The other night I tuned into one of my favorite programs, the always interesting and informative American Experience. I’ve been a devotee for most of the 30 years that the series has been produced. Taken as a whole, the series reminds me of one of those exquisite, perfectly-put-together album quilts of yesteryear, made by many hands, each block of eye-catching fabric elaborately designed, intricately sewn, and an expression and remembrance of the world as it was.

The episode I watched was one I had viewed when it first aired a year or two ago, “The Race Underground,” about Boston overcoming a plethora of challenges to build America’s first subway system. By the late nineteenth century, Boston’s traffic was so snarled, so congested (sounds familiar!), that it was impeding progress. Not only were there more than 400,000 people stuffed into the downtown, but 8,000 horses were pulling the trollies, moving intra-city freight (the word teamster, now meaning a truck driver, originally described the driver of a team of draft animals), providing private travel and emergency services, and serving as a source of energy (the word horsepower relates to the power of draft horses compared to a steam engine) for construction and harbor development projects. Indispensable to nineteenth- and early twentieth-century urban life, horses were viewed not as living creatures but as machines. Overworked and mistreated, urban life took its toll.

Christmas for the Horses became as much a Boston tradition as hanging a wreath or selecting a tree.

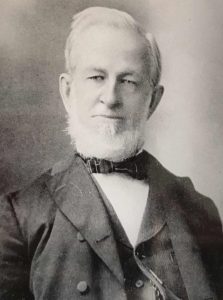

As I watched the episode, my thoughts drifted off to a holiday event that I had written about some years ago, an event held in Boston beginning in 1916 and continuing until the mid-1950s. Christmas for the Horses became as much a Boston tradition as hanging a wreath or selecting a tree. Its goal was to enlist public interest in the plight of working horses who, for too long, had trod Boston’s streets exhausted, sick, lame, frightened, and abused. The event would never have taken place but for the earlier efforts of George Thorndike Angell, a lawyer and humanitarian who founded the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in 1868.

Born in Southbridge, Massachusetts on 5 June 1823, George Thorndike Angell was the son of the Rev. George Angell (1785–1827) and Rebekah Thorndike (1789–1869). His paternal and maternal ancestries read like a who’s who of Great Migration families. Thomas Angell (c. 1616–1694) is said to have arrived in New England, as a minor, with or at about the same time as Roger Williams (c. 1631); he was an early settler, with Williams, of the Providence Plantation after Williams’ expulsion from the Massachusetts Bay Colony. In his Great Migration Directory, Robert Charles Anderson includes an entry for Thomas Angell, of unknown English origin, arriving at Providence in 1637.[1] If the first footing of the Angell family in America is a little murky, the ancestral line to George Thorndike Angell is a bit clearer: from Thomas, to John, Hope, Abiah, Benjamin, and George Angell, the father of George Thorndike Angell.[2]

Born in Southbridge, Massachusetts on 5 June 1823, George Thorndike Angell was the son of the Rev. George Angell (1785–1827) and Rebekah Thorndike (1789–1869). His paternal and maternal ancestries read like a who’s who of Great Migration families. Thomas Angell (c. 1616–1694) is said to have arrived in New England, as a minor, with or at about the same time as Roger Williams (c. 1631); he was an early settler, with Williams, of the Providence Plantation after Williams’ expulsion from the Massachusetts Bay Colony. In his Great Migration Directory, Robert Charles Anderson includes an entry for Thomas Angell, of unknown English origin, arriving at Providence in 1637.[1] If the first footing of the Angell family in America is a little murky, the ancestral line to George Thorndike Angell is a bit clearer: from Thomas, to John, Hope, Abiah, Benjamin, and George Angell, the father of George Thorndike Angell.[2]

George Thorndike Angell’s maternal Thorndike line benefits from a sketch by Mr. Anderson.[3] John Thorndike (1611–1668), having arrived from Lincolnshire in 1632, lived in Ipswich[4] and Salem before returning to England, where he died, in 1668. Married to Elizabeth Stratton, seven children – six daughters and one son, Paul – were born to the couple. From Paul, the Thorndike line descends to John, James, Paul, and Rebekah, the mother of George Thorndike Angell.

The Rev. George Angell was born in Smithfield, Rhode Island in 1785. Said to have been an infidel in his youth, a grave illness helped him down an eventual path of Divine grace. In 1809 he was baptized and admitted to the First Baptist Church in Providence. In November 1810, he married Lydia Farnum, the granddaughter of Rev. Samuel Windsor, and in 1813 he was ordained. The couple moved to Southbridge where, in 1816, Rev. George Angell began his ministry. Within two years he was bereaved of his son, daughter, and his wife. [5]

In 1819, Rev. George Angell married Worcester schoolteacher Rebekah Thorndike, one of ten children born to Lt. Paul Thorndike and his wife, Olive Fletcher of Tewksbury. One child, George Thorndike Angell, was born to the couple. In 1827, when George was only four years old, Rebekah was widowed. The family’s circumstances required her to continue teaching and young George to enter employment at a dry goods shop. After two years his mother placed him in an academy in New Hampshire to prepare him for college, subsequently enrolling first at Brown University and then Dartmouth College. He later attended Harvard Law School and was admitted to the bar in 1851.

In an autobiographical sketch, George Thorndike Angell recollected that he had always been “extremely fond of animals, – dogs, horses, cats, cattle, sheep, birds, all these and many others. I had seen, and personally interfered in, a number of cases of cruelty to them, and had heard of many others. I did not know that there was a thing in the world as a ‘society for the prevention of cruelty to animals,’ – the nearest being in London, Eng., – but I thought something should be done for their protection.”[6]

A letter from Angell to the Boston Daily Advertiser, in which he protested the cruelty, caught the attention of Boston’s most distinguished and influential citizens, who rallied around the cause.

It was the cruelty of a “great horse-race” on 22 February 1868 – “in which two of the best horses of the State were driven from Brighton to Worcester, about forty miles, over rough roads, each drawing two men, and both were driven to death” – that convinced Angell, then a forty-five year-old Boston lawyer, of the need to educate people, especially children, “in the ways of kindness.” A letter from Angell to the Boston Daily Advertiser, in which he protested the cruelty, caught the attention of Boston’s most distinguished and influential citizens, who rallied around the cause. On 23 March 1868, an Act to Incorporate the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals was submitted to the Massachusetts General Court. It was the second society of its kind in the country.[7]

George Thorndike Angell became, as one newspaper noted, “perhaps the most conspicuous fighter for the rights of dumb beasts that the world has ever known.” Humane education became his life’s work. “A thousand years of prosecution,” he wrote, “would find the human race no better than now. Fifty years of humane education may substantially abolish wars, and crimes of violence, and cruelty to both animals and men, and usher in the dawn of peace on earth and good-will to every living creature.”

When he died on 16 March 1909 – survived by his wife Eliza – newspapers across the country mourned his passing. The horses had lost their angel. By the thousands they came, wearing mourning rosettes in their bridles and filling the streets of Boston on the day of his funeral to participate in the cortège.

In 1912, Boston schoolchildren began collecting pennies for the construction of the Angell Memorial Fountain in Post Office Square, a site chosen for its proximity to the main arteries of equine traffic. It was there, on the afternoon of Christmas Eve in 1916, that the first Christmas for the Horses was celebrated.

Upon the fountain a Christmas tree stood tall, colorfully festooned with Yuletide cheer, with carrots, apples, bells, tinsel, garland, and pennants printed with the words “BE KIND TO ANIMALS” and “BLANKET THE HORSE.” Throughout the day, thousands of spectators viewed the tree and welcomed the more than one thousand guests – carriage, police, and draft horses – who were treated to a sumptuous meal of oats, apples, carrots, and corn.

Francis Rowley, George Thorndike Angell’s successor as MSPCA president, remarked that “It is not so much the benefit to the horses as it is a reminder to the people of the worth and faithfulness of the dumb animals. It does the horses good, of course, but they do not remember the food; it is only a meal to them. But the real value of this is to bring home to people the idea of caring for the animals.”

How pleased George Thorndike Angell would be to know that more than one hundred fifty years after he became a voice for those who cannot speak, his influence is wide and his good work continues. As one writer noted, “such lives are not lived in vain.”

Merry Christmas to all God’s creatures.

Notes

[1] Robert Charles Anderson, The Great Migration Directory: Immigrants to New England 1620-1640 (Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2015), 8.

[2] J.H. Beers & Co., Representative Men and Old Families of Rhode Island (Chicago: J.H. Beers & Co., 1908), 1216.

[3] Robert Charles Anderson, The Great Migration Begins: Immigrants to New England 1620-1633, 3 vols. (Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1995), 3: 1811.

[4] Anderson notes that “Mr. Thornedicke” was among the nine men who were permitted to accompany John Winthrop Jr. in settling Ipswich.

[5] William B. Sprague, D.D., Annals of the American Baptist Pulpit (New York: Robert Carter & Brothers, 1860), 599–601.

[6] George Thorndike Angell, Autobiographical Sketches and Personal Recollections (Boston: The American Humane Education Society, 1883), 7.

[7] Ibid., 8–12.

Share this:

About Amy Whorf McGuiggan

Amy Whorf McGuiggan recently published Finding Emma: My Search For the Family My Grandfather Never Knew; she is also the author of My Provincetown: Memories of a Cape Cod Childhood; Christmas in New England; and Take Me Out to the Ball Game: The Story of the Sensational Baseball Song. Past projects have included curating, researching, and writing the exhibition Forgotten Port: Provincetown’s Whaling Heritage (for the Pilgrim Monument and Provincetown Museum) and Albert Edel: Moments in Time, Pictures of Place (for the Provincetown Art Association and Museum).View all posts by Amy Whorf McGuiggan →