As I write this, a few days before the New Year begins, Vita Brevis is nearly a year old; it has had more than 300,000 page views since its first post on 2 January 2014. (This is a statistic I like to trumpet, although of course a single reader on a given day might well look at more than one entry: so I cannot claim 300,000 unique readers over the course of the first year, much as I would like to!) That first post, Generatio longa, vita brevis, hinted at the blog’s purpose: “Vita Brevis will include short posts on research methods – applicable to a variety of genealogical subjects – as well as posts on results. Like a mosaic, these posts will, in time, form a new collection for the genealogical researcher to explore.”

During 2014, we occasionally broke news; more often, though, the blog’s authors wrote about their research interests and offered advice – and, sometimes, rueful suggestions about what not to do!

Back on 20 January, Penny Stratton urged readers to write what you know. After reviewing family stories that seemed almost too good to be true (and were), she noted: “As wonderful as these stories have been, their failure to hold up under standard methods of genealogical scrutiny makes me question other family lore I encounter. Yes, it’s wise to start with what you know, but perhaps we should reword that advice: start with what you know and can prove.”

Back on 20 January, Penny Stratton urged readers to write what you know. After reviewing family stories that seemed almost too good to be true (and were), she noted: “As wonderful as these stories have been, their failure to hold up under standard methods of genealogical scrutiny makes me question other family lore I encounter. Yes, it’s wise to start with what you know, but perhaps we should reword that advice: start with what you know and can prove.”

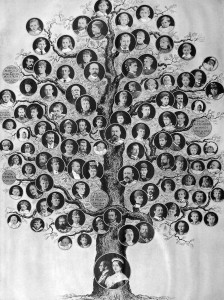

On 4 February, I wrote about a new library acquisition, an exuberant genealogical tree chart showing the family of Queen Victoria at the time of her Diamond Jubilee in 1897: “[The] longest-surviving member of the English Royal Family shown is Princess Alice of Albany, the daughter of Queen Victoria’s youngest son, Prince Leopold. Born at Windsor Castle in February 1883, she married King George V’s brother-in-law Prince Alexander of Teck [created Earl of Athlone in 1917]. Lord Athlone, … Governor General of South Africa and then Governor General of Canada, died in 1957; Princess Alice – the last surviving grandchild of Queen Victoria – died at Kensington Palace in January 1981, just shy of her 98th birthday.”

On 4 February, I wrote about a new library acquisition, an exuberant genealogical tree chart showing the family of Queen Victoria at the time of her Diamond Jubilee in 1897: “[The] longest-surviving member of the English Royal Family shown is Princess Alice of Albany, the daughter of Queen Victoria’s youngest son, Prince Leopold. Born at Windsor Castle in February 1883, she married King George V’s brother-in-law Prince Alexander of Teck [created Earl of Athlone in 1917]. Lord Athlone, … Governor General of South Africa and then Governor General of Canada, died in 1957; Princess Alice – the last surviving grandchild of Queen Victoria – died at Kensington Palace in January 1981, just shy of her 98th birthday.”

A few weeks later, on 21 March, Ryan Woods described his emotions on discovering – in a diary kept by his wife’s great-grandfather – that a member of his family had been present in the household on the day in 1909 when his grandmother-in-law was born: “A memorable day this morning at 2:40 our first daughter was born. We decided to call her Ruth Evelyn. Doctor went home about 4 o’clock. In the morning I telephoned to Mr. Whitcomb to let Mother Southworth and Father Douglass know the news. Jennie Woods [Ryan’s great-great-aunt] came to help with the housework until Mother Southworth should arrive. Mother came on the 4:45 train….”

On 17 April, Henry Hoff wrote about using heraldry in genealogical research: “I have had two good genealogical experiences with heraldry – and no bad ones.”

When I was developing the West Indian ancestry of my ancestress, Susanna (Heyliger) Bainbridge, I found that her grandson (my great-grandfather) had drawn up an elaborate [and bogus] coat of arms for her husband, Commodore William Bainbridge, based on the arms of an unrelated Bainbridge family…. Included in this heraldic disaster … were the supposed arms of the Heyliger family. And, as it turned out, they were valid arms — though not for the Heyliger family (!)

Five weeks later, Robert Charles Anderson sketched out the mental shift involved when the Massachusetts Bay Company became the Massachusetts Bay Colony. For early grandees like Sir Richard Saltonstall or Lord Saye and Sele, “top-down” development was preferable to “bottom-up,” but conflict between the two models was inevitable, as when, “In 1635, the [ship] Christian set forth for New England; most of its adult male passengers were carpenters hired by Sir Richard Saltonstall and bound for Connecticut. Their new settlement was meant to be erected on the same site already chosen by some newly arrived inhabitants who had come from Dorchester, Massachusetts. This contested spot would become the town of Windsor. Saltonstall’s carpenters and their families were allowed to remain, but Saltonstall’s personal colonization plans were frustrated.”

Five weeks later, Robert Charles Anderson sketched out the mental shift involved when the Massachusetts Bay Company became the Massachusetts Bay Colony. For early grandees like Sir Richard Saltonstall or Lord Saye and Sele, “top-down” development was preferable to “bottom-up,” but conflict between the two models was inevitable, as when, “In 1635, the [ship] Christian set forth for New England; most of its adult male passengers were carpenters hired by Sir Richard Saltonstall and bound for Connecticut. Their new settlement was meant to be erected on the same site already chosen by some newly arrived inhabitants who had come from Dorchester, Massachusetts. This contested spot would become the town of Windsor. Saltonstall’s carpenters and their families were allowed to remain, but Saltonstall’s personal colonization plans were frustrated.”

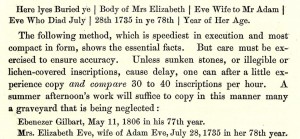

On 19 June, Helen Herzer highlighted the NEHGS Committee on Epitaphs, established in 1899. For many of us, vital information is often first found on gravestones in cemeteries, but even 115 years ago people were concerned about the steady loss of these stones from pollution and neglect. Soon after the committee was formed, a communiqué to members gently chided them for the slow pace of their work: “While everything on the stone is valuable, names, dates, statement of the social relation, mortuary verse, decorations, and even the stone cutter’s evident errors; yet the copying of everything, delightful and fascinating though it is, takes time, and for lack of time many stones remain uncopied and the inscriptions in danger of being lost through the destruction of the stones.”

On 19 June, Helen Herzer highlighted the NEHGS Committee on Epitaphs, established in 1899. For many of us, vital information is often first found on gravestones in cemeteries, but even 115 years ago people were concerned about the steady loss of these stones from pollution and neglect. Soon after the committee was formed, a communiqué to members gently chided them for the slow pace of their work: “While everything on the stone is valuable, names, dates, statement of the social relation, mortuary verse, decorations, and even the stone cutter’s evident errors; yet the copying of everything, delightful and fascinating though it is, takes time, and for lack of time many stones remain uncopied and the inscriptions in danger of being lost through the destruction of the stones.”

The list continues, and concludes, here.

Share this:

About Scott C. Steward

Scott C. Steward has been NEHGS’ Editor-in-Chief since 2013. He is the author, co-author, or editor of genealogies of the Ayer, Le Roy, Lowell, Saltonstall, Thorndike, and Winthrop families. His articles have appeared in The New England Historical and Genealogical Register, NEXUS, New England Ancestors, American Ancestors, and The Pennsylvania Genealogical Magazine, and he has written book reviews for the Register, The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, and the National Genealogical Society Quarterly.View all posts by Scott C. Steward →