, Scottish and English hereditary peerage titles, and Scottish genealogy with a particular interest in genetic markers and male clan descendancy.View all posts by Kimberly Mannisto →