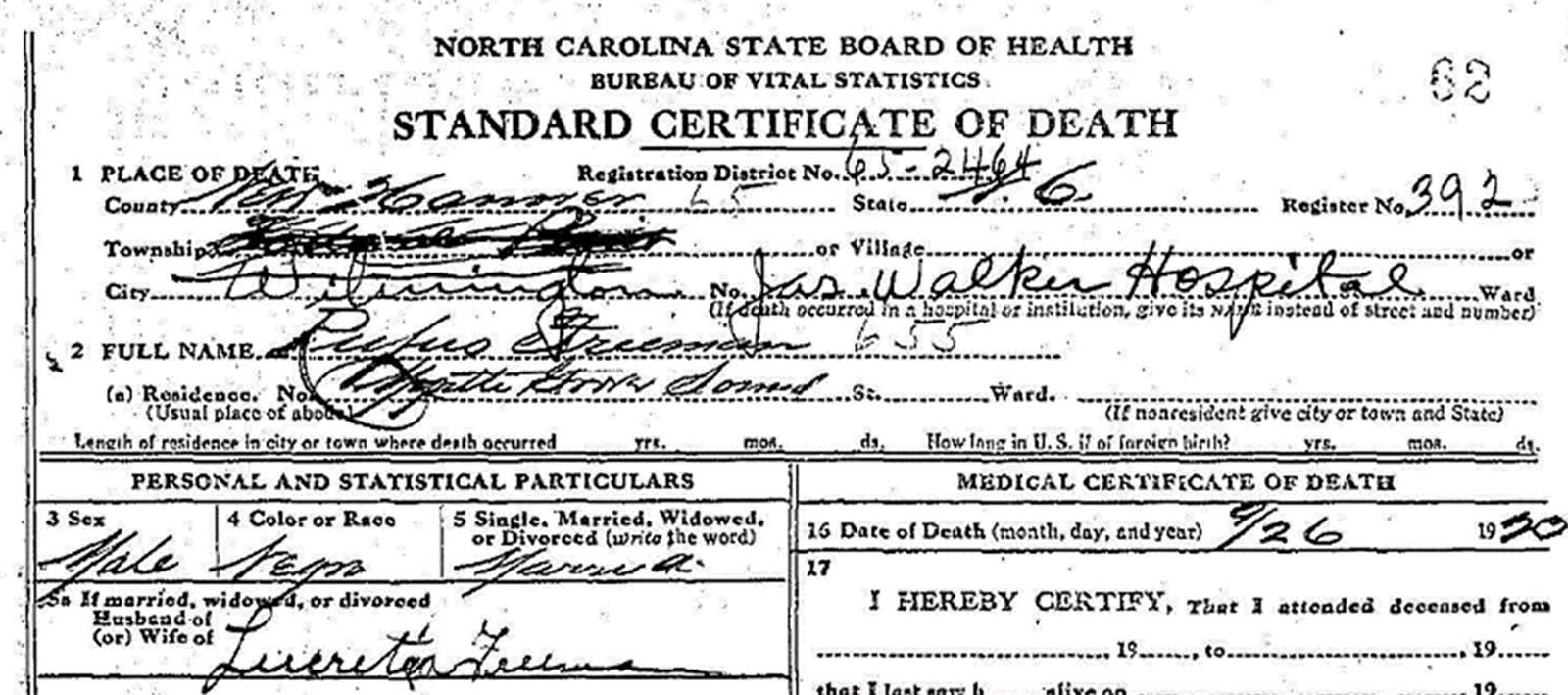

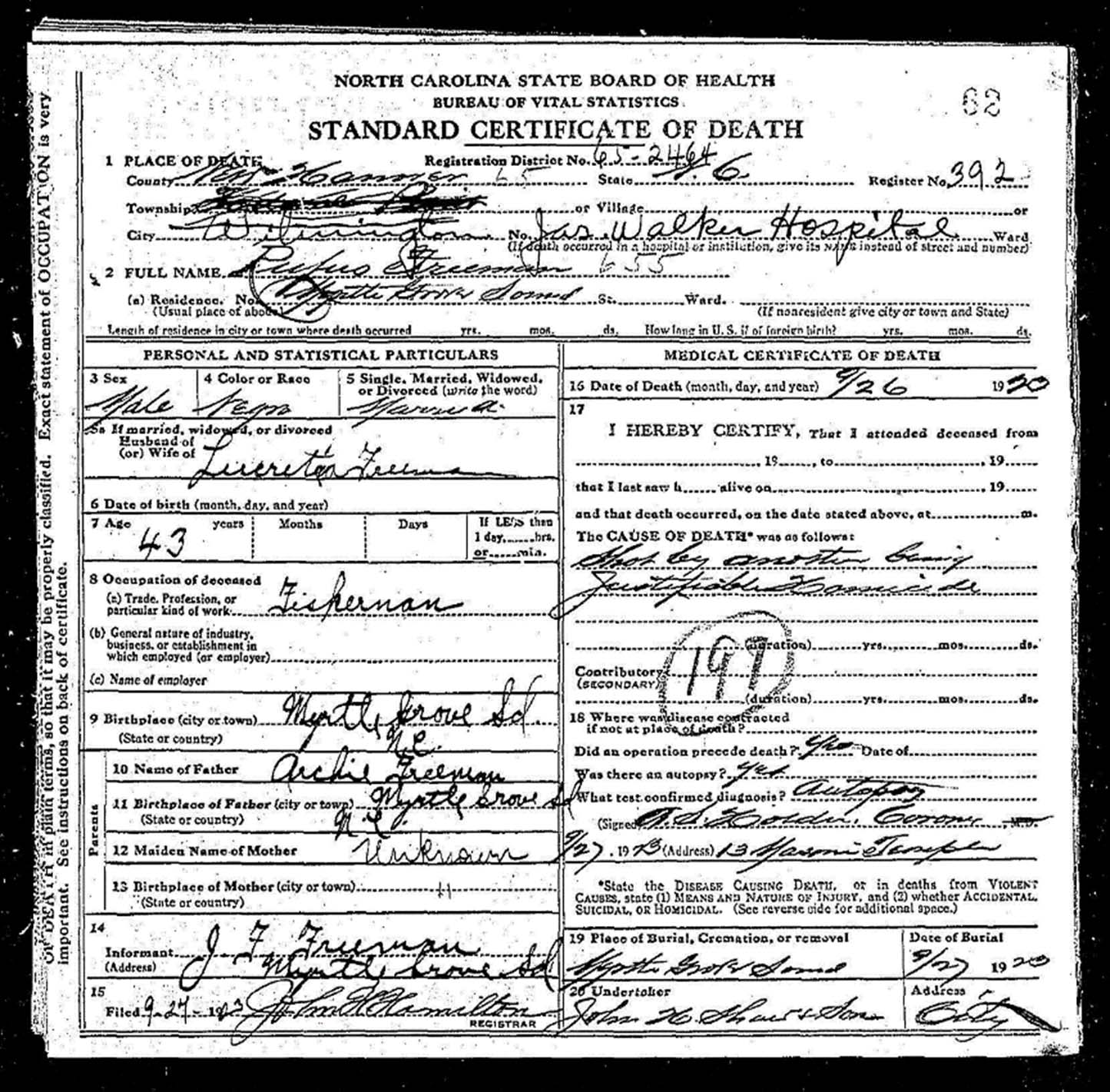

According to his death certificate, Rufus Freeman of Myrtle Grove Sound in New Hanover County, North Carolina died on 26 September, 1923. 1 An autopsy was done in James Walker Hospital by the coroner G. S. Holden, who confirmed Rufus Freeman’s cause of death: “shot by another, being justifiable homicide.”

It was the cause of death that grabbed my attention. Justifiable homicide is an extremely bold claim, especially considering the certificate was filed only the day after the murder. It is also not a claim which a coroner is qualified to make. That dubious honor would belong to judge and jury, assuming that charges were pressed against the unnamed murderer. To top it all off, Rufus Freeman was Black—and given that he was killed in North Carolina at the height of the Jim Crow era, I was skeptical that I would find any evidence of due process. I searched newspaper databases (Newspapers.com, GenealogyBank, and NewspaperArchive) for mentions of court proceedings regarding Rufus’s murder, and came up empty-handed.

It’s worth noting that the Freeman name has a special significance to the history of Myrtle Grove Sound. Between 1855 and 1872, 180 acres of land on this beach were purchased by Alexander Freeman and his wife, Charity. Alexander and Charity were free African Americans from North Carolina, and the land they purchased went to their children, who passed it on to their children in turn. 2 One of their descendants, Robert B. Freeman Sr., bought an additional 2500 acres of land on the water. The family went on to sell portions of the land they had amassed to other Black families.

By 1920, Freeman Beach was transformed into a thriving beachside community. At its peak between 1920 and 1950, the beach and the surrounding townships along Myrtle Grove Sound, most notably the resort town Seabreeze, became a haven for African Americans living under segregated Jim Crow South. Photographs held at the Federal Point Historic Preservation Society give the sense of a joyful and well-loved community.

Young crabbers in Seabreeze. Federal Point Historic Preservation Society.

So, was Rufus Freeman indeed a descendant of the people who built this community? And what were the real circumstances of his death? To find answers, I decided to go back to the basics: vital records and censuses.

The death certificate I had found revealed more about Rufus’s life and gave me some information to work with. He was a fisherman, the son of Archie Freeman, married to Lucretia Freeman, and 43 years old at time of death. His biographical information was provided by J.F. Freeman of Myrtle Grove Sound, possibly a brother or son.

Death Certificate of Rufus Freeman, 1923

Hoping to find a marriage certificate between Rufus and his wife, Lucretia, I uncovered two marriage records for Rufus Freeman of New Hanover County, North Carolina. In the first, he married Martha Lowe in 1902, and his parents were listed as R B Freeman and Florine Freeman.3 The 1910 federal census corroborated this: Rufus and Martha Freeman were recorded living in Federal Point Township, New Hannover, North Carolina with children Geneva, Osiola, and Marcellus.4

The second marriage record was from the year 1921, between Rufus Freeman and Theresa Brown.5 The listed parents were the same: Robert Freeman and Florine Freeman.

At first, I believed that the Rufus Freeman in these marriage records was an entirely separate individual. Neither of his wives’ names matched the name of his wife on the death certificate, and his father’s name was different as well. But Rufus is not the most common name, and Federal Point Township is adjacent to Myrtle Grove Sound—only 11 miles away, on the east side of Cape Fear River. To add to the pile of evidence, I found Theresa Freeman in the 1920 census, married to Rufus Freeman (though their marriage certificate was filed in 1921), and living in New Hanover County with Rufus and his 11 year old son, Marcus.6 She appears again in the 1930 census, this time listed as a widow in Wilmington, New Hanover County, North Carolina.7 Her age is consistent in both records. This was enough evidence for me to attest that the Lucretia named in Rufus Freeman’s death certificate was an error, and that his wife was in fact Theresa (Brown) Freeman.

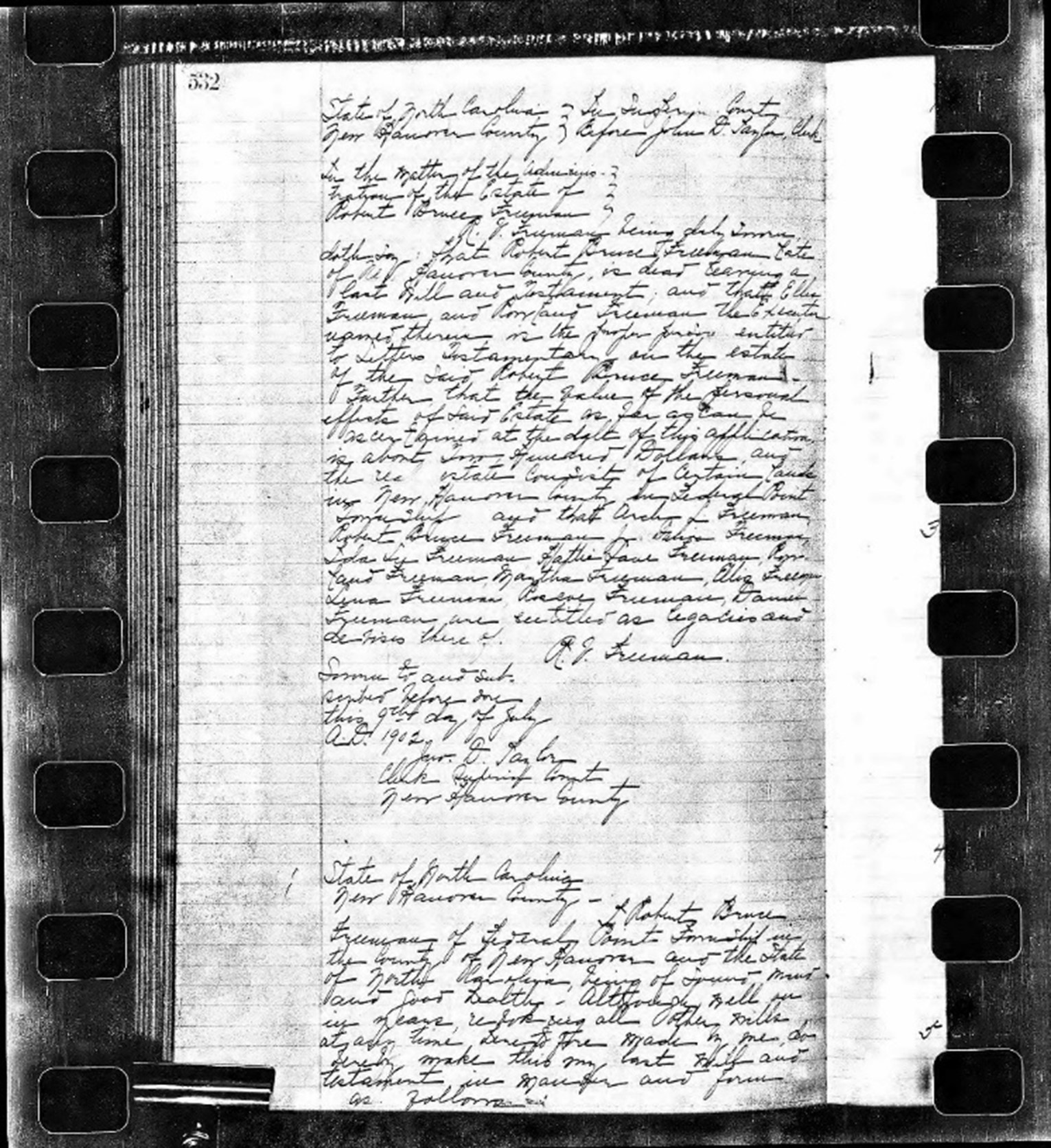

This also meant that Rufus’s father, “Archie”, was likely Robert B. Freeman of Myrtle Grove Sound, North Carolina. However, there actually was an Archie Freeman in Rufus’s family. His 1930 death record states he was born in Myrtle Grove Sound in 1858 to Robert B and Catherine Freeman,8 and the 1870 census shows him enumerated in the household of Robert Bruce “Brose” Freeman, along with his younger brother, Robert Bruce Freeman Jr.—the father of Rufus Freeman.9 Robert Bruce Sr.’s 1900 will names both Archie and Robert Jr., as well as several other children, as recipients of the land he amassed in his life.10

First page of the will of Robert Bruce Freeman, Sr., naming Archie and Robert Jr. From North Carolina U.S. Wills and Probate Records 1665-1998.

While Freeman Beach was a haven for the Black community, their joy must have been tempered by the circumstances of the time. As Andrew Kahrle writes in This Land Was Ours: How Black Beaches Became White Wealth in the Coastal South :

“[Robert] Freeman’s death came in the midst of a wave of racial terrorism sweeping across the state. Beginning in 1898, white supremacy campaigns laid waste to the state’s experiment in interracial democracy. In Wilmington, a racial pogrom resulted in the forced removal of black elected officials and the death of scores of black citizens, followed by the unsettling calm of Jim Crow segregation and black political disfranchisement.”11

Could the murder of Rufus Freeman have fallen into this pattern of racialized violence? Without more context, I cannot make that judgement. I do know, however, that there is no conceivable circumstance in which a homicide can be judged “justifiable” in the span of 24 hours. I have found no evidence of any newspaper or court attempting to bring justice to Rufus Freeman and his family. While I still do not know the circumstances of Rufus Freeman’s murder, I hope that additional research can shed light on this tragedy.

The story of the Freeman family of Myrtle Grove Sound is far from over. In 2021, a dispute two decades in the making between descendants of the Robert Freeman and the Town of Carolina Beach came to a close. The subject of the dispute was Freeman Park, the area comprising the original 180 acres bought by Alexander Freeman. The park was still owned by Freeman’s descendants, but the town had been allowing visitors to the park to drive on the beach, causing environmental damage. In the end, a sum of 7 million dollars was paid to the owners of the property, in exchange for the Town of Carolina Beach having full control over the usage of the land.12

Further Research

African American Research Guide

Researching African American ancestors can be challenging and often requires creative researching methods. This research guide, compiled by our experts, lists places to search and tips to help you on your way.

The 10 Million Names Map

10 Million Names is an initiative from American Ancestors to recover the names and stories of the estimated 10 million men, women, and children of African descent who were enslaved in America between the 1500s and 1865. Created for this project, this interactive map illustrates the rise and fall of slavery, showing how many enslaved and free people of African descent lived in the continental U.S. at each time period.

Notes

1 At first glance, the record looks like it says 1920. However, the certificate was filed in 1923, and the date of burial could read either 1920 or 1923. A closer examination of the date of death looks makes it seem as if it could be either year, but I do not believe they would hold the body for exactly three years between death and burial.

2 Kahrl, Andrew W. The Land Was Ours: How Black Beaches Became White Wealth in the Coastal South . University of North Carolina Press, 2012. 155.

3 "North Carolina, County Marriages, 1762-1979 ," database with images, FamilySearch. Rufus Freeman and Martha Lowe, 25 Oct 1902

4 1910 U.S. Federal Census, Federal Point Township, New Hanover, North Carolina. Rufus Freeman household.

5 "North Carolina Marriages, 1759-1979", database, FamilySearch . Rufus R. Freeman and Theresa Brown, 1921.

6 1920 U.S. Federal Census, Federal Point Township, New Hanover, North Carolina. Rufus Freeman household.

7 1930 U.S. Federal Census, Wilmington, New Hanover, North Carolina. Theresa Freeman household.

8 "North Carolina, Department of Archives and History, Index to Vital Records, 1800-2000," database, FamilySearch, Archie L Freeman, Oct 1930.

9 1870 Federal Census, New Hanover County, North Carolina. Bose Freeman household.

10 Wills, Vol H2, 1897-1904in “North Carolina US Wills and Probate Records 1665-1998,” online database at Ancestry.com. 532.

11 Kahrle, This Land Was Ours. 156.

12Preston Lennon, “Carolina Beach Announces $7M Deal to Settle Freeman Park Lawsuits,” Port City Daily, November 20, 2021, https://portcitydaily.com/local-news/2021/11/20/carolina-beach-announces-7m-deal-to-settle-freeman-park-lawsuits/.

Share this:

About Zobeida Chaffee-Valdes

Zobeida leads the volunteer program for Database Services and assists with creating and improving the database offerings on the American Ancestors website. She works with a large group of dedicated volunteers to accurately index historical records and make them accessible to a wide audience. She started her career with American Ancestors in 2023 as a Researcher, where she specialized in African American genealogy and family archiving projects. Her passion for archival studies and information science led her to join the Database team in 2024. Zobeida graduated from Northeastern University in 2023 with a Masters of Arts in Public History, with a certificate in Digital Humanities. While completing her degree, she worked for Boston African American National Historic Site, Essex National Heritage Area, and Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections. Zobeida graduated from Carleton College in 2019, where she studied History and Archaeology.View all posts by Zobeida Chaffee-Valdes →