To keep the momentum going on middle names amongst presidential families, I’ll discuss one of the more confusing cases, regarding President Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885). The contemporary reporting on his actual name varied considerably and gets repeated even amongst organizations that should have had a more direct relationship with Grant or his descendants.

To keep the momentum going on middle names amongst presidential families, I’ll discuss one of the more confusing cases, regarding President Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885). The contemporary reporting on his actual name varied considerably and gets repeated even amongst organizations that should have had a more direct relationship with Grant or his descendants.

The most authentic source on the matter was the president’s father, Jesse Root Grant (1794-1873), who wrote a serial column in the New York Ledger on “Early Life of Gen. Grant.” On 14 March 1867 he wrote “I believe he went by the name ‘Uncle Sam,' at [West Point] on account of his initials … he was christened Hiram Ulysses; but he was always called by the latter name, which he himself preferred when he got old enough to know about it. But Mr. Hamer, who nominated him as a cadet, knowing Mrs. Grant’s name was Simpson, somehow got the matter a little mixed in making the nomination, and sent the name in Ulysses S. Grant instead of Hiram Ulysses Grant. My son tried in vain afterwards to get it set right by the authorities, and I suppose he is now content with his name as it stands.”

“It was at this time and by a blunder of Gen. Hamer, that his original name, Hiram Ulysses, was exchanged for that which he has since made so famous."

An 1868 biography on then-presidential candidate Ulysses S. Grant and his running mate Schuyler Colfax provides a somewhat similar account: “It was at this time and by a blunder of Gen. Hamer, that his original name, Hiram Ulysses, was exchanged for that which he has since made so famous. General Hamer, in nominating him, had reported his name to the Examiner at West Point as Ulysses S. Grant, probably with some indistinct idea that he had two names, and that, as he was always called Ulysses, the second name was probably Simpson, from his mother’s maiden name. However this may be, the young cadet found himself on his admission entered as Ulysses Sidney Grant. He endeavored, but in vain, to have it changed on the records of the Academy, and when he graduated, he substituted Simpson for the Sidney which he had always repudiated, and thenceforth wrote the name U.S. Grant.”

Without access to West Point’s records, and taking in his father’s account and the 1868 summary, the future president never considered Simpson his middle name. That did not prevent numerous newspapers from calling the president Ulysses Sidney Grant or Ulysses Simpson Grant. I could summarize the several contemporary records that do not show a middle name, but most records of this time only listed someone by their middle initial. However, the situation takes an interesting turn in how the briefly-mistaken middle name that turned into Grant’s middle initial was used by his namesake descendants.

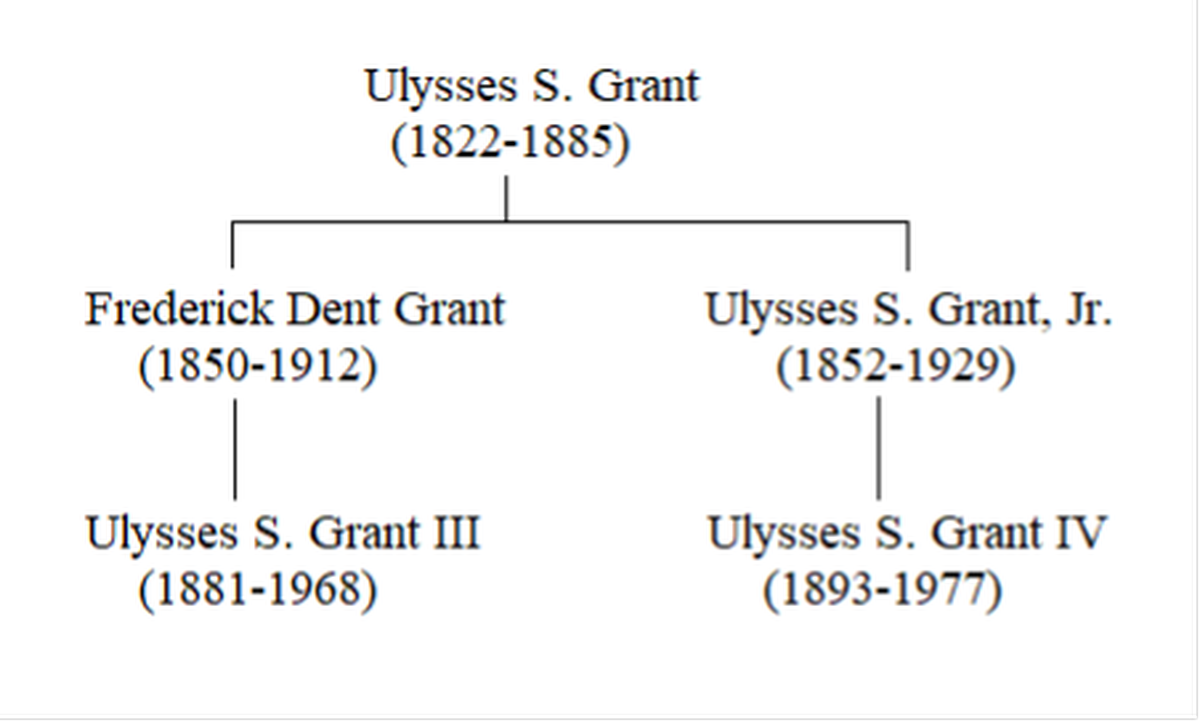

President Grant had a son named Ulysses as well as two grandsons of the same name, all identified by suffixes in a modern sense:

President Grant’s sons and grandsons were involved in a few hereditary societies relating to General Grant’s service in the Civil War as well as their revolutionary and colonial ancestors. Maj. Gen. Frederick Dent Grant was the first governor general of The Order of the Founders and Patriots of America 1896-98 and again 1910-12, a position his son Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant III held 1933-35, and Ulysses S. Grant IV was an associate of this order. Publications of this society vary in whether “Simpson” or “S.” is the middle name, although most of the earlier directories leave it as simply “S.” Frederick Dent Grant and Ulysses S. Grant III were both members of the Mayflower Society through their descent from Mayflower passenger Richard Warren. Frederick’s application in 1903 and Ulysses’ in 1950 both give the president the middle name of Simpson (the latter citing the Delano genealogy), and although the application of the younger Ulysses is typed “Ulysses Simpson Grant III,” it is signed “Ulysses S. Grant 3rd.”

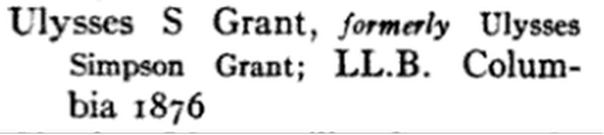

However, I think the most telling indication of the family’s preference is the annual reports from Harvard College for Ulysses S. Grant, Jr., who graduated in 1874. I reviewed the class reports for the Class of 1874 up through 1914, and the president’s son is always listed as “Ulysses Simpson Grant, Jr.” Then, beginning in the 1915 Quinquennial Catalogue of the Officers and Graduates of Harvard University is the following entry for the class of 1874:

The same goes for his subsequent class reports. What happened in 1915? Ulysses’ son, Ulysses S Grant IV also graduated from Harvard, and his class reports and alumni directories never repeat the misattributed middle name, and interestingly these Harvard reports also omit the period after S, while most other records still included the period.[1]

This is a misattribution that will never go away, nor should it. As much as General Grant tried to correct this error himself, this is one case that really stuck and was repeated infinitely in reports on the president, his son, and grandsons. As I noted in a previous post on presidential namesakes, there were 35 men named Ulysses S. Grant enumerated in the 1900 census, and certainly the majority of those men really did have the middle name Simpson!

Note

[1] The use of the period after the S in the single letter middle name of Harry S. Truman was also discussed in the comments of my previous post on Presidents in the 1950 census. While President Truman frequently signed his name with a period after the S., Truman, likely in jest, apparently initiated the “period controversy” in a 1962 interview with a journalist. While the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum maintains the period after the S., the Harry S Truman Birthplace State Historic Site does not. The Harry S. Truman Little White House in Key West largely maintains the period, except for one graphic on the main homepage.

Share this:

About Christopher C. Child

Chris Child has worked for various departments at American Ancestors since 1997 and became a full-time employee in July 2003. He has been a member of American Ancestors since the age of eleven. He has written several articles in American Ancestors, The New England Historical and Genealogical Register, and The Mayflower Descendant. He is the co-editor of The Ancestry of Catherine Middleton (American Ancestors, 2011), co-author of The Descendants of Judge John Lowell of Newburyport, Massachusetts (Newbury Street Press, 2011) and Ancestors and Descendants of George Rufus and Alice Nelson Pratt (Newbury Street Press, 2013), and author of The Nelson Family of Rowley, Massachusetts (Newbury Street Press, 2014). Chris holds a B.A. in history from Drew University in Madison, New Jersey. Areas of expertise: Southern New England, especially Connecticut; New York; ancestry of notable figures, especially presidents; genetics and genealogy; African-American and Native-American genealogy, 19th and 20th Century research, westward migrations out of New England, and applying to hereditary societies. Chris has lectured on these topics and edits the genetics and genealogy column for American Ancestors.View all posts by Christopher C. Child →