Just the other day I received an email from a friend in Provincetown. It started out cheerily enough with him telling me of an exhilarating walk he had taken at Great Island in Wellfleet, but it struck a despairing note at the end when he mentioned that a recent New York Times story about Mayflower 400 events had failed to even mention Provincetown. Unfortunately, when it comes to the Pilgrim story, Provincetown is accustomed to being overlooked.

Growing up summers in Provincetown during the 1970s, I remember many of the old-time Yankees expressing their frustration that Plymouth, not Provincetown, was getting all the credit as the First Landing Place of the Mayflower Pilgrims. I seem to recall a small dust up in late 1970, the year of the 350th Pilgrim Landing anniversary, when a new Postal Service Pilgrim stamp (six cents in those days!) had its first-day issue in Plymouth. If memory serves me, there was a follow up event in Provincetown, but the wind had already been taken out of Provincetown’s sails. The folks in Provincetown weren’t happy, though they certainly didn’t want a cold war with their friends across the Bay.

Publicly, Provincetown versus Plymouth was a good-natured rivalry and made for an innocent kind of sensationalism in the newspapers, but privately Provincetowners were frustrated that they hadn’t been accorded their rightful place in the popular imagination or in the history books. The frustration was two-pronged: not only did accounts mistakenly credit Plymouth as the first landing place of the Pilgrims, but Provincetown never received so much as a mention in the telling of the story. Oh, well. Playing second fiddle had been going on long before my time, though one wonders what more could have been done to change hearts and minds. Had Plymouth and its iconic rock simply done a better job of marketing their Pilgrim story?

The frustration was two-pronged: not only did accounts mistakenly credit Plymouth as the first landing place of the Pilgrims, but Provincetown never received so much as a mention in the telling of the story.

Looking at Provincetown’s publicity efforts, the town had, in fact, always been quite proactive in tooting its own horn, enthusiastically celebrating the significant anniversaries with community events and scattering the landscape with monumental reminders for the thousands of modern-day pilgrims who, every summer, landed on her shore. Since many of the streets had been named for Mayflower passengers – one of the two main thoroughfares is named Bradford Street – visitors were reminded of the town’s history at every turn. As early as 1891, the town had adopted as its official seal a scrolled parchment noting that the Mayflower Compact had been signed while the Mayflower was anchored in Provincetown Harbor on 11 November 1620 and that Provincetown was the “Birthplace of American Liberty.” There was also the tradition of the town crier, begun by George Washington Readey (1833-1920) in the late 1880s. Though Readey went about town in street clothes, later criers rang their bell and recited the news of the day in Pilgrim costume.

In 1892, a group of Mayflower descendants formed the Cape Cod Pilgrim Memorial Association with the purpose of building a monument to commemorate the first landing of the Pilgrims on Cape Cod. It was to be an “admirable landmark” that could be seen “from every town on Cape Cod and could be seen by every vessel in any reasonably fair weather coming in or going out of Massachusetts Bay.”[1]

In 1907, with President Theodore Roosevelt in attendance, the cornerstone was laid – with great fanfare – for the Pilgrim Monument. Three years later, rising 252 feet atop High Pole Hill and inspired by the Torre del Mangia in Siena, Italy, it was dedicated – with equal fanfare – in the presence of President William Howard Taft. It wasn’t long before the “admirable landmark” became Cape Cod’s most recognized landmark. (In 1962 the historical museum opened on the grounds.) Surely, reasoned the town fathers, there would no longer be confusion about where the Pilgrims had landed or Provincetown’s place in history.

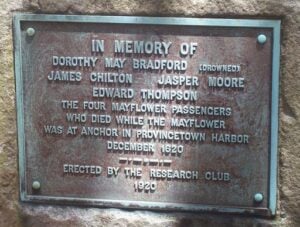

Just a short decade later in 1920, Provincetown pulled out all the stops for its Pilgrim Tercentenary, the cover of its official program unabashedly proclaiming, “The Nation was Founded Here.” In the years leading up to the grand affair, much discussion had been taking place about the installation of permanent memorials to commemorate Pilgrim history. For the tercentenary, the Ladies Research Club, founded in 1910, dedicated a tablet in the town’s oldest cemetery (see above) in memory of the four Mayflower passengers – Dorothy (May) Bradford, James Chilton, Jasper Moore, and Edward Thompson – who had died while the Mayflower was at anchor in Provincetown Harbor. Three years earlier, in 1917, club members had installed a tablet, mounted on a rock, at the spot in the West End where, after their long voyage, the Mayflower passengers had come ashore for the first Wash Day.

Plans for another sculpture, The Pilgrim Mother, honoring the contributions of women in founding the nation, were never realized...

For the tercentenary, a magnificent bronze bas-relief, Signing of the Compact, created by sculptor Cyrus Dallin, was unveiled on a landscaped park in the center of town at the base of High Pole Hill in the shadow of the Pilgrim Monument which, that year, welcomed 16,000 visitors (and 22,000 in 1921).[2] Plans for another sculpture, The Pilgrim Mother, honoring the contributions of women in founding the nation, were never realized, but historic locations in Truro, Wellfleet, and Eastham highlighting the five-week exploration of the outer Cape by the Pilgrims were appropriately marked. It seemed that Provincetown and its First Landing Place status was beginning to permeate the collective consciousness.

The marketing campaign quieted down for a while until, in the 1940s, a bohemian character named Harry Kemp (1883-1960), the “Poet of the Dunes,” began taking it upon himself to promote the underappreciated Provincetown Pilgrim story, though not without ruffling a few feathers along the way by referring to Plymouth Rock as a hoax! As chairman of a new association, Provincetown Pilgrims Association, Kemp was an early advocate for a full-size Mayflower replica that would be anchored permanently in Provincetown Harbor, and a Pilgrim village, enclosed within a stockade out in the dunes, where hardy “Pilgrims” might live. (Interestingly, Kemp spent much of his life living in a shack in those same dunes.) He endeavored too, to organize an annual swim from Provincetown to Plymouth, retracing the Pilgrim route. With few participants able to swim the lengthy course, the so-called American Channel Swim never got off the beach, but from Provincetown’s beach Kemp began sending samples of sand to dignitaries nationwide to represent the first terra firma trod on by the Pilgrims in the New World. “Not on Plymouth Rock but on Provincetown Sand/The Pilgrim Fathers first came to land.”

Beginning in 1947, during the Thanksgiving week, members of Kemp’s association, dressed in Pilgrim costume, annually reenacted the First Landing of the Pilgrims, rowing ashore from a fishing boat. On the tidal flats in the West End they knelt, prayed, and recreated the First Wash Day. Kemp’s pageant became an annual tradition and attracted considerable media attention. Sadly, with his passing in 1960 the reenactment survived only one more year. It had always been Kemp’s dream, too, to immortalize Wash Day in sculpture, though that project, like The Pilgrim Mother sculpture, was never realized.

Voices that had urged the building of a Mayflower replica had also urged a “rebuilding of the whole Provincetown Pilgrim picture.” A 1955 editorial in the Provincetown Advocate, “The Fault, Dear Brutus,” addressed the community’s concerns and protestations that Provincetown had been omitted from the original itinerary of the Mayflower II’s sail from England. (The itinerary was revised and the Mayflower II did follow the historic course, visiting Provincetown.) “It must be admitted,” noted the writer, “that Plymouth has done a superb job.” The writer went on to remark, “Plymouth children are brought up, educated and, to an extent, trained in an atmosphere of their town’s history.” What special training, asked the writer, “if any, is given to Cape End youngsters in the lore of their own locale?”

Displays of civic pride, including a Pilgrim Costume Ball and a Wash Day reenactment by schoolchildren, marked the 350th anniversary in 1970, though the postage stamp controversy as well as the refusal by Plymouth to send the Mayflower II to Provincetown for a reenactment of the signing of the Mayflower Compact frustrated anniversary organizers, some of whom reluctantly travelled to Plymouth for the signing.

In 1995, the year of the 375th anniversary of the Pilgrims’ first landing, Provincetown residents revived Harry Kemp’s traditional pageant on the tidal flats of the West End and rededicated First Landing Park overlooking those flats and the moors.

Work had first begun on the Park project in 1947 (coincidentally at the same time that Plymouth was creating its living history museum, Plimoth Plantation), a project overseen by Selectman Ralph Carpenter, “a committee of one” appointed by the selectmen. A descendant of Mayflower passengers Peter Brown and John Alden through his mother, Lydia Etta Snow, his father Edmund J. Carpenter (1845-1924) had served as secretary of the Cape Cod Pilgrim Memorial Association during construction of the Monument and had written a book, The Pilgrims and their monument, published in 1911.

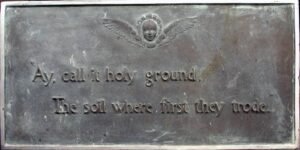

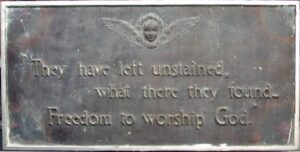

Ralph Carpenter, the unofficial “Town Custodian of Historical Markers,” secured private funding for First Landing Park, some of which came from an account his father had opened to provide a set of chimes (never realized) to accompany the Monument atop High Pole Hill. When First Landing Park was dedicated in late 1948, the bronze tablet originally dedicated in 1917 by the Ladies Research Club – then relegated to the overgrown brush across the street – became the centerpiece of a flagstone and brick plaza surrounded by a wrought iron fence. Mounted on piers at each side of the tablet were bronze plaques fashioned by master sculptor William Boogar.

Ralph Carpenter, the unofficial “Town Custodian of Historical Markers,” secured private funding for First Landing Park, some of which came from an account his father had opened to provide a set of chimes (never realized) to accompany the Monument atop High Pole Hill. When First Landing Park was dedicated in late 1948, the bronze tablet originally dedicated in 1917 by the Ladies Research Club – then relegated to the overgrown brush across the street – became the centerpiece of a flagstone and brick plaza surrounded by a wrought iron fence. Mounted on piers at each side of the tablet were bronze plaques fashioned by master sculptor William Boogar.

A distinguished member of the Provincetown art colony, as well as an esteemed member of the artists’ fraternity known as the Beachcombers (as was Ralph Carpenter), Boogar had been approached by Carpenter to design the bronzes for the plaza. The last stanza of a poem by Felicia Dorothea Browne Hemans, “The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers in New England,” was inscribed on the plaques.

A distinguished member of the Provincetown art colony, as well as an esteemed member of the artists’ fraternity known as the Beachcombers (as was Ralph Carpenter), Boogar had been approached by Carpenter to design the bronzes for the plaza. The last stanza of a poem by Felicia Dorothea Browne Hemans, “The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers in New England,” was inscribed on the plaques.

Felicia Hemans (1793-1835), a Liverpool-born poetess, had enjoyed a popular following in the United States. The story goes that in 1825 she purchased two volumes at a book store that were wrapped in pages of an address delivered at Plymouth to commemorate Forefathers’ Day, the landing of the Pilgrims at Plymouth. (Another version of the story says that her groceries were wrapped in the pages.) Moved by the address, in a flash of inspiration she wrote her poem, the original title of which was “The Breaking Waves Dashed High.” The poem became a centerpiece of poetry literature for schoolchildren well into the twentieth century.[3]

The Provincetown Advocate described the poem as having “started New World history off with the right foot on the wrong spot.” If Felicia Hemans had, in her poem, unwittingly misrepresented “where they first trod” as having been Plymouth, perhaps the use of the stanza on the plaques at Provincetown was a deliberate word play to set the record straight. It seems unlikely that the town, after all its efforts (and disappointments) over the years, would knowingly reinforce the so-called Plymouth hoax.

Boogar’s plaques, beautifully crafted with a tell-tale “style” that any Boogar devotee recognizes, and their plaza remained in place overlooking Provincetown Harbor and its salt marsh until 1955, when the plaza was removed to make way for a traffic rotary, inside of which was the new First Landing Park. While the 1917 Ladies Research Club tablet found a home in the park, the William Boogar plaques disappeared. (In another aside, First Landing Park is currently undergoing another redesign and sprucing up for the 400th anniversary.)

Mystery surrounds their whereabouts for the next half century, but in 2010 they were “discovered” on display, in plain view, in the front yard of a Provincetown residence. The gentleman who discovered the plaques was writing a book about the built environment of Provincetown and recognized the plaques immediately as being the missing Boogar artwork. Now in the possession of the Pilgrim Monument and Provincetown Museum, discussions are underway to reinstall the plaques in a public place where they can again be appreciated and serve as yet another reminder of Provincetown’s place in Pilgrim history.

In these difficult times, when so many of the long-planned Mayflower 400 events may have to be postponed or cancelled, we can take heart that the landscape first trod by the Pilgrims will still be there when we all emerge from confinement. The story of the Pilgrims’ monumental achievement is written on that landscape from Provincetown to Eastham. In time, we’ll again climb High Pole Hill, visit the Pilgrim Monument, and look out to the bay, picturing in our mind a small vessel and its passengers, battered and weary, turning the corner at Long Point and finding refuge in Provincetown Harbor. The days ahead were not without uncertainty, but together the Pilgrims shared the promise of a fresh start and the hope for a better future.

Notes

[1] Cape Cod Pilgrim Memorial Association fundraising booklet, 1904. Town of Provincetown municipal archives.

[2] The Signing of the Compact has recently been restored to its original splendor in preparation for the 400th anniversary. The park is also being re-landscaped.

[3] The original manuscript is in the Pilgrim Hall Museum collection.

Share this:

About Amy Whorf McGuiggan

Amy Whorf McGuiggan recently published Finding Emma: My Search For the Family My Grandfather Never Knew; she is also the author of My Provincetown: Memories of a Cape Cod Childhood; Christmas in New England; and Take Me Out to the Ball Game: The Story of the Sensational Baseball Song. Past projects have included curating, researching, and writing the exhibition Forgotten Port: Provincetown’s Whaling Heritage (for the Pilgrim Monument and Provincetown Museum) and Albert Edel: Moments in Time, Pictures of Place (for the Provincetown Art Association and Museum).View all posts by Amy Whorf McGuiggan →