Recently I was researching marriage records in Vermont and was reminded of the existence of Gretna Green towns in Colonial New England in the mid-eighteenthcentury. It turned out some English customs were just too convenient to leave behind, and British colonial towns like Chester, Vermont continued to mirror the infamous Gretna Green found just over the southern border of Scotland. We have likely encountered more references to the notorious town and hasty marriages in historical romance novels than we have in our own genealogical research. Still, it made me wonder about the origins of the scandalous towns and the non-traditional marriage custom the new inhabitants continued to practice after arriving in the New England colonies.

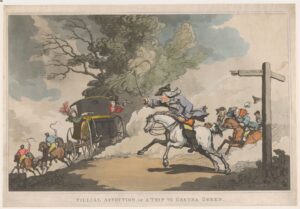

Gretna Green, the first town a runaway couple would enter when they fled over the Scottish border, gained attraction after England and Wales enacted the “Clandestine Marriage Act of 1753.” The law was also known as “Lord Hardwick’s Marriage Act” after the lawyer and Chancellor of Great Britain who brought the proposal to the floor of Parliament.[1]

Until that point in England and Wales’s history, marriage was primarily validated by verbal consent between two parties, and even girls as young as twelve could marry against their parents’ wishes.[2] It was the court case of Campbell vs. Cochran that prompted Lord Hardwick to propose the law. In this case, one Captain Campbell failed to disclose to Jean Campbell, the mother of his three children, publicly acknowledged as his wife for twenty years, that he had secretly married a woman named Magdalena Cochran prior to his relationship with her.[3] Imagine Mrs. Campbell’s surprise when, after the death of her husband, another woman filed for pension rights as the widow of Captain Campbell.[4]

It was the court case of Campbell vs. Cochran that prompted Lord Hardwick to propose the law.

A long court battle ensued and the intent of Harwick’s law was to stop these unsanctioned marriages and provide formal and legal documentation of a marriage’s existence, a necessity when determining legal rights like property claims and a widow’s pension.

Prior to the “Clandestine Marriage Act of 1753,” as in England and Wales, most marriages in early Colonial New England were also primarily civil affairs and only needed verbal acknowledgement that a couple considered themselves husband and wife. Such commitments still lacked marriage certificates, church services, or any formal documentation proclaiming the marriage even took place.

Perhaps one story from a village in Connecticut describes the lack of fanfare best. It has been said that one day a magistrate walked down the street and encountered a couple in town who lived out of wedlock and caused quite a scandal in the community. The magistrate decided to take matters into his own hands:[5]

“John Rogers,” he said, “do you persist in calling this woman, a servant younger than yourself, your wife?”

“Yes, I do.”

“And do you, Mary, wish such an old man as this to be your husband?’

“Indeed, I do.”

“Then by the laws of God and this commonwealth, I, as a magistrate, pronounce you man and wife.”

Whether this story is true or not, the “Clandestine Marriage Act of 1753” also applied to the New England colonies, and it was not long before officials discovered that marriage certificates supplied a new source of income for struggling towns. “Star-crossed lovers” were still not a thing of the past, and Gretna Green towns such as Chester became a popular destination for runaway couples determined to marry. These marriages were often called “Flagg marriages” after Parson Flagg, who performed the clandestine marriages if you could pay the excessive price for the certificate and ceremony.[6] The marriage itself was considered unrespectable in the eyes of society and the romanticism of Gretna Green did not appear to follow the non-traditional marriage custom to Vermont.

Notes

Marriages performed by the Rev. Ebenezer Flagg appear undocumented, but at least half the marriages that took place in Gretna Green between 1794 and 1895 have been documented in the Lang Collection of Gretna Green Marriage Registers and suggestions for further resources regarding Gretna Green and border marriages can be found on Cyndislist.com (https://cyndislist.com/uk/sct/bmd/gretna-green/).

[1] UK Parliament, “The law of marriage,” database online, parliament.uk (https:”//www.parliamnet.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/private lives/relationships/overview/lawofmarriage-/), para 3.

[2] British Heritage, “Where lovers run to wed- a history of Greta Green,” 7 January 2022, database online, Britishheritage (https://britishheritage.com/history/lovers-wed-history-greta-green), para 4.

[3] James Hardy, “History of Hardwick’s Marriage Act of 1753,” 14 September 2016, database online, Historycooperative (https://historycooperative.org/the-history-of-hardwickes-marriage-act/), para 9.

[4] Ibid., para 10.

[5] David Freeman Hawke, Everyday Life In Early America (New York: Harper & Row, 1989), 93.

[6] Jane Merrill and Chris Filstrup, The Wedding Night: A Popular History (Santa Barbara, Calif.: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2011), 121.

Share this:

About Kimberly Mannisto

Kimberly Mannisto earned her B.A. in English with an emphasis in creative writing from Western Michigan University. She joined American Ancestors/NEHGS in Research and Library Services; she also is a certificate holder from the Boston University Genealogical Research Certificate program. She was introduced to genealogy at a young age and has over 30 years of experience in research and report writing. Areas of expertise: Early Pennsylvania settlers, Colonial New Jersey, Quaker records, Midwest (Michigan and Ohio), Finnish, DNA, Descendancy research, Scottish and English hereditary peerage titles, and Scottish genealogy with a particular interest in genetic markers and male clan descendancy.View all posts by Kimberly Mannisto →