Baseball is back! As someone who has always loved baseball, I could not be more excited to see the players return to the diamond. Although the game might not look exactly like it did last year, these differences simply remind us of how baseball has changed over the years, and how it will continue to do so in the future.

Growing up in eastern Connecticut, an allegiance to the Boston Red Sox has deep roots in my family. In fact, many of them still talk about that fateful Game 4 in 2004, when the curse of the Bambino was broken for good.[1] Personally, baseball has always meant something special to my father’s family. As my paternal grandfather died long before I was born, he was always the biggest question mark on my family tree. Before I began doing research of my own, the only fact I knew about my grandfather was that he played in the Negro Baseball Leagues.

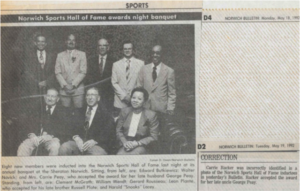

It was not until recent research that I discovered that George Peay, my grandfather, was born on 18 May 1927 in Kershaw County, South Carolina.[2] George moved north to New London County, Connecticut, married my grandmother, and began playing baseball. He joined a Negro League in Norwich, Connecticut, and played for a number of years. On 17 May 1992, George was posthumously inducted into the Norwich Sports Hall of Fame for his time playing in the Negro Leagues.[3]

While trying to learn more about my grandfather’s baseball career, I hit countless roadblocks. As I quickly discovered, researching Negro Baseball Leagues can be quite a challenge. The league’s lack of initial recognition combined with minimal records means finding answers typically will not be as easy as a quick search. Nevertheless, there are a number of organizations and authors who are researching, cataloguing, and sharing their finds to help make exploring the Negro Leagues more manageable for people like me.

There are also museums available for both research and general knowledge, the most notable being the Baseball Hall of Fame and the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

In terms of authors, Robert W. Peterson’s Only the Ball was White: A History of Legendary Black Players and All-Black Professional Teams[4] helped kick start a movement to delve into the complex history of Black professional baseball. Countless authors have continued to shed light on this topic, including men such as Kadir Nelson, whose illustrated work titled We Are the Ship: The Story of Negro League Baseball,[5] strives to make baseball’s complicated past accessible to children. There are also museums available for both research and general knowledge, the most notable being the Baseball Hall of Fame and the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. Both have plenty of resources, although the Negro League museum does not currently have a research facility.[6]

For genealogical research, organizations like the Society for American Baseball Research have made it their mission to help provide more tools to researchers. On their website devoted to researching the Negro Leagues, the Society has listed a number of sources and links for people who want to take a deeper look at the subject. They also provide tips and suggestions for different resources and how to use them to get the most out of your search. For anyone who wants to get into researching the Negro Leagues, this is the perfect place to start.[7]

I personally was only able to find mentions of my grandfather’s baseball career in the local newspaper. While many newspapers are beginning to upload their records to accessible databases, there are plenty who have yet to upload their entire collection (or even in part). This happened in my quest for uncovering more about my grandfather. Unfortunately, the Norwich Bulletin only has a select number of years catalogued so far, and the restrictions from Covid-19 limited access to the microfilms stored at the local library.

I personally was only able to find mentions of my grandfather’s baseball career in the local newspaper. While many newspapers are beginning to upload their records to accessible databases, there are plenty who have yet to upload their entire collection (or even in part). This happened in my quest for uncovering more about my grandfather. Unfortunately, the Norwich Bulletin only has a select number of years catalogued so far, and the restrictions from Covid-19 limited access to the microfilms stored at the local library.

Thankfully, I was able to make some calls to a few family members who uncovered the article pertaining to his induction in 1992. While newspapers are some of the best records to search for mentions of the Negro Leagues, there are quite a few obstacles that can also make them a challenging primary resource. Adding to the challenge of limited access to newspapers online, many of the games played in the Negro Leagues were only recorded in the local newspapers. Therefore, if a team was playing an away game, it probably written about in the town paper of the away team and was not mentioned in the team’s hometown.[8] There are countless challenges awaiting those who want to research their family history in the Negro Leagues, but if it isn’t hard, is it really worth it?

I still have plenty more research to do of my own, but in the meantime, I plan to watch some baseball. So, as Fenway and baseball parks across America slowly begin to reopen and baseball resumes once more, it is important to remember the names of those players who have helped forge America’s pastime as we see it now. Personally, I’ll be thinking of the members of my family who brought me to my first Red Sox game and the grandfather I never knew, but who loved the game just as much as me.

Notes

[1] A reference to the superstition that the Red Sox were cursed after trading Babe Ruth (the Bambino) to the New York Yankees in 1919. After the trade, the Sox went 86 years without winning the World Series.

[2] U.S. WWII Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947 [database on-line].

[3] Norwich Bulletin (Norwich, Conn.), 18 May 1992. The paper listed Mrs. Carrie Peay as the one who accepted the award for her late husband. After seeing the article, Carrie had a correction printed the next day. She was actually Carrie Rucker and was accepting the award for her late uncle.

[4] Robert W. Peterson, Only the Ball was White: A History of Legendary Black Players and All-Black Professional Teams (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992).

[5] Kadir Nelson, We Are the Ship: The Story of Negro League Baseball (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 2008).

[6] The Baseball Hall of Fame is located in Cooperstown, N.Y., and the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum is in Kansas City, Mo.

[7] Society for the American Baseball League, “Researching the Negro Leagues.”

[8] Ibid.

Share this:

.jpg)

About Elizabeth Peay

Elizabeth works as a genealogist for the Publishing team, writing for the Newbury Street Press. Using extensive research and advanced scholarship, she compiles and produces family history projects to meet the highest scholarly standards. One of Elizabeth’s most notable works is the three volume Biographies of Original Members and Qualifying Officers: Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Connecticut. Throughout her work, Elizabeth stays in contact with the Advancement team in order to ensure a strong line of communication with her clients. She also works with the Education department to create and deliver lectures, some of which have focused on colonial New England genealogy and Revolutionary War genealogy. Elizabeth has also contributed to the Vita Brevis blog. Prior to her work with American Ancestors, Elizabeth studied at the University of Connecticut and Smith College, earning a dual BA in History and Classical Studies. She completed an internship for the Tiffany Windows Education Center in Boston and worked for Historic New England at Roseland Cottage. Elizabeth’s areas of expertise include colonial New England, the French and Indian War, the Revolutionary War, Land Bounty records, and Pension records.View all posts by Elizabeth Peay →