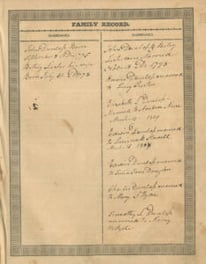

Page from an original family bible, with vital records for the family of John Dunlap (1775-1848) and his wife, Betsey Lester (1778-1850).

Page from an original family bible, with vital records for the family of John Dunlap (1775-1848) and his wife, Betsey Lester (1778-1850).

Discovering the existence of a family bible can be one of the most thrilling revelations in family history research. Original Bibles possess what archivists refer to as artifactual value: intrinsic worth as objects apart from their content. We often revel in family heirlooms because their very survival is a matter of chance. At least one representative from each succeeding generation must cherish the item, or serendipitously leave it forgotten in a secure location for it to be recovered decades later.

For genealogists, family Bibles can also convey unique information. Heirloom Bibles often contain records of birth, marriage, and death dates—usually scrawled on the Bible’s inside flyleaf—and can serve as proof of parentage in the absence of a vital or church record.

Many town clerks in colonial New England began recording births, marriages, and deaths shortly after their town’s establishment, but these vital registers are notoriously incomplete. To account for recordkeeping lapses, online databases of compiled vital records often combine information from various sources, such as church records and tombstone epitaphs, with extant town records. State legislation requiring towns to submit returns of vital events ensured a more complete body of records, but came later in history than one might expect. Massachusetts became the first U.S. state to initiate centralized registration in 1841. In some states, like New York and Pennsylvania, civil registration began later in the nineteenth century (1881 and 1885, respectively), though some larger cities established their own systems of registration earlier. The Southern and Midwestern states enacted vital registration laws latest of all, with the South mandating the registration of births and deaths between 1899 and 1919, and the Midwest between 1880 and 1920.1

Bibles are often the sole source of vital information for a family living in a certain locale within a given time period—but how do you track these valuable artifacts down if you aren’t lucky enough to maintain them in your own home?

Military Pensions

The credibility of early pension applications is built upon family-supplied information, usually relayed through an interview with the pensioner or his widow at the local courthouse, but occasionally from Bible transcriptions. When I first began practicing genealogy, I was delighted to find a page from a family Bible in a digitized Revolutionary War pension application—apparently torn out and given up to the pension bureau! In other cases, the pension applicant’s recollections of his or her birthdate from the family Bible are written in an affidavit.

Historical Societies, Libraries, Universities

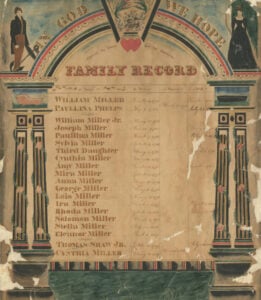

Hand drawn and colored family register listing birth, marriage, and death dates for the William and Paullina Phelps Miller family.

Hand drawn and colored family register listing birth, marriage, and death dates for the William and Paullina Phelps Miller family.

Local, regional, and state archives are troves of unique materials acquired from area residents. With so many repositories digitizing their collections in recent years, you may find the family Bible you’re looking for online. Almost 400 Bible records from the R. Stanton Avery Special Collections can be searched at the Digital Library and Archives from American Ancestors.

The State of Virginia initiated vital registration in 1853, but local clerks did not always submit their birth, marriage, and death returns to the Bureau of Vital Statistics. Additionally, between 1896 and 1912, Virginia did not mandate the reporting of vital statistics at all.2 Recognizing the lacuna created by these inconsistencies, the Library of Virginia’s digital collections include images of 6,800 Bible records, both original and transcribed, which can provide researchers with birth, marriage, and death information. Learn more about the LOV Bible Records.

University archives should also be consulted in your search for family Bibles. Contact repositories in the area where your ancestors lived to determine whether they have Bibles in their collections, in digital or manuscript format. Most Bibles from colleges and universities are cataloged with other manuscript items and discoverable online. Several examples of such collections include:

- Bible Collection, [1772?]-1911 (Briscoe Center for American History at University of Texas at Austin)

- William Bennett Bizzell Bible Collection (University of Oklahoma)

- Family Bible Collection (Edward H. Nabb Center for Delmarva History and Culture at Salisbury University, Maryland)

- Index to Bible and Family Records Collection from the Genealogical Society of New Jersey (Special Collections and University Archives at Rutgers University)

- Family Bible Collection (Special Collections at Cedarville University, Ohio)

DAR

The National Society Daughters of the American Revolution maintains digital copies of their nineteenth-century Genealogical Research Committee Reports, many of which enclose Bible transcriptions submitted to the Society. While digital images of the GRC Reports are only available onsite at the DAR Library, the public can search an index of 84,000 bible records from GRC Reports on the DAR’s website. If a relevant entry is located, up to 10 copies of specific pages may be ordered from the DAR Library for a $15 fee. Search the DAR’s online database of Bible Records and Transcriptions.

Late and incomplete vital registration is a universal frustration among genealogists. When confronting a lack of official records, consider that a substitute might exist—one written in your ancestor’s own hand!

Notes

1 Family Search. U.S. Vital Records Overview: https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/U.S._Vital_Records_Overview

2 Library of Virginia. “Family Bible Records,” https://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/guides/bible.htm

Share this:

About Jennifer Shakshober

Jen earned a dual B.A. in English and Economics from Westfield State University, an M.F.A. in Creative Nonfiction from Bennington College, an M.L.I.S. in Archives Management from Simmons University, and a certificate in Genealogical Research from Boston University. In 2018, she completed a graduate internship at Old Sturbridge Village's Research Library, where she arranged an early nineteenth century manuscript collection. Areas of Expertise: Massachusetts, Connecticut, Vermont, North Carolina, Virginia, and Maryland.View all posts by Jennifer Shakshober →