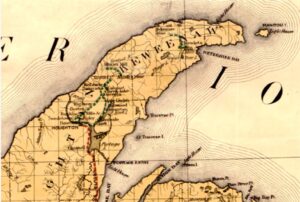

I am incredibly fortunate that I have my dream job, working remotely as a Genealogical Researcher with the Boston-based New England Historical Genealogical Society (NEHGS), while living in my dream location – the remote Keweenaw Peninsula of northern Michigan.

Last week I was sitting in Shute’s 1890 Saloon—an historic watering hole in the city of Calumet, Michigan—reflecting on my good fortune, when I looked up at the television flanking the old Brunswick-stained glass canopy and recognized a familiar ship on the screen. The film was a 1952 movie called Plymouth Adventure, a rather questionable depiction of the Mayflower landing on Plymouth Rock. It got me thinking about how I came to be in this spot: a Finn drawing a paycheck from a Boston organization in remote northern Michigan. Surely, I represent a strange confluence of events.

So what is my connection to northern Michigan? My ancestors traveled across the ocean in search of a better living, lured by the rich copper mines in the region. The industry would draw countless immigrants, including my great-grandfather Kustaa Mannisto, who emigrated from Ylivieska, Finland in 1896, and my great-grandfather Mikko Wanhala, who emigrated from Vaasa, Finland in 1887. My great-grandfathers would both meet their brides and live out the remainder of their days in the Keweenaw Peninsula. Over one hundred and twenty years later, my family still owns the Männistö maatila (farm) near the old site of the Phoenix Mine in Keweenaw County, and my father’s cousin still owns the Wanhala home on a narrow, windy country road just a few miles from where I sit. The road, coincidentally, is called Mayflower Road. Hmm…the Boston connection again.

Ok, so my ancestors came here because they saw opportunity in the huge mining economy—but how did these great mines get here in the first place? That’s when the Boston brick hit me: my favorite northern Michigan town was literally built with Boston money.

Just down the street from Shute’s 1890 Saloon stood the old office of the Calumet & Hecla Mining Company, whose first president was Quincy Adams Shaw—a Boston Brahmin, the son of Robert Gould Shaw and Elizabeth Willard Parkman.1 The building itself was built by Boston architects Shaw and Hunnewell.2 In fact, the town of Calumet, Michigan was known as a “Boston town.” There is a small ghost-town just 10 miles away that was once known as Boston Location.

The Calumet & Hecla Mining Company, now the Keweenaw National Historic Park Headquarters, Calumet, Houghton County, Michigan, photo courtesy of the National Park System

The Calumet & Hecla Mining Company, now the Keweenaw National Historic Park Headquarters, Calumet, Houghton County, Michigan, photo courtesy of the National Park System

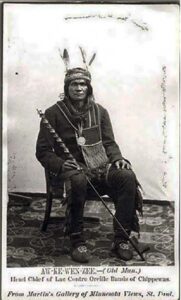

Well, I’m a genealogist, so I keep digging. What brought wealthy Bostonians like Quincy Adams Shaw and his brother-in-law Alexander Agassiz (who is memorialized in a statue two blocks away) to this neck of the woods to start copper mines in the first place? For that answer, we need to go back one hundred and eighty years. On 4 October 1842, the Ojibwe Indian Tribe—also known as the Chippewa—signed a treaty ceding their rights to this land along the shoreline of Lake Superior.3 The treaty, known as the Treaty of La Pointe 1842, was signed by forty-one Ojibwe citizens. It would ultimately be the catalyst for my paternal ancestor’s arrival in America, and the ongoing connection I find myself having with the great city of Boston, Massachusetts.4

Aw-Ke-Wen-Zee (Old Man), 1854, one of forty-two Chippewa leaders who signed the Treaty of La Pointe 1842, photo courtesy of Martin's Gallery, Minnesota Historical Society, Saint Paul, Minnesota.

Aw-Ke-Wen-Zee (Old Man), 1854, one of forty-two Chippewa leaders who signed the Treaty of La Pointe 1842, photo courtesy of Martin's Gallery, Minnesota Historical Society, Saint Paul, Minnesota.

The United States government certainly knew what they were gaining with the signing of the Treaty of La Pointe 1842. In 1841, the well-known Michigan geologist Douglass Houghton published the results of a geological survey he did on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and the land’s rich copper deposits.5 In 1843, the United States Government would open a mineral land office in Copper Harbor, the Keweenaw’s most northern point, and Houghton’s geological findings would spread to east coast investors like Shaw and Agassiz.6 In 1844, the newly formed Boston Copper Harbor Mining Company would start America’s first mining expedition just outside Copper Harbor.7 The Boston Brahmins’ initial investments versus return would not be deemed profitable, but in time, the area which has been affectionally deemed “Copper County” would surpass investors’ hopes and flourish under the Calumet & Hecla Mining Company. 8

At some point in my ruminations, the questionable movie on the TV lost my attention, as the female passengers on the cinematic Mayflower sported low-cut dresses paired with white bonnets—a historical faux pas that woke me as quickly as smelling salts. Walking out of Shute’s into the cobblestone street, I felt an even deeper connection to my ancestors. I bet that I’m not the first Finn to sit on a bar stool in Shute’s Saloon paying for my drink with wages that originated in Boston. I was reminded of the Liam Callanan quote: “We all carry, inside us, people who came before us.”

Notes

1 Kathryn Bishop Eckert, Society of Architectural Historians, Keweenaw History Center (Calumet and Hecla Public Library) and New England Historical Society, Stonington, Maine, A Brief History of the Boston Brahmin, updated 2022.

2 Eckert, Society of Architectural Historians,Keweenaw History Center (Calumet and Hecla Public Library).

3 The Indigenous Digital Archive sponsored by The Museum of Indian Arts and Culture (IDA), Santa Fe, New Mexico, from the U.S. National Archives collection of 374 Ratified Indian Treaties, Treaty Between the United States and the Chippewa Indians of the Mississippi and Lake Superior, Signed at La Pointe of Lake Superior, Wisconsin Territory, with Schedule of Claims, Ratified Treaty 242, created 4 October 1842.

4 The Indigenous Digital Archive, Treaty Between the United States and the Chippewa Indians of the Mississippi and Lake Superior, Signed at La Pointe of Lake Superior, Wisconsin Territory, with Schedule of Claims, 4 October 1842.

5 Theodore J. Bornhorst and Lawrence J. Molloy, Douglass Houghton- Pioneer of Lake Superior Geology, Superior Geology, A.E. Seaman Mineral Museum Web Publication 4, 2017, Michigan’s First State Geologist, page 5.

6 National Park Service, Keweenaw Historical National Park, Michigan Timeline of Michigan Copper Mining Prehistory 1850, timeline year: 1843, Copper Harbor mineral land office opens and Bornhorst and Molloy, Douglass Houghton- Pioneer of Lake Superior Geology, Superior Geology, A.E. Seaman Mineral Museum Web Publication 4, 2017, Michigan’s First State Geologist, page 5.

7 National Park Service, Keweenaw Historical National Park, Michigan Timeline of Michigan Copper Mining Prehistory 1850, timeline year: 1844, Boston Cooper Harbor Mining Company starts mining outside of Copper Harbor.

8 Bornhorst and Molloy, Douglass Houghton- Pioneer of Lake Superior Geology, Superior Geology, A.E. Seaman Mineral Museum Web Publication 4, 2017, Michigan’s First State Geologist, page 5.

Share this:

About Kimberly Mannisto

Kimberly Mannisto earned her B.A. in English with an emphasis in creative writing from Western Michigan University. She joined American Ancestors/NEHGS in Research and Library Services; she also is a certificate holder from the Boston University Genealogical Research Certificate program. She was introduced to genealogy at a young age and has over 30 years of experience in research and report writing. Areas of expertise: Early Pennsylvania settlers, Colonial New Jersey, Quaker records, Midwest (Michigan and Ohio), Finnish, DNA, Descendancy research, Scottish and English hereditary peerage titles, and Scottish genealogy with a particular interest in genetic markers and male clan descendancy.View all posts by Kimberly Mannisto →