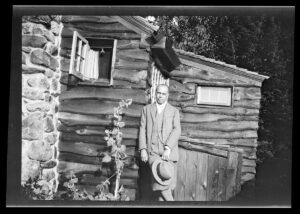

James Weldon Johnson at his writing cabin in western Massachusetts. Courtesy Yale Beinecke Library James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection

James Weldon Johnson at his writing cabin in western Massachusetts. Courtesy Yale Beinecke Library James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection

In 2000, I was asked to co-produce the James Weldon Johnson Medal ceremony under the guidance and leadership of the late Dr. Sondra Kathryn Wilson at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, New York. My wife, Jill Rosenberg Jones – the other producer – was my intended wife during that summer of 2000, and she was passionate about James Weldon Johnson – and because I intended to marry her, I thought it made sense for me to be passionate about James Weldon Johnson, too. Fast forward to June 2016, when we established the James Weldon Johnson Foundation to honor Johnson’s life through historic preservation and educational, intellectual, and artistic works that reflect the contemporary world and exemplify his enduring contributions to American history and worldwide culture.

James Weldon Johnson (1871-1938) was an author, professor, lawyer, diplomat, poet, songwriter, and civil rights activist; he remains a pivotal figure in American history and culture. In January 1900, he wrote the lyrics to Lift Every Voice and Sing for a celebration of President Abraham Lincoln’s ninety-first birthday. The song was put to music by his brother J. Rosamond Johnson (1873-1954), and it was first performed on February 12, 1900, by five hundred school children in Jacksonville, Florida. This would not be the only time Johnson’s work was to be associated with a president of the United States, as former Motown singer Kim Weston performed the song in January 2001 for President George W. Bush’s inauguration. In 2009 and again in 2013, President Barack Obama recited and sang Lift Every Voice and Sing as part of the inaugural celebrations. Most recently, in January, for the inauguration of President Joseph Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris, the world listened to Johnson’s lyrics being recited as excerpts of Lift Every Voice and Sing were read during the Gift Giving Ceremony in the Capitol Rotunda.

On behalf of the Joint Congressional Committee on The Inauguration of Joseph R. Biden, Jr., Congressman Steny Hoyer said the following: “Mr. President in your speech you talked about faith. You talked about tribulations, but you talked about victory. The Johnson Brothers wrote a great hymn. You know it well, Mr. President. Today, we have a new day. That hymn came out of faith and out of deep trouble into hope. And they said, ‘Facing the rising sun of our new day begun/Let us march on till victory is won.’ That's what your speech was about. And that's why we are so proud and ready to march with you, President Biden. God bless.”

From the mouths of presidents to the ears of people in church pews, classrooms, and homes: the range and standard of the literature and art that James Weldon Johnson produced underline his greatness as an American...

From the mouths of presidents to the ears of people in church pews, classrooms, and homes: the range and standard of the literature and art that James Weldon Johnson produced underline his greatness as an American; however, Johnson is today an under-recognized yet pivotal figure in American history. The James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection at Yale’s Beinecke Library and Emory’s Woodruff Library together hold approximately 1,500 manuscripts and artifacts from Johnson’s life. These institutions document and celebrate his cultural and artistic achievements, and it is the role of the James Weldon Johnson Foundation to supplement those collections.

Johnson and his wife Grace Nail Johnson (1885-1976) did not have children. Proper estate planning allowed Mrs. Johnson to make decisions about the handling of her husband’s creative works and to provide additional ownership information for his books, music, and other copyrighted material. Each person who in turn inherited the James Weldon Johnson Literary Estate didn’t have children, but each one passed along the family history and valuable artifacts, documents, letters, books, and items dating back over 120 years as stewards, managing and caring for the estate.

James Weldon Johnson was the first African-American to be admitted to the Bar in the State of Florida (in 1898), and he was careful in his record-keeping, tracing the progression of ownership. Grace Nail Johnson kept up with all the copyrights because she was so passionate about ensuring her husband’s legacy. At her death, she passed on the literary estate to Ollie Jewel Ocala. Ms. Ocala didn't have children and bequeathed the Johnson estate to Johnson scholar Dr. Sondra Kathryn Wilson. Dr. Wilson brought all of Johnson’s books back into print, extending all the possibilities associated with his legacy. Sondra did not have children and bequeathed the literary rights of the estate to my wife, Jill.

Jill’s mother met Sondra at Columbia University; they became best friends while completing their doctorates. In due course, when Jill was a teenager, she was the obvious person to carry on the James Weldon Johnson legacy. As I’ve mentioned, she passed that passion on to me.

One night, very late, Sondra whispered in Jill’s ear: “James Weldon Johnson, Great Barrington.”

It might seem strange, but Jill being named executor of the James Weldon Johnson Literary Estate is completely separate from us buying a property in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, where the Johnsons had long lived. In 2011, several months after Sondra’s death, my wife – a New Yorker looking for “green” places – was researching “country homes.” One night, very late, Sondra whispered in Jill’s ear: “James Weldon Johnson, Great Barrington.” Jill awoke and typed those five words into her browser, and up popped “African American Leader's Home for Sale.” It was Johnson’s former summer home, “Five Acres,” with its writing cabin, still intact on the hill above the brook, and hidden by a hemlock grove, the remnant of the original forest. The realtor also felt strongly about the historic value of the property and was thrilled to sell it to our family, because we were dedicated to preserving this part of Johnson’s legacy.

What the realtor didn’t know until the closing was that Jill had had the dream and we wanted to own the real estate where Johnson wrote two of his notable works (utilizing the Town of Great Barrington’s Mason Library for the purpose). While living at Five Acres, Johnson completed and published a book of seven sermons called God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse (1927) as well as his autobiography Along This Way (1934).

It pleases us – as I am sure it would please the Johnsons and Sondra – that we happened “along this way,” combining Jill’s work managing the Johnson Estate with mine at the foundation even as we live at Five Acres, the site of some important events in the lives of James Weldon Johnson and Grace Nail Johnson.

*

I will be delivering a virtual lecture at 7:00 PM EST on Friday, February 5, with a question-and-answer session to follow. The lecture is being presented by the Community Development Corporation of South Berkshire in celebration of Black History Month. It is free and reservations are required to access the Zoom webinar link. To reserve a spot, email allison@cdcsb.org.

Share this:

About Rufus Jones

Rufus E. Jones Jr. is the co-founder and president of the James Weldon Johnson Foundation, which preserves “Five Acres,” the summer home of James Weldon Johnson and Grace Nail Johnson in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, and promotes educational, intellectual, and artistic works that reflect Johnson’s enduring contributions to American history and worldwide culture. A professional musician, singer/songwriter, recording artist, and bandleader in New Jersey and Massachusetts, Rufus is a native of Memphis, Tennessee, and holds a B.A. degree from Harvard University and an M.B.A. from the University of Tennessee.View all posts by Rufus Jones →