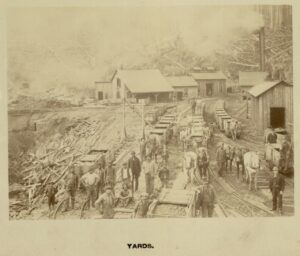

The yards at Beaver Hill mines. Courtesy of Yale University's Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

The yards at Beaver Hill mines. Courtesy of Yale University's Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Last fall I was asked to do some research for a local historical society called Oregon Black Pioneers about a group of coal miners recruited to work in Coos County, Oregon, at the end of the nineteenth century. The project was entirely open-ended, so I decided to present it in two main sections: an organized compendium of newspaper articles about the Black miners at Beaver Hill, Oregon, and an attempt to trace the history and descendants of every Black miner in Coos County who appeared in the 1900 census.

First, a little background is in order. Oregon was the only free state admitted to the Union (on 14 February 1859) with a constitution that excluded Black people from living in the state unless they had arrived prior to the constitution’s adoption in November 1857. This followed other Black exclusion laws during the territorial period, including the 1844 “lash law” that specified:

Section 6. That if any such free negro or mulatto shall fail to quit the country as required by this act, he or she may be arrested upon a warrant issued by some justice of the peace, and if guilty upon trial before such justice, shall receive upon his or her bare back not less than twenty, nor more than thirty-nine stripes, to be inflicted by the constable of the proper county.

The lash law was repealed (unused) the same year it was enacted, and the constitution’s exclusion provision was never actually enforced … though it was also not repealed until 1926. Nevertheless, the welcome mat was clearly never rolled out for Black settlers, and this legacy is still seen in the state’s modern demographics. According to the 2010 census, less than 2% of Oregonians identified as Black/African American.

In 1890, the state’s Black population stood at 1,186. In 1900 it had declined slightly to 1,105. Between those dates, the tiny coal mining community of Beaver Hill near the Pacific Ocean had been home to hundreds of Black miners and family members. They were recruited from states throughout the country, many coming through the coal mining towns of Black Diamond, Franklin, and Roslyn in the territory of Washington (which became a state 11 November 1899).

The mines at Beaver Hill closed early in 1898, and reopened in 1900 shortly after the census was taken. Beaver Hill village did not report any Black residents in the census that year, but there were thirty-one Black residents listed in the county. Two Black households lived in the town of North Marshfield (modern day North Bend): a bootblack named William Green and a barber named George W. Roberts, plus his wife, married daughter, and two grandchildren.

At the nearby Newport mines in the town of Libby, there were five single Black coal miners and three Black coal-mining families: the Trollingers, the McDonalds, and the Taylors. Several of the Trollingers eventually moved to San Francisco, some moved to the Seattle area, and one died in Salem and is buried in a cemetery a couple of blocks from me. He is included on a memorial to all the Black persons buried there, erected by Oregon Black Pioneers (the organization I did the research for). The McDonalds moved to Des Moines, Iowa, where they died a few decades later. The Taylor family settled in Everett, Washington; they moved into a brand-new house around 1907—where they lived through the 1940s—which still stands today.

Four other Black men were listed as day laborers for the railroad on Coos River. Initially I discounted them as miners … until my research uncovered that the Beaver Hill mines were owned by the same folks as the Coos Bay, Roseburg & Eastern Railroad. Sure enough, I was able to find evidence that three of the four had worked as miners in Washington, including the very last one I researched: Preston Jeter.

Preston Jeter was born in Richmond, Virginia sometime in the 1870s (records indicate various possible years); he died 25 June 1943 in Seattle. He married Clarice Lawson in Seattle on 20 May 1914, and they went on to have seven children. Their youngest daughter, Lucille, married a native of Vancouver, British Columbia named James Allen Ross “Al” Hendrix on 31 March 1942 in Seattle. Within days, Al was sent overseas to fight in World War II, and later in the year their first child was born. Initially Lucille named their son Johnny Allen Hendrix, but her husband later changed the boy’s name to James Marshall Hendrix. To the world he was known as Jimi. The rock guitar legend died 18 September 1970 in the Kensington district of London, and is buried with his father and step-mother in a grand memorial pavilion in Renton, Washington. Other members of the Jeter family are buried nearby.

You never know what you’re going to find when you start poking around!

Share this:

About Pamela Athearn Filbert

Pamela Athearn Filbert was born in Berkeley, California, but considers herself a “native Oregonian born in exile,” since her maternal great-great-grandparents arrived via the Oregon Trail, and she herself moved to Oregon well before her second birthday. She met her husband (an actual native Oregonian whose parents lived two blocks from hers in Berkeley) in London, England. She holds a B.A. from the University of Oregon, and has worked as a newsletter and book editor in New York City and Salem, Oregon; she was most recently the college and career program coordinator at her local high school.View all posts by Pamela Athearn Filbert →