The Stamp Act, passed in 1765 by the British Parliament, was a levied tax on legal documents, almanacs, and newspapers – basically, any form of paper used in the American colonies. The reason Britain passed the Stamp Act was to pay for the British troops stationed in North America, there to “protect” the colonists.

The Stamp Act, passed in 1765 by the British Parliament, was a levied tax on legal documents, almanacs, and newspapers – basically, any form of paper used in the American colonies. The reason Britain passed the Stamp Act was to pay for the British troops stationed in North America, there to “protect” the colonists.

The tax was to be paid in the British form of money, sterling, not the paper money the colonists used. This was the first direct tax that Parliament had used on the colonists. (The Sugar Act, passed in 1764, was a tax on trade rather than a tax on the everyday life of the colonists.) The colonists took to the streets to push for the Act's repeal. Mob violence occurred, spreading throughout the colonies, causing stamp distributors to resign to avoid enforcing the act. Since the colonists had no say in the British Parliament, the slogan “no taxation without representation” became a common phrase throughout the 1760s, and is still in use today.

“[No] taxation without representation” became a common phrase throughout the 1760s...

At first Parliament made it clear that because Great Britain had dominion over the colonies, the colonists had to obey the tax. The colonists’ intense dislike of the Act and their protests spurred the creation of the Stamp Act Congress, a group of Colonial activists who sent petitions to London denying the right of taxation to Parliament on behalf of the colonists.

In 1766, Parliament repealed the Stamp Act. This was due in part to British merchants’ concerns, as the colonists boycotted goods coming from England. Britain had relied heavily on trade with the Americas. The Stamp Act cemented a new era of colonial relationships with Britain. It unified the colonies and stimulated a sense of unease and unrest against authority in England.

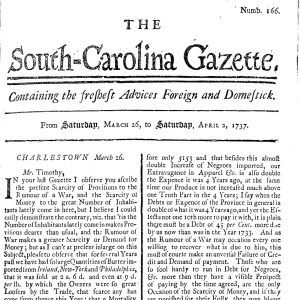

Eighteenth-century newspapers became an important tool for affecting change and spreading the word, reaching both local communities and the greater colonies. (Today, in the form of newspaper databases, they help us to understand trade, life, and death in early America, aiding us in Research Services as we seek to illuminate our clients' family histories.)

The South Carolina Gazette, started in 1732, was a paper published in Charleston. Before the Stamp Act was passed, its articles and letters came from other colonies’ newspapers as well as London newspapers. Once the Stamp Act was implemented, the paper began to speak more to the people of South Carolina. A sense of community grew. Contributors spoke to their “brethren,” asking for them to band together against the Motherland and boycott British goods.

He is showing allegiance to the community he lives in and his American countrymen...

A letter, written by George Saxby, published in the 31 October 1765 issue of the Gazette, is a bold statement of contempt for the Stamp Act. Saxby was one of the stamp distributors appointed by Parliament for Charleston. He states that neither he nor the other distributor, Caleb Lloyd, will distribute or execute the Stamp Act. He is showing allegiance to the community he lives in and his American countrymen rather than to the foreign Parliament.

One reason for the South Carolina Gazette’s stand was the fact that for nine months in 1766 it nearly ceased publication, as the publisher could not pay the tax. A small notice stating that the Gazette could not afford the required paper to publish in full filled a single sheet for many of the 1766 issues. The South Carolina Gazette was one of many newspapers throughout the colonies directly affected by the Stamp Act, creating a hole in information during that time period for the colonists as well as for today’s historians and genealogists.

Once the Act was repealed, the paper was finally able to go back to publishing, yet they were behind on the times. For the moment, the Gazette mostly published stories that had already run in other colonial newspapers. Yet the stories that ran used wording that would begin to form the outline of the American Constitution. Words like liberty, freedom, our property, and our rights began to articulate a sense that change was needed and beginning to occur. The colonists believed that though the Act was repealed, their issues with Britain were not over. Though not stated outright in any of the articles, the idea of Revolution was beginning to simmer.

Share this:

About Mollie Braen

A graduate of the University of Denver, including a semester at the University of Glasgow in Scotland, Mollie majored in Art History and minored in Marketing and History; she plans to continue her education with an MBA in Non-Profit Management. Mollie performs administrative work for Research Services, supporting the researchers in ordering microfilm, managing correspondence with constituents, and organizing research materials. In her free time, Mollie, who recently moved to Boston from Los Angeles, enjoys travelling. With a family home on Lake Sebago in Maine, she often travels there as well as other parts of New England.View all posts by Mollie Braen →