I do a lot of lectures, courses, and online webinars about immigration, with my favorite period concentrating on the 1882 to 1924 period. This isn’t so much because of the improvement of the passenger lists, but more as a result of the many changes to the immigration laws in this period that began to limit what was considered an “acceptable” immigrant. Physical limitations, inability to get a job, and certain “loathsome and contagious” diseases were just some of the reasons an immigrant could have traveled all the way from their old country to America only to find that they wouldn’t be admitted.

I do a lot of lectures, courses, and online webinars about immigration, with my favorite period concentrating on the 1882 to 1924 period. This isn’t so much because of the improvement of the passenger lists, but more as a result of the many changes to the immigration laws in this period that began to limit what was considered an “acceptable” immigrant. Physical limitations, inability to get a job, and certain “loathsome and contagious” diseases were just some of the reasons an immigrant could have traveled all the way from their old country to America only to find that they wouldn’t be admitted.

I have always felt bad when working in case files about those who were deported or held up and filled with great uncertainty, but after my recent travels, I have even more empathy for those who found the door to America not as easy to get through as they thought.

I was fortunate three years ago to be approved by the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee (USOPC) as a journalist for the 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympics. You see, when I am not working hard at American Ancestors and New England Historic Genealogical Society with the Research Services and Library Department or giving lectures for the Education Department, I cover ice hockey from the collegiate level to the NHL to international teams. I had traveled to PyeongChang, Korea for the 2018 Winter Olympics, and now I was planning on going to Tokyo to cover water polo — which to me seems a lot like hockey in a pool.

Of course, COVID-19 gave us all a slap in the face and locked us down for 2020, and the Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympics were rescheduled for the same time in July-August 2021. Little did we know that by summer of 2021 there would be a delta variant of COVID-19, and once again the Olympics were in jeopardy.

In the end it was determined that they would take place, but with a lot of extra safety protocols in place. First, fans from outside Japan would not be allowed to travel and attend the games. That meant that for all the teams other than Japan, the only people allowed would be the athletes, coaches, trainers, other support staff, photographers, journalists, television crews, and other media. Protocols to deal with all of these individuals began to take form.

Protocols to deal with all of these individuals began to take form.

I spent time filling out a 14-day Activity Plan showing the venues I intended to visit. The government of Japan also insisted on a number of other things, including an app where I was to record my health each day, a portal where I would upload that activity plan, manage the health records, and keep track of other things related to COVID. I was also supplied with a special form that had to be filled out by an “accepted” medical organization to whom I would need to get two COVID tests (taken 96 hours and 72 hours prior to the takeoff time of my flight to Japan).

We heard that a decision was made that even those living in Japan would not be allowed to attend any of the sporting events as fans. So, all the games would be played without fans watching, with only media around to record what was happening. And in addition to all the paperwork, the online portal and the health app, there was also an app to track my whereabouts to assist Japan in contact tracing to help them in alerting anyone who came in contact with someone who tested positive for COVID during the Olympics. Yes, my GPS had to remain on the entire time I was in the country, so they knew where I was at all times. And I had a 50-count box of masks to take (some in my suitcases and some in my carryon).

As it got closer to my travel date, things weren’t coming together as expected. The portal wasn’t talking to the health app. The 14-day Activity plan hadn’t yet been approved. And per the instructions from the Japanese government, if that wasn’t approved then I wasn’t allowed into the country. Eventually, as I got within five days of flying, the easiest step turned out to be getting my two COVID tests and having the the testers fill out the paperwork for me.

Emails were coming in hot and heavy from the USOPC, the COVID group in Japan, and others, all saying get on the plane and things would be dealt with upon arrival. So, I did.

Then there was a QR code that I had to scan in Detroit ... and another form I had to fill out before I was allowed on the plane to Japan.

Well, first there was the showing of my negative COVID tests, my Olympic credential, a few other documents, and my passport to the nice woman at the check-in desk for Delta in Boston. Then there was a QR code that I had to scan in Detroit (where I changed planes) and another form I had to fill out before I was allowed on the plane to Japan.

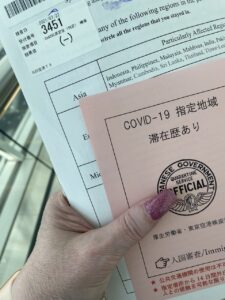

Once on the plane to Japan I was handed additional forms to fill out. One was the traditional Customs declaration, but the others all had to do with COVID-19 protocols. I admit to wondering if COVID-19 would have been called a “loathsome and contagious” disease. Probably.

After a 14-hour plane flight, a person met the plane and took the media individuals first (someone else took athletes after); we now went on a hike. If Ellis Island had the 6-second exam, watching the immigrants carry luggage, follow directions, and walk upstairs, Tokyo had the 20-minute walk to isolate us from anyone else in the airport. While I didn’t have steamer trunks, I did have a small bag and a rather large purse (with my computer and iPad in it). Thank goodness the small bag had wheels, or I never would have made it.

Because my health app wasn’t working, I was delayed, sitting in some seats and watching volunteers in isolation garb help people move on to the next point. It was here that I began to truly worry that I might not get into the country. My health app wasn’t working. My activity plan hadn’t been approved yet. All I had going for me were two negative COVID tests.

Because my health app wasn’t working, I was delayed, sitting in some seats and watching volunteers in isolation garb help people move on to the next point. It was here that I began to truly worry that I might not get into the country. My health app wasn’t working. My activity plan hadn’t been approved yet. All I had going for me were two negative COVID tests.

Eventually after getting a special paper with another QR code, and an admonition to get that health app working and logged on, I was given a paper with the word Quarantine on it and sent on to the next check point. There I had to take another COVID-19 test — this time a saliva test. They also looked at a health form I filled out on the plane and had to investigate the couple of medications I routinely take. After turning in my saliva test, I was taken to a holding area to await the results of the test. What would I do if it showed I was positive?

Fortunately, I did not have to handle that question as it tested negative. It was at this point that I was finally permitted to the checkpoint that would activate my Olympic Credential and from there it was to the immigration officials who did indeed let me into Japan.

Fortunately, I did not have to handle that question as it tested negative. It was at this point that I was finally permitted to the checkpoint that would activate my Olympic Credential and from there it was to the immigration officials who did indeed let me into Japan.

It took roughly three hours from touch down to walking through the sliding doors to pick up my luggage, and there were a few times that I felt the great uncertainty that our ancestors must have experienced going through immigration stations such as Ellis Island. Of course, at least at Ellis Island there were translators for the different languages. Communicating with many of the individuals throughout my arrival at Haneda Airport was difficult (and handled via Google Translate).

Share this:

About Rhonda McClure

Rhonda R. McClure, Senior Genealogist, is a nationally recognized professional genealogist and lecturer. Before joining American Ancestors in 2006, she ran her own genealogical business for 18 years. She was a contributing editor for Heritage Quest Magazine, Biography magazine and was a contributor to The History Channel Magazine and American History Magazine. In addition to numerous articles, she is the author of twelve books including the award-winning The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Online Genealogy, Finding your Famous and Infamous Ancestors and Digitizing Your Family History. She is the editor of the 6th edition of the Genealogist’s Handbook for New England Research, available in our bookstore. When she isn’t researching and writing about family history, she spends her time writing about ice hockey, covering collegiate to NHL teams and a couple of international teams. Her work has allowed her the privilege of attending and covering the 2018 Winter Olympics in PyeongChang, Korea and the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, Japan. Areas of expertise: Immigration and naturalization, late 19th and early 20th century urban research, missionaries (primarily in association with the American Board of Commissioners of Foreign Missions), State Department Federal records, New England, Mid-West, Southern, German, Italian, Scottish, Irish, French Canadian, and New Brunswick research as well as Internet research, genealogical software and online trees (FTM, RootsMagic, Reunion, AncesTrees, etc.), digital peripherals, and uses both Mac and Windows machines.View all posts by Rhonda McClure →