The coronavirus crisis has inspired me to think of past health heroes. My paternal grandmother, Anne P. (Cassidy) Dwyer (1892–1964) of Fall River, Massachusetts, immediately comes to mind. As a first-generation American, daughter of an Irish widow, Anne overcame adversity through drive and determination. She worked ten years in the cotton mills to put her brother through school before she enrolled at St. Joseph’s Hospital School of Nursing in Providence. When she graduated in the spring of 1917, the United States had entered World War I. Some of her classmates volunteered for service in France, but Anne’s mother vigorously dissuaded her from going. One of those nurses, Henrietta Drummond of Pawtucket, perished in a mustard gas attack.[1]

For the next few years, Anne worked in Providence as a district nurse, carrying her trademark bag throughout the city to deliver babies and to care for families during epidemics. I have often wondered how many lives she saved and how many children did she brought safely into the world.

One story vividly attests to Anne’s life-saving intervention. Eleanor Clynes Edgett (1918–1997), Anne’s only niece, recounted this incident. Two little girls, Eleanor and Elizabeth Farland – then in second grade – shared an apple during recess. By noon, they were sent home with a fever and difficulty in breathing. Eleanor’s mother made a frantic call to Providence. My grandmother rushed home on the train to Fall River, and immediately recognized Eleanor’s symptoms of diphtheria. Anne intubated the child, thereby saving her life. Elizabeth, on the other hand, without the same skilled medical attention, died that evening.

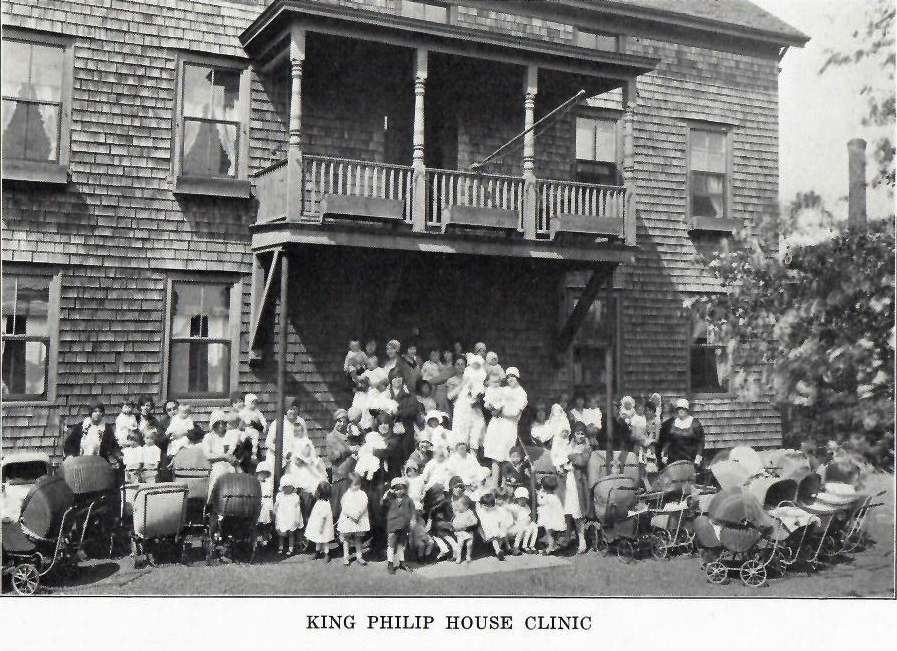

That brush with death prompted Anne to leave Providence and to join the Fall River District Nursing Association, formed a decade earlier. Among the treasures from my grandmother’s house, a much-thumbed booklet, the association’s annual report for 1930, gives some telling details of why their work was critical: At the height of the textile mill boom in 1912 when Fall River’s population swelled to 120,000, the city experienced a death rate of 155 per thousand births, “one of the highest mortality rates in the country.” The public outcry resulted in more nurses joining the association. In addition to their home visits, they also founded the King Philip Settlement House Clinic. By 1930, their efforts showed significant results – the death rate fell to 66 per thousand births.

Anne’s picture in uniform appeared for the last time in this report because she had married the year before, at the age of 37.

Anne’s picture in uniform appeared for the last time in this report because she had married the year before, at the age of 37.

Her wedding to my grandfather, Michael F. Dwyer, made the Fall River Herald News with the headline, “District Nurse Becomes Bride.” Few of the district nurses of that era married, and nearly all of them enjoyed long and productive careers. My grandmother kept her friendships with the district nurses for the rest of her life. I remember their bridge parties – always with tempting plates of petits fours!

If my grandmother were living today, she would fully understand the power of a pandemic and how quarantine was sometimes the only way to stem contagion. Let us remember, now and then, the skill of health professionals who make all the difference.

Note

[1] For more on these nurses, see Michael F. Dwyer, “Student Nurses of St. Joseph’s Hospital, 1915,” Rhode Island Roots 36 [2010]: 100–2.

Share this:

About Michael Dwyer

Michael F. Dwyer first joined NEHGS on a student membership. A Fellow of the American Society of Genealogists, he writes a bimonthly column on Lost Names in Vermont—French Canadian names that have been changed. His articles have been published in the Register, American Ancestors, The American Genealogist, The Maine Genealogist, and Rhode Island Roots, among others. The Vermont Department of Education's 2004 Teacher of the Year, Michael retired in June 2018 after 35 years of teaching subjects he loves—English and history.View all posts by Michael Dwyer →