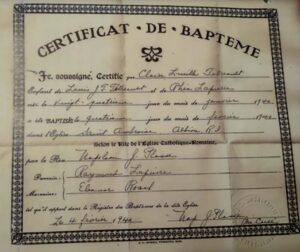

While reviewing my family records recently, I found myself remarking to my wife how interesting it was that my grandmother’s baptism record from St. Ambrose Church in Albion, Rhode Island, was written in French—despite the fact that, as far as I knew, my grandmother did not speak the language. I knew my family had deep French-Canadian roots, and I was well aware that the Blackstone Valley, where my grandmother’s family had lived, was a popular destination for French-Canadian immigrants. Further research revealed exactly why Woonsocket bills itself as La Ville la Plus Française aux États-Unis—the most French city in the United States.

While reviewing my family records recently, I found myself remarking to my wife how interesting it was that my grandmother’s baptism record from St. Ambrose Church in Albion, Rhode Island, was written in French—despite the fact that, as far as I knew, my grandmother did not speak the language. I knew my family had deep French-Canadian roots, and I was well aware that the Blackstone Valley, where my grandmother’s family had lived, was a popular destination for French-Canadian immigrants. Further research revealed exactly why Woonsocket bills itself as La Ville la Plus Française aux États-Unis—the most French city in the United States.

The area that now includes the city of Woonsocket, Rhode Island was first inhabited by three indigenous tribes: the Nipmucs, Wampanoags, and Narragansetts.1 In the 1660s, Richard Arnold Sr., an associate of Roger Williams, laid claim to land along the Blackstone River and built a sawmill on the Rhode Island side.2 The area remained relatively undeveloped through the eighteenth century until the Industrial Revolution, when the city’s proximity to water made it an attractive location for new textile mills. Through the nineteenth century, the once small community’s population exploded, and manufacturing grew exponentially. The city was part of Wrentham, Massachusetts until 1747, when the land was ceded to Rhode Island and the town of Cumberland was founded.3 Woonsocket remained part of Cumberland until 1867, when three villages were united to form the city of Woonsocket: Woonsocket Falls, Social, and Jenckesville. Four years later, three additional villages were added from the town of Smithfield—Hamlet, Bernon, and Globe—forming the city’s current boundaries.4

Woonsocket’s prosperity in the nineteenth century was due almost entirely to the textile industry that drove the local economy. Across New England, rapid industrialization was supported by the labor of immigrants, particularly French-Canadians from Quebec who came in search of employment opportunities. This mass exodus, known as the “Great Migration” or the “Quebec Diaspora,” occurred between approximately 1840 and the Great Depression of the 1930’s, due in large part to overcrowding in rural areas of Quebec.5 The growing textile industry made New England a perfect choice for settlement. Many Quebecois immigrants found work in the mills of northern Rhode Island, with the vast majority arriving in the Blackstone Valley between 1865 and 1910.6

The rapidly expanding Quebecois population led to the establishment of L'Eglise du Precieux Sang (The Church of the Precious Blood), the Woonsocket’s first French-Canadian parish, which was organized in 1872.7 In the second half of the nineteenth century, French-speaking parishes were formed throughout New England, and it was estimated that by 1899 there were 120 in the region.8

It should be noted that while French-Canadians comprised a vast majority of the French-speaking population in Woonsocket, the Quebecois were far from the only French speakers in the city. In the 1910 census, 424 residents of Woonsocket were recorded as having been born in Belgium, and just under half (211) of those recorded spoke French. That same year, there were 407 French-speaking Belgians in the entire state of Rhode Island, meaning that more than half of this population (51.8%) resided within Woonsocket.9 Woonsocket was also home to many residents who were born in France, peaking in 1920 with 777, representing 41% of all Rhode Islanders born in France.10

Like many other immigrant groups, the French-Canadians who arrived in Rhode Island faced xenophobic discrimination for their cultural background as well as their religious beliefs, which were overwhelmingly Roman Catholic. In 1881, a published report referred to the Quebecois immigrants as “the Chinese of the Eastern States” in reference to their willingness to perform hard labor for low wages as well as their loyalty to their language and culture.11

Due in large part to its significant French-Canadian population, Woonsocket was chosen as the location for the headquarters of Union Saint-Jean-Baptiste d’Amerique, a Franco-American benefit society established in 1899 which eventually became the largest French Catholic fraternal organization in the United States.12

The French-Canadians of northern Rhode Island brought a rich cultural history with them, and this culture soon became a significant part of the fabric of the area. The language that these immigrants carried with them transformed over time to become its own distinct vernacular known as New England French. Conversations were often carried out in public in this language, and in some towns bilingual signs were not uncommon. New England French was first identified as a distinct dialect from Canadian French in Modern Language Notes, published in 1898, which identified the language’s unique features.13 French-speakers were so numerous across New England that there were more than 250 newspapers published exclusively in French up until the middle of the twentieth century. Woonsocket alone had fifteen different newspapers published in French beginning in 1873, with Courrier du Rhode-Island continuing to run through 1942.14

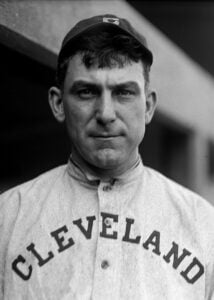

Any discussion of the French-Canadian culture of Woonsocket would not be complete without mentioning perhaps the city’s most famous son: Napoleon “Nap” Lajoie, an inductee in the first class of the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Lajoie was born in Woonsocket on 5 September 1874 to Jean Baptiste and Celina (Guertin) Lajoie.15 He became a local baseball legend before he was scouted and signed by the Philadelphia Phillies in 1896. Eventually, Nap Lajoie would go on to become the most high-profile individual ever born in Woonsocket, and an excellent representation of the French-Canadian community.

Knowing this, the question now becomes: Was Woonsocket really the most French city in America? From a statistical standpoint, it certainly could stake this claim, at least between 1910 and 1920. A study from 1913 reported that Woonsocket ranked:16

- 5th among all cities in the United States in number of French-Canadian citizens;

- 6th among all cities in the United States in number of French citizens (French Canadian and French-born); and,

- 1st in French-speaking population by percentage of total population.

On this last figure, it is notable that 47% of Woonsocket’s residents were French speakers. Based on the fact that nearly half of all individuals living in Woonsocket at that time spoke French, six percent higher than the next highest city, it is not at all far-fetched to consider it the most French city in America.

The number of French-Canadians living in Woonsocket peaked at the time of the 1930 census, when 10,517 claimed to have been born in Canada.17 The wave of migration out of Quebec had ended shortly before this census was conducted, with the onset of the Great Depression in 1929. Although Woonsocket’s population continued to rise into 1940, the number of French-Canadians steadily declined, as manufacturing jobs vanished with the closing of many local mills.18

The French-Canadian heritage of the city of Woonsocket is still visible today. In the 2000 census, 46.1% of residents identified as having French-Canadian ancestry, although that number has been steadily decreasing. In 2010, when asked of their ancestry, 25.6% gave their first response as ‘French’ and 15.1% stated they had French-Canadian ancestry. In 2020, this number dropped to a combined 30% (16.1% stated French-Canadian, and 13.9% stated French).19 While the number of Quebec-born residents in Woonsocket has fallen over time, the legacy of these immigrants continues to live on.

Notes

1 Statewide Historic Preservation Report for Woonsocket, Rhode Island, RI Historic Preservation Commission, 1976, pg. 4.

2 Statewide Historic Preservation Report for Woonsocket, Rhode Island, RI Historic Preservation Commission, 1976, pg. 6.

3 Statewide Historic Preservation Report for Woonsocket, Rhode Island, RI Historic Preservation Commission, 1976, pg. 5.

4 Statewide Historic Preservation Report for Woonsocket, Rhode Island, RI Historic Preservation Commission, 1976, pg. 5.

5 Bélanger, Damien-Claude, French Canadian Emigration to the United States, 1840-1930, 1999, https://web.archive.org/web/20070125200529/http://www2.marianopolis.edu/quebechistory/readings/leaving.htm.

6 McLoughlin, William, Rhode Island, a History, (1986), pg. 186.

7 McLoughlin, William, Rhode Island, a History, (1986), pg. 186.

8 Richard, Sacha, "American Perspectives on La fièvre aux États-Unis, 1860–1930: A Historiographical Analysis of Recent Writings on the Franco-Americans in New England," Canadian Review of American Studies (2002).

9 1910 United States Federal Census, Ancestry.com.

10 1920 United States Federal Census, Ancestry.com.

11 “Chinese of the Eastern States” (L’Avenir Publishing Co., Manchester, NH, 1925), pg. 4.

12 “L’Union St. Jean Baptiste d’Amerique” Worcester Magazine, vol. 18, pg. 184.

13 Geddes, James Jr., “American-French Dialect Comparison,” Modern Language Notes, vol. 13, no. 1, 1898, pgs. 14-18.

14 US Newspaper Directory, Library of Congress, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/search/titles/results/?city=Woonsocket&rows=20&terms=&language=&lccn=&material_type=&year1=1690&year2=2023&labor=&county=Providence&state=Rhode+Island&frequency=ðnicity=&page=3&sort=relevance.

15 Society of American Baseball Researchers, Biography Project, Nap Lajoie, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/nap-lajoie/.

16 “French Towns in the United States” American Leader, vol. 4, pgs. 672-674.

17 1930 United States Federal Census, Ancestry.com.

18 1940 United States Federal Census, Ancestry.com.

19 United States Census Bureau Data from 2000, 2010, and 2020 censuses, https://data.census.gov/all?q=Woonsocket,+Rhode+Island+ancestry.

Share this:

About Zachary Garceau

Zachary J. Garceau is a former researcher at the New England Historic Genealogical Society. He joined the research staff after receiving a Master's degree in Historical Studies with a concentration in Public History from the University of Maryland-Baltimore County and a B.A. in history from the University of Rhode Island. He was a member of the Research Services team from 2014 to 2018, and now works as a technical writer. Zachary also works as a freelance writer, specializing in Rhode Island history, sports history, and French Canadian genealogy.View all posts by Zachary Garceau →