Genealogical clusters develop when offspring of families marry spouses who are related to them by blood, marriage, social position, or wealth—often continuing for generations of marriages.

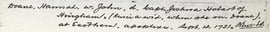

I have written about clusters before , I often uncover them while researching..

Continue reading