If you live in the Greater Metropolitan area of Boston, your water travels a long way to get to your tap. And your palate thanks you! Boston water has a reputation for being straight from the spigot drinkable. Its origin is located 70 miles west of the city in a fresh water source known as the Quabbin.

The controversial Quabbin Reservoir project was roughly a 40-year effort, spanning from the 1890s to the near mid-century. The construction phase occupied the darkest years of the Great Depression.

Two water systems, the Mystic and the Cochituate, were insufficient in size and quality to meet the demands of Boston’s growing population. In 1893, waste problems and foul-tasting water required the State Board of Health to find a region suitable as a solution to the water-purity issues. A commission of engineers, politicians, and surveyors was created to oversee the effort. The purpose of the Metropolitan Water District Commission was to bring quality water to Metro-Boston. This meant, however, that private land and jobs—and memories—would become casualties of eminent domain. And the people most affected would benefit the least. The project was that era’s Big Dig.

“Towns Facing Devastating Flood

Because Boston Must Have Water”

—Boston Globe headline,

November 7, 1920

The work began with the construction of the Wachusett Reservoir, an intersection of the Stillwater, Nashua, and Quinapoxet Rivers. Six and a half square miles in parts of West Boylston, Boylston, Clinton, and Sterling, Massachusetts were flooded for the Wachusett, displacing over 1700 residents. However, once the reservoir was filled in 1908, the Commission realized that the ever-increasing population of Boston would require a bigger water source. They developed plans and pitched them to the State beginning in 1921.

After several delays and reevaluations, the State Legislature voted in 1927 to condemn the Swift River Valley in the western part of Massachusetts. The passing of this legislation ordered the disincorporation of the towns of Enfield, Prescott, Greenwich, and Dana. As the area designated for the new Quabbin Reservoir, the four towns were to be completely flooded. At midnight on April 28, 1938, each town was lawfully dissolved.

The Towns

Enfield was “the richest” town in the Quabbin, it’s population the highest. The Enfield fire department sponsored a “farewell ball” at the town hall on Wednesday, April 27, 1938, the eve of the four towns’ scheduled, legal demise. There were bands, dancing, and theater, with sorrows drowned in free beer.

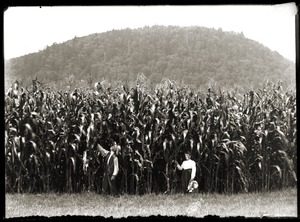

The town of Prescott was mostly farmland and had a population of about 18 at the time of disincorporation, down from its peak of over 750 in 1830.[1] Prescott was so named for Colonel William Prescott (1726–1795) who commanded the Battle at Bunker Hill.[2]

Greenwich, pronounced phonetically, was home to the Dugmar Golf Course, a property constructed on a 163-acre farm that had been purchased for $6850.00.[3] The clubhouse was built of stone and completed in 1926 after the buzz of the coming legislation to condemn the valley. The developers of the course continued to build while they danced with the courts in a near decade-long legal dispute over the value of the land. The original asking price of half a million dollars became $179,000[4] (the equivalent of $1,100 per acre), while displaced residents were reimbursed a paltry $108 per acre for their land.

The buildings of the fourth town, Dana, gathered around a pretty common and housed mills, taverns, and hotels; the town even boasted a singing milkman!

The Work

The valley was referred to as “the most beautiful area in the State.”[5] The Boston Globe reported the four towns contained at least six churches, 13 schools, and 60 summer camps. Sixty! Approximately 2,500 residents were to be displaced this time, some of them descendants of farmers who comprised part of Daniel Shays’s army during the rebellion of the late 18th century. The 14 or so mills that manufactured textiles, hats, and wood products were razed. The active railway system that brought commerce to and from the area was dismantled. Most of the structures in all four towns were burned to the ground; it is said that the valley was on fire for months.[6]

The Quabbin Reservoir would swallow 39 square miles of Massachusetts, an estimated 40,000 acres,[7] far more land than the Wachusett Reservoir had consumed. Two major components of the project began in 1933: the Goodnough Dike and the Quabbin Memorial Park. The dike was named for Xanthus Henry Goodnough, the chief engineer representing the Metropolitan Water District Commission. Goodnough was an 1882 Harvard graduate and, although he worked under the supervision of the Wachusett project engineer, Goodnough had very little engineering experience himself. The dike (actually a dam because it has water on both sides) was over 2,000 feet long and consisted of concrete watertight chambers buried under millions of pounds of earth.

Quabbin Memorial Park, located in the nearby town of Ware, is a cemetery specifically for the 7,600 deceased who were exhumed from the four towns’ cemeteries and transported individually by hearse.[8] Most of the tombstones were moved to the new park, but a few were found underwater during a dive in the late 90s, when a mausoleum was also found in the area of Enfield.

The workers, whom locals called “woodpeckers,” were paid 62.5 cents per hour. The project provided somewhere between 3,000 and 5,000 much-needed jobs during the Depression. Of course, like the Big Dig, politics and patronage played a role. There were many lawsuits, ranging in subject from workers assaulting locals to Governor James Michael Curley misappropriating dollars and contracts to benefit his unemployed Boston constituents. It does not appear that any priority was given to hiring the displaced residents of the Quabbin, who were newly unemployed themselves.

In an often-seen twist in projects of this scale, all records pertaining to the Quabbin work were lost in a fire in March 1939. They were stored in two buildings for the Metropolitan Water District Commission and included files, water samples, motors, and the personal property of the engineers. Nothing was insured.[9] The Quabbin’s forecasted cost was over 60 million dollars.

In June of 1946, a year ahead of schedule, the Quabbin Reservoir was filled. It remains one of the largest unfiltered water sources in the United States[10], with a capacity over 400 billion gallons.

What Remains

The Swift River Valley Historical Society in New Salem houses a collection of “artifacts, stories, and records of the lost towns of the Quabbin Valley.” (Swift River Valley Historical Society, 40 Elm St., New Salem, Mass. https://swiftrivermuseum.org/visit/)

Prescott’s Congregational church was saved and transferred piece by piece to South Hadley, Massachusetts. It is now the Joseph Allen Skinner Museum, under the care of Mount Holyoke College.[11] (Joseph Allen Skinner Museum, 33 Woodbridge Street, South Hadley, Mass. https://artmuseum.mtholyoke.edu/collection/joseph-allen-skinner-museum)

The Dana Town Common remains above water level and can be accessed two miles in from Gate 40 on Route 32A in the town of Petersham. In 2013 the common was listed in the National Register of Historic Places and designated the “Dana Common Historic and Archaeological District.” The foundations of many of the old town’s houses can be found there. (Dana Town Common https://quabbinvalley.wordpress.com/2014/11/05/gate-40-dana-town-common-map/)

The only building remaining in the Quabbin reservation is the clubhouse of the Dugmar Golf Course on Curtis Hill Island. It is surrounded by water.

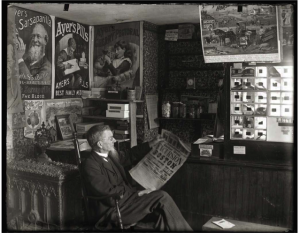

Photo Credits: First three images from Burt V. Brooks Photograph Collection, UMASS Special Collections. Fourth image of Dana is a Metropolitan District Commission real estate photograph, courtesy of the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation, Quabbin Visitor Center, Belchertown, Mass.

Notes

[1] Author unknown, Quabbin Chronology: a timeline of events both large and small that shaped the Quabbin region, https://www.foquabbin.org/chronology.html.

[2] “William Prescott,” Wikipedia Contributors, Wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=William_Prescott&oldid=907039499, last updated 20 Jul 2019 : accessed 21 August 2019.

[3] “Under Quabbin,” PBS.org, WGBY Documentaries, first aired 21 Aug 2001, https://www.pbs.org/video/wgby-documentaries-under-quabbin/ : 1 Aug 2019.

[4] “Under Quabbin,” PBS.org, WGBY Documentaries, first aired 21 Aug 2001, https://www.pbs.org/video/wgby-documentaries-under-quabbin/ : 1 Aug 2019.

[5] “To Make Valley Into Lake,” The Boston Globe (Boston, Massachusetts), 8 February 1927, pg. 11, at Newspapers.com https://www.newspapers.com/image/431098730/ : 20 August 2019.

[6] “Under Quabbin,” PBS.org, WGBY Documentaries, first aired 21 Aug 2001, https://www.pbs.org/video/wgby-documentaries-under-quabbin/ : 1 Aug 2019.

[7] Quabbin Chronology.

[8] Find A Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com : accessed 21 August 2019), memorial page for Harrison L. Thresher (unknown–20 Oct 2003), Find A Grave Memorial no. 97156256, citing Quabbin Park Cemetery, Ware, Hampshire County, Massachusetts, USA ; Maintained by Mark Wing (contributor 47348447).

[9] “Records of the Quabbin Work Lost in Flames,” The Boston Globe (Boston, Massachusetts), 24 Mar 1939, at Newspapers.com : 21 Aug 2019.

[10] “Quabbin,” Wikipedia contributors, Wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Quabbin&oldid=755943306, last updated 21 December 2016 : accessed 21 August 2019.

Share this:

About Susan Donnelly

Susan is a native New Englander and second generation American from a large extended family of artists. She spent two years with the Research Services team, working on several large projects, before joining Newbury Street Press. Prior to NEHGS, Susan was the director and auction coordinator with a premier antique gallery in Boston for two decades and an archival volunteer with the Hingham Historical Society. She received her B.A. in English Literature from Simmons College and holds a Professional Certificate in Genealogy from Boston University. Her research interests include Colonial America, royal ancestry, westward expansion, and U.S. migration trails. Susan is a photographer and potter and collects mid-century modern art.View all posts by Susan Donnelly →