My interest in genealogy sprouted at an early age, when my father would tell me stories he heard as a child about my great-great-grandfather, Christopher McNanny. He recounted that Christopher served as a drummer boy during the Civil War, and endured the amputation of both his legs due to wounds sustained during battle. As I got older and more serious about genealogy, I found out that Christopher was not actually a drummer boy, but a private who served in Company G of the 106 th New York Infantry Regiment. He also only had one of his legs amputated.

My interest in genealogy sprouted at an early age, when my father would tell me stories he heard as a child about my great-great-grandfather, Christopher McNanny. He recounted that Christopher served as a drummer boy during the Civil War, and endured the amputation of both his legs due to wounds sustained during battle. As I got older and more serious about genealogy, I found out that Christopher was not actually a drummer boy, but a private who served in Company G of the 106 th New York Infantry Regiment. He also only had one of his legs amputated.

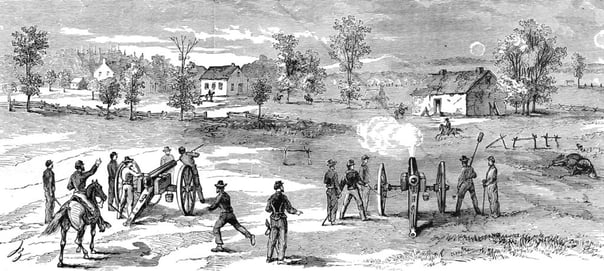

Before enlisting, Christopher resided in Madrid, New York, and was the husband of Margaret White. Christopher and Margaret had four children before the Civil War, including my great-grandmother Sarah McNanny, who eventually came to Brookline, Massachusetts in the 1870s. According to Christopher's pension file, he mustered into Company G on 19 August 1862, at Camp Wheeler in Ogdensburg, New York. Company G was composed of men from Madrid as well as nearby Stockholm, New York, and took part in battles such as the Battle of the Wilderness, the Battle of Cold Harbor, the Battle of Spotsylvania Courthouse, and the Battle of Summit Point.

My fascination with Christopher grew, and I wanted to learn as much as possible about his service to the country. I scoured various websites dedicated to the 106 th Regiment. However, while many of these websites detailed the campaign and battles of the 106th, I yearned for more specific information on Christopher's personal experience. One of my first sources was Christopher's obituary, published in The Madrid Herald on 8 April 1909, which provided a high-level overview of his service, though with some errors.

I decided to try to connect with experts on the 106th, to see if they could offer any information or steer me in the right direction. I found an expert through a website I discovered via a Google search, and sent an email requesting any information on Christopher. Later that same night, I received a bizarre response that left me astounded.

The email contained an impressive level of detail. It began by describing the campaign history of Company G, detailing the names and locations of the battles they fought. It then revealed that the little toe on Christopher’s left foot had been wounded by a minié ball (a type of bullet) during the Battle of Summit Point in West Virginia on 21 August 1864. This wound eventually led to the amputation of his left leg below the knee on 21 September at Jarvis U.S. General Hospital in Baltimore. As it turns out, all this information was preserved from Christopher’s medical case file alongside a surprising relic: the amputated foot itself.

I learned that Christopher's foot was retained after his surgery as a teaching specimen, and has since remained in the anatomical collection of the National Museum of Health and Medicine, formerly the Army Medical Museum. Discovering his preserved skeletal foot has been one of the strangest discoveries of my genealogical research.

In May of 1862, during the Civil War, the Army Medical Museum was established by Surgeon General William Hammond. The museum's purpose was to collect and study specimens related to military medicine and surgery. One of the museum's first and most significant projects was the study of preservation techniques for amputated limbs. At the time, amputation was considered standard procedure to save soldiers’ lives from injuries sustained in battle. However, the mortality rate for these procedures was high, due to the risk of post-operative infection. The museum's researchers sought to improve the survival rate of patients by examining different preservation methods such as refrigeration and chemical treatments. The study's findings were instrumental in improving the outcomes of amputations and saving countless lives during the Civil War.

The Army Medical Museum continued to collect specimens and conduct research, eventually becoming the National Museum of Health and Medicine in 1989. Today, it remains a vital resource for medical researchers and historians. Christopher's leg became part of what is now the NMHM collection of Civil War specimens. 1

Soon after receiving this news, I contacted the NMHM to see whether Christopher’s foot was still retained in their collections, and whether I could see it. A few days later, they sent me a series of photographs. As I looked at the images, I couldn't help but imagine the life the owner of that left foot had lived. Christopher was born in Ireland, made the journey across the Atlantic as a child, became a farmer in Northern New York, fought for the Union in the Civil War, and ultimately lost his foot in battle for his country. Given the lack of post-operative care for amputees at the time, I cannot imagine Christopher's life was easy after he was discharged on 1 June 1865, but he did live for almost another 45 years before passing away in Madrid, New York, on 15 April 1909. Whatever difficulties he may have faced during his life, his obituary in the Madrid Herald speaks highly of him:

"In addition to his service as a good soldier in his country's defense, Mr. McNanny deserves honorable remembrance as a respectable, industrious citizen, a good father to his family, a kind husband, and a good neighbor."

As a genealogist, I am proud to have uncovered Christopher's remarkable life and his unique legacy. However, as a descendant, the quality of his character is the legacy that makes me proudest.

Notes

1 https://medicalmuseum.health.mil/index.cfm?p=visit.history

Share this:

About Don Reagan

In Don’s role, as Chief Business Development & Marketing Officer, he is responsible for enhancing revenue-generating activities, driving scalable financial growth, and expanding membership for the New England Historic Genealogical Society. Don’s career has spanned market research, big data, and HR analytics. In his career, through business development and marketing, Don has been responsible for growing early-stage companies into high growth businesses with a portfolio of Fortune 500 clients. Don earned his bachelor of science and MBA from Clarkson University where his focus was business and technology management. Don also earned a bachelor of art in history from Clarkson. A native of Brookline, Massachusetts, Don has been fascinated with family history since a young age starting with Don’s father telling him of a great-great-grandfather named Christopher and knowing only he lived near Malone, New York, served in The Civil War and was wounded. The mystery behind Christopher is what pushed Don to seriously start researching his family and over the past decade has discovered roots in Saint Lawrence County, NY; Northumberland County, New Brunswick, Canada; numerous counties in Ireland, and Brookline.View all posts by Don Reagan →