Boulevard du Temple, Paris. The solitary man having his shoes shined is at lower left. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

Boulevard du Temple, Paris. The solitary man having his shoes shined is at lower left. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

Perhaps more than any other event, the introduction of photography altered how individuals were memorialized and are remembered. While portraits have been produced for thousands of years, photographic images were first introduced about 1838 and the first known photograph to contain people was produced between April and May of that year.[1] This photograph is of the Boulevard du Temple in Paris, and due to the long exposure time of about ten to twelve minutes, all people in the photograph moved and avoided being captured in the image, with the exception of a man having his shoes shined who remained still for the length of the exposure.[2]

The first publicly known photographic process was known as daguerreotypy, named after its founder, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre.[3] This process involved taking a highly polished plate of silver (often a layer of silver on top of a plate of a copper substrate), and coating it with halogen fumes. The plate was then exposed to an image through a lens for a period of time ranging from a few seconds to several minutes, depending upon the chemicals used.[4] Lastly, the image was developed by exposing the plate to mercury fumes for several minutes, causing the image to appear.[5]

The process of creating Daguerreotypes revolutionized the world of portraiture and was met with excitement in America almost immediately. The announcement of the creation of daguerreotypy was first published in American newspapers in February 1839.[6] The first daguerreotype studio was opened in New York in 1841 and an article published in The Pittsburgh Gazette on 3 May 1841 claims “Daguerreotype portraits have given so much satisfaction to the lovers of fine arts in the city.”[7]

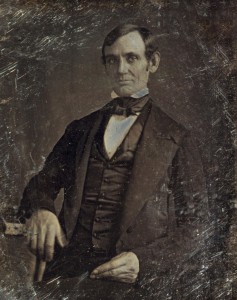

The earliest authenticated image of Abraham Lincoln, taken by Nicholas H. Shepard of Springfield, Illinois, in 1846. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The earliest authenticated image of Abraham Lincoln, taken by Nicholas H. Shepard of Springfield, Illinois, in 1846. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

For the first time, Americans could share personal images of themselves with their loved ones without being a part of the upper classes. But “daguerreotype fever,” as the movement became known, was not confined to the United States and Europe. The first known Australian daguerreotype was taken in 1841.[8] In Japan, the first known photograph, a portrait of Shimazu Nariakira, was taken in 1857.[9] The growth in popularity of daguerreotypes was aided by the reduction of exposure time, a development which began in the early 1840s with the creation of new lenses and modifications to the processes used.[10] Owing to the lack of electric lights during the first half of the nineteenth century, many photography studios were constructed on the roofs of buildings with glass walls and ceilings to utilize as much of the natural light as possible.[11]

The introduction of photography was not only used for capturing everyday life, but also came to be used to document the Civil War. The most well-known images of the war were produced by Mathew Brady, who first opened a photography studio in New York City in the 1850s and quickly became the nation’s preeminent photographer.[12] Brady photographed battlefields, camps, towns, and people during the War. He was not able, however, to photograph battles, as the technology of the era still required subjects to be still for the duration of the photograph.[13] Brady’s work, The Dead at Antietam, opened to the public in his New York studio in October 1862, and for the first time civilians were able to see the results of the war.[14] According to Megan Kate Nelson’s Ruin Nation, Brady’s work was “meant to create as complete a record of war as possible to accumulate ‘the materials of history.’"[15]

After the War, Brady opened a studio in Washington, D.C., where he took the portraits of many prominent citizens and politicians, providing historians with accurate images of many of the era’s most powerful individuals.[16] With introduction of photography during the 1840s, individuals worldwide were able to have a portrait taken for far less money than ever before, and for this reason images of our ancestors can be found in family albums, town collections, and historic archives, allowing historians, family researchers, and descendants to see the way people appeared in periods long since passed.

Notes

[1] Sylvia Ballhause, Sylvia, “The Munich Daguerre-Triptych,” sylviaballhause.de.

[2] Ibid.

[3] National Portrait Gallery, “Portrait Photography: From the Victorians to the Present Day,” Teachers’ Resource, p. 8.

[4] N. G. Burgess, “Amusing Incidents in the Life of a Daguerrean Artist,” The Photographic and Fine Art Journal 8 [1855]: 190.

[5] Ibid.

[6] “Chemical and Optical Discovery,” The Pittsburgh Gazette, 28 February 1839, p. 2.

[7] “Daguerreotype Portraits at Washington,” The Pittsburgh Gazette, 3 May 1841, p. 2.

[8] This image no longer survives; therefore, the oldest surviving Australian photograph is a portrait of Dr. William Bland taken in 1845 (Allan Davies, “Photography in Australia,” Celebrating 100 Years of the Mitchell Library [Sydney: Focus Publishing, 2000], p. 76).

[9] Terry Bennett, Early Japanese Images (Clarendon, Vt.: Tuttle Publishing, 2013), p. 137.

[10] National Portrait Gallery, “Portrait Photography: From the Victorians to the Present Day,” p. 8.

[11] Burgess, “Amusing Incidents in the Life of a Daguerrean Artist,” 8 [1855]: 190.

[12] Megan Kate Nelson, Ruin Nation (Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press, 2012), p. 166.

[13] U.S. National Archives, “Teaching With Documents: The Civil War as Photographed by Mathew Brady”

[14] Nelson, Ruin Nation, p. 166.

[15] Ibid., p. 167.

[16] “Mathew Brady: Photographer,” CivilWar.Org.

Share this:

About Zachary Garceau

Zachary J. Garceau is a former researcher at the New England Historic Genealogical Society. He joined the research staff after receiving a Master's degree in Historical Studies with a concentration in Public History from the University of Maryland-Baltimore County and a B.A. in history from the University of Rhode Island. He was a member of the Research Services team from 2014 to 2018, and now works as a technical writer. Zachary also works as a freelance writer, specializing in Rhode Island history, sports history, and French Canadian genealogy.View all posts by Zachary Garceau →