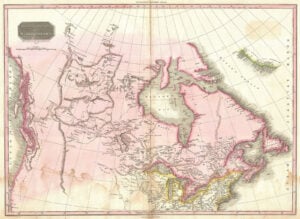

For a country which gained its independence from the United Kingdom just 155 years ago, Canada has gone through a significant number of changes to its internal structure and boundaries. The relatively frequent shifting of jurisdictions among the oft-renamed areas has proven to be troublesome to genealogical researchers.

Before delving into the history of Canadian political geography, it is important to be aware of a few notable terms and concepts. First, is the difference between a Territory and a Province. A Province receives its power and authority from the Constitution Act of 1867, whereas Territories have powers delegated to them by Parliament. 1 Presently, Canada is composed of ten provinces and three territories, a count which changed most recently in 1999 with the creation of the Territory of Nunavut. Additionally, parts of modern-day Canada were once considered distinct Colonies of the United Kingdom, including the colonies of British Columbia (1858-1866), Prince Edward Island (1604-1873), and Newfoundland (1610-1907).

To answer the question posed by the title of this piece, Upper and Lower Canada were not named for their physical positions in relation to one another, but instead to the Great Lakes and the headwaters of the Saint Lawrence River. Upper Canada was above these headwaters, while Lower Canada was farther downriver—hence, their names.2 It should be noted that in 1841, the two colonies of Upper and Lower Canada were merged into the Province of Canada, which was then divided into two parts: Canada East (formerly Lower Canada, presently Quebec) and Canada West (formerly Upper Canada, presently Ontario).3

The first colonial division of the land that would become Canada took place in 1534 with the establishment of New France, although there were no permanent settlements until 1604.4 In 1670, the Hudson Bay Company founded Rupert’s Land, a territory developed in 1670 which lasted for two centuries before the company surrendered the land to the British Crown in 1870.5 Following the end of the Seven Years’ War, Quebec was ceded to Great Britain, who renamed it the Province of Quebec in 1763. This name would survive until 1791, when a constitutional act divided the province at the Ottawa River, establishing the Province of Upper Canada under the English legal system with mostly English speakers, while Lower Canada was populated largely by those with French ancestry.6 As previously mentioned, 1841 was a critical date in Canada’s evolution, as it saw the proclamation of the British North America Act which abolished the legislatures of Upper and Lower Canada and created a new United Province of Canada. Despite the union, two distinct colonies were retained, with Canada East observing French civil law and Canada West utilizing English common law. 7

The single most consequential event in Canadian history occurred on 1 July 1867 with the unification of the three existing Provinces—Canada (which was then divided into Quebec and Ontario ), Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick)—into the Dominion of Canada. 1870 saw the single largest formal addition to the dominion when the United Kingdom relinquished the unorganized land in the North-west Territory and Rupert’s Land into the North-west Territories (later spelled Northwest). 8 A small rectangular area around the newly-acquired city of Winnipeg was established as the Province of Manitoba.9 It was only one year later that a sixth province was founded, when the colony of British Columbia joined the dominion.10

Despite their initial resistance, Canada’s smallest province by land area and population, Prince Edward Island, which was facing a financial crisis, was united with Canada in 1873. 11 In 1876, the District of Keewatin, which consisted of the land north of Manitoba between the western border of Ontario and the North-west Territories was developed.12 This district would officially become one of the four districts of the North-west Territories in 1905, and would continue to exist until it was officially dissolved in 1999 with the creation of the Territory of Nunavut.

To complicate matters further, in 1882, the North-west Territories were divided into provisional districts including Alberta, Assiniboia, Athabasca, and Saskatchewan. They were classified as provisional to distinguish them from the District of Keewatin, which had a more autonomous standing. 13 In an effort to ease administration, four additional districts—Franklin, Ungava, Yukon, and Mackenzie—were created in 1895. 14

A massive growth in population as a direct result of the Klondike Gold Rush saw the Yukon District become the Yukon Territory in 1898.15 While the Gold Rush brought as many as 100,000 prospectors to the area, today, it is Canada’s second least populous province or territory, with a population of just under 44,000. 16 One of the final shifts in the political geography of Canada took place in 1905, when Alberta and Saskatchewan were formed as provinces when they absorbed land from the North-west Territories.17

In 1907, Newfoundland became a British Dominion, a status it would maintain until 1949 when it became Canada’s tenth province as Newfoundland and Labrador.18 Five years later in 1912, the 60th parallel north became the official northern terminus of the provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta, establishing a border which still exists today.19

At the turn of the 21st century, one final significant change was made when the Territory of Nunavut was created from the eastern portion of the Northwest Territories. Since that time, only names have been subject to change, as Newfoundland became Newfoundland and Labrador in 2001 and the Yukon Territory became simply Yukon in 2003.20

Over the course of the last four centuries, the geographic boundaries within Canada have shifted radically, leading genealogical researchers down a confusing path when trying to locate records for their ancestors. While the bounds of Canada’s ten provinces and three territories have long remained unchanged, it is important to remember that prior to the 20th century, shifting borders were an almost annual occurrence, which may affect where records can be found. With this in mind, when all else fails, historic maps can be the most helpful resource in your arsenal.

Notes

1 Government of Canada, “Provinces and Territories,” https://www.canada.ca/en/intergovernmental-affairs/services/provinces-territories.html.

2 Dodek, Adam, The Canadian Constitution, (2016).

3 “The Province of Canada” The Canadian Encyclopedia, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/province-of-canada-1841-67.

4 Riendeau, Roger E., A Brief History of Canada, (2007), pg. 36.

5 Hudson’s Bay Company, “Deed of Surrender,” https://www.hbcheritage.ca/history/fur-trade/deed-of-surrender.

6 Hudson’s Bay Company, “Deed of Surrender,” https://www.hbcheritage.ca/history/fur-trade/deed-of-surrender.

7 “The Province of Canada” The Canadian Encyclopedia, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/province-of-canada-1841-67.

8 Hudson’s Bay Company, “Deed of Surrender,” https://www.hbcheritage.ca/history/fur-trade/deed-of-surrender.

9 Begg, Alexander, The Creation of Manitoba: or, A history of the Red River Troubles , (Toronto, Ontario, 1871), pg. 306.

10 “Order of Her Majesty in Council admitting British Columbia into the Union, dated the 16th day of May, 1871,” Government of Canada, https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/csj-sjc/constitution/lawreg-loireg/p1t41.html#:~:text=Order%20of%20Her%20Majesty%20in,16th%20day%20of%20May%2C%201871.

11 “Dominion Day” The Patriot (Prince Edward Island), 3 July 1873.

12 Nicholson, Norman L., The Boundaries of the Canadian Confederation, (Toronto, Ontario, 1979), pg. 113.

13 Acts of the Parliament of the Dominion of Canada , (Ottawa, Ontario, 1886), pg. xviii.

14 Nicholson, Norman L., The Boundaries of the Canadian Confederation, (Toronto, Ontario, 1979), pg. 118.

15 “Yukon and Confederation” The Canadian Encyclopedia, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/yukon-and-confederation.

16 Quarterly Population Estimate, Q3 2022, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000901.

17 Nicholson, Norman L., The Boundaries of the Canadian Confederation, (Toronto, Ontario, 1979), pg. 129.

18 “Newfoundland Act” https://www.solon.org/Constitutions/Canada/English/nfa.html.

19 Nicholson, Norman L., The Boundaries of the Canadian Confederation, (Toronto, Ontario, 1979), pg. 129.

20 “Yukon Act, SC 2002, c 7” https://www.canlii.org/en/ca/laws/stat/sc-2002-c-7/105007/sc-2002-c-7.html.

Share this:

About Zachary Garceau

Zachary J. Garceau is a former researcher at the New England Historic Genealogical Society. He joined the research staff after receiving a Master's degree in Historical Studies with a concentration in Public History from the University of Maryland-Baltimore County and a B.A. in history from the University of Rhode Island. He was a member of the Research Services team from 2014 to 2018, and now works as a technical writer. Zachary also works as a freelance writer, specializing in Rhode Island history, sports history, and French Canadian genealogy.View all posts by Zachary Garceau →