For many of us, Labor Day is synonymous with the last celebration of summer—a time for cookouts, sporting events, and a final day off before the school year begins and autumn arrives. The very existence of the federal holiday (established in 1894) reflects the successes of America’s labor movement at the end of the nineteenth century. Labor federations such as the National Labor Union and the Knights of Labor, were founded in the 1860s to champion the common interests of America’s workforce: better wages, a regulated work week, safe working conditions, and restrictions on child labor. These organizations, however, did not always present a united front—something that was evident in Boston at the turn of the twentieth century and a truth that became personal when researching my great-great grandfather Anders Gustavus Norander.

Anders Gustavus Norander

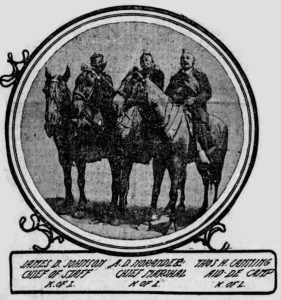

Anders Gustavus Norander, son of Anders and Annie (_____) Norander, was born on 23 December 1866 in Ostersund, Sweden. He arrived in Boston aboard the SS Aleppo on 28 May 1884. After a brief stint living and working in Minnesota, he returned to Boston by 1889, marrying Margaret Teresa Collins on 9 February 1892. He was an active unionist and became recording secretary of the Longshoremen’s Union, Local 7174, Knights of Labor (K. of L.). My family still has his sash—“a broad band of white”[1]—and the union ribbons he wore in 1902 as the Chief Marshal of Boston’s Knights of Labor parade; one of two Labor Day parades held that year.

A longstanding feud

Due to a longstanding feud between the Knights of Labor and the Central Labor Union, Boston actually held two separate Labor Day parades for several years around the turn of the century. The 24 August 1902 issue of the Boston Sunday Post notes, “The reason of this split in the harmony of the Labor Day movement has been the cause of much discussion and perplexity to those not on the inside in labor matters.” Although Chief Marshal of the K. of L. parade, it seems my ancestor was also perplexed and troubled by the split. Within the already referenced article is published a letter Norander wrote to President John R. Crozier of the Central Labor Union:

Dear Sir—Having been elected marshal of [District Assembly 30 (D. A. 30)], K. of L., for the Labor Day parade 1902, I wish to know why the wage-earners of Boston cannot unite in one great labor demonstration, instead of, as for some years past, trying to divide honors in having two distinct parades.The events of this year, in labor matters within Boston, show that, whatever may be said to the contrary, nothing can separate the rank and file from one another, no matter what central organization his local union may be attached to. Therefore, why should men elected to office try to separate the workingmen on Labor’s own holiday?

If you remember when the first so-called split occurred it was by old usage the turn of D. A. 30 to have the right line as well as having the selection of chief marshal, and while there are some who might think that the K. of L. must insist that such must be the case in the next parade of Boston’s labor forces, I wish to state as marshal of D. A. 30, K. of L., that I will be perfectly willing to any agreement as to the selection of right of line and chief marshal, no matter where I am placed in line. Fraternally yours,

A. G. Norander

Marshal of the Division of the K. of L. Parade

According to the article, neither Norander nor the Knights of Labor received acknowledgment from Crozier and the Central Labor Union. The two parades occurred that year, as in previous and subsequent years. Norander led the K. of L. parade, escorted by 700 men from Local 7174, Longshoremen’s Union, and 2,300 men representing freight handlers, sewer workers, stone pavers, trackmen, city employees, freight clerks, railroad workers, and ship carpenters. At the conclusion of the parade, Norander entertained his officers with a banquet at Brigham’s Hotel. As toasts and speeches continued, the main refrain was “it would be better to have only one parade in Boston on Labor Day and that all labor organizations should join in one grand demonstration.”[2]

Eventually, the Knights of Labor folded and the Central Labor Union was divided into local trade unions, now members of the AFL-CIO. As we say goodbye to summer this Labor Day weekend, I will remember my ancestor’s role in Boston’s history and his commitment to a united labor movement.

Notes

[1] The Boston Post, 2 September 1902, p. 1.

[2] The Boston Post, 2 September 1902, p. 8.

Share this:

About Ginevra Morse

Ginevra Morse joined the American Ancestors staff in 2010 as Publications Coordinator, transitioning to the Education team as Online Education Coordinator in 2013. In that role, Ginevra developed the American Ancestors Online Learning Center: an online portal to resources including webinars, online courses, subject guides, and more. In 2014 Ginevra became the Director of Education and Online Programs. Today as Chief Learning & Interpretation Officer she oversees all education programs, including research tours and programs, seminars, workshops, online programs, conferences, group visits, offsite lectures, youth education, and community events. Ginevra previously worked in marketing for an academic, foreign language publisher, where she created webinars and other online learning initiatives for teachers. Ginevra holds a B.A. in anthropology from McGill University in Montréal.View all posts by Ginevra Morse →