This year marks the 250th anniversary of the Boston Tea Party, which occurred on December 16, 1773. 92,000 pounds of tea from the British East India Company was destroyed by members of the Sons of Liberty to protest the Tea Act of May 10, 1773. The tax on tea (as well as glass, lead, paint, and paper) had already existed since the passing of the 1767 Townshend Revenue Act, but this new Act gave the British East India Company a monopoly on tea sales in the American colonies. Many Americans were upset by these policies and the taxes imposed by Britain without their representation in Parliament, resulting in the Revolutionary phrase “no taxation without representation.”

This year marks the 250th anniversary of the Boston Tea Party, which occurred on December 16, 1773. 92,000 pounds of tea from the British East India Company was destroyed by members of the Sons of Liberty to protest the Tea Act of May 10, 1773. The tax on tea (as well as glass, lead, paint, and paper) had already existed since the passing of the 1767 Townshend Revenue Act, but this new Act gave the British East India Company a monopoly on tea sales in the American colonies. Many Americans were upset by these policies and the taxes imposed by Britain without their representation in Parliament, resulting in the Revolutionary phrase “no taxation without representation.”

There is a new lineage society for descendants of participants in the Boston Tea Party, their families, and those involved in the making of colonial rebellion in Boston, created by American Ancestors in partnership with the Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum. Although I knew I had no ancestors living in Boston at the time of the Tea Party, I began searching for ancestors living near Boston at the time who might meet one of the eligibility requirements.

I was able to access an obituary of one of my ancestors using the Early American Newspapers database from Readex, which is available to search for American Ancestors members. From this, I began to learn much more of his involvement and contributions during the beginnings of the American Revolution.

Rev. Benjamin3 Prescott (Jonathan2, John1) was born at Concord, Massachusetts, on September 16, 1687 to Captain Jonathan and Elizabeth (Hoar) Prescott. His father was a doctor who, along with John Horton, had obtained recognizance for Ann Sears during the Salem Witch Trials. His maternal grandfather, John Hoar, had secured the release of Mary Rowlandson from Nipmuc captivity at Redemption Rock. Benjamin was closely associated with many patriots, including his great-nephew, Dr. Samuel5 Prescott (Abel4, Jonathan3, Jonathan2, John1), who was the only man who completed the midnight ride of Paul Revere, and his brother Abel Jr., was also involved. Paul Revere referred to Samuel as a "high son of Liberty," resulting in speculation that Samuel had ties to the Sons of Liberty or acted as a courier for the Committees of Correspondence prior to the start of the Revolution. Benjamin’s granddaughter married Roger Sherman, the only person to sign all four of the great state papers of the United States: the Continental Association, the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the Constitution.

Benjamin’s 1777 obituary in the Boston Gazette gave detailed information on Benjamin’s life and career, though a more extensive biography can be found in Sibley’s Harvard Graduates. Benjamin was educated at Harvard and graduated in 1709, then ordained as pastor of the 3 rd Church in Salem on September 23, 1713, where he served for 45 years. He then became a magistrate in Essex County until the time of his death on May 20, 1777, at age 90.

“He had great political as well as theological knowledge: He well understood the laws, the rights, and the interest of his county, and defended them with great strength of reason, as well as a generous warmth of heart. In this service his pen was frequently and largely employed, more especially since the commencement of the present important contest, tho’ he concel’d his name…”

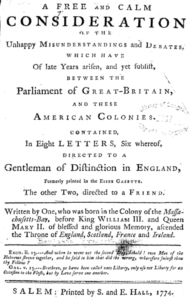

At first, I was disheartened that Benjamin concealed his name, worried that I might not be able to locate the writings he authored leading up to and during the American Revolution. However, I could understand his need to hide his identity. I was pleased to find that his writings from 1767 (the same year as the Townsend Acts) up to 1774 were published together in 1774 under a hefty title: A Free and Calm Consideration of the Unhappy Misunderstandings and Debates, Which Have of Late Years Arisen, and Yet Subsist, Between the Parliament of Great-Britain, and These American Colonies Contained, in Eight Letters, Six Whereof, Directed to a Gentleman of Distinction in England, Formerly Printed in the Essex Gazette. The Other Two, Directed to a Friend. Written by One, Who Was Born in the Colony of the Massachusetts-Bay, Before King William III. and Queen Mary II. of Blessed and Glorious Memory, Ascended the Throne of England, Scotland, France and Ireland.

In Letter VIII. To A Friend, Massachusetts-Bay, June 9, 1774, Benjamin reflected on the events of the Boston Tea Party and those which occurred directly after. In particular, Benjamin disagreed that Parliament, with support of the King, allowed for the blockade of the Boston Harbor in retaliation for the Tea Party, and considered this a worse crime and a greater wrong than the rebellion perpetrated by the Sons of Liberty. Benjamin was aggrieved that East-India Company of Merchants in London had not followed the legal and proper channels to punish the “criminals” who destroyed their property, arguing that due process should have fallen to the local magistrates rather than Parliament.

“And is it not Matter of great Surprize and Wonderment, that when those whose Property the Tea was, had made no Demand for Satisfaction, nor taken any legal Methods for the Recovery of the Damages they sustained by the Destruction of it, that the Parliament should espouse their cause, and at all Adventures, forcibly block up the Harbour of Boston, and render inaccessible and useless, the Wharves and landing Places of eleven other Towns, that border upon it. And that without giving any previous notice thereof, or Opportunity for the Persons concerned in, or affected thereby, to offer what they or any of them, might have to offer in their own Vindication? Verily I think, that if this had been done by any, but this Supreme Legislature, it must have been judged a more unjustifiable Act of Violence, and a vastly greater Wrong, than that done to the East-India Company, by unknown Persons, but such as were represented in the Boston Prints as a Gang of Savage Mohawks.”

It seems that Benjamin considered the actions of the Sons of Liberty a crime, though he was sympathetic to their plight because of the hostile policies which began in 1765, and which he had been writing about since. He was adamant that legal methods should always be used in a republic.

Could you have an ancestor who witnessed the events of the Boston Tea Party? American Ancestors has compiled a wealth of resources to help you get started in your research, from databases to articles, free lectures, and more. Explore Boston Tea Party Resources