The decennial United States Federal Census often forms the backbone of historical research into an unfamiliar family member. By its nature, the census will never be fully comprehensive or exact, but it can serve as a bit of a guard rail, keeping us from going off on an unlikely tangent in our research. Sometimes, though, those 10-year gaps between enumerations can conceal a whole lifetime of information – or in the case of my father’s family, many lifetimes.

The decennial United States Federal Census often forms the backbone of historical research into an unfamiliar family member. By its nature, the census will never be fully comprehensive or exact, but it can serve as a bit of a guard rail, keeping us from going off on an unlikely tangent in our research. Sometimes, though, those 10-year gaps between enumerations can conceal a whole lifetime of information – or in the case of my father’s family, many lifetimes.

My father’s family, the Donegans, hailed from Cork and Limerick, Ireland. The earliest records we have of their family come from passenger lists, where Francis (“Frank”) Donegan and his sister arrived in New York. The two siblings settled in Cortland County, New York in the mid-1800s, and Frank married Ellen McAuliffe, my paternal great-great-great-grandmother (a descendant of early colonial settlers of Massachusetts Bay and Nova Scotia). They resided with Ellen’s parents for a while in Truxton, New York, before moving onto their own farm property. While researching these ancestors, questions started to arise as to the exact number of children that Frank and Ellen may have had. Between interrogations of my own family members, and the independent research conducted by distant relatives, nobody seemed to agree on the total number, and identities, of the descendants of this Donegan couple. I was determined to figure it out for myself!

It seemed like this shouldn’t be such a difficult task: Wouldn’t the census at least give us some idea?

It seemed like this shouldn’t be such a difficult task: Wouldn’t the census at least give us some idea? I easily located the earliest census record, for Truxton in 1870, on which Frank and Ellen appear. As expected, a Francis and “Helen” Donegan resided with Michel and Johanna McAuliffe (Ellen’s parents). They also had a one-year old daughter, Margaret Donegan, in their household.

The next record from 1880 indicates that the family moved to Homer, a nearby town in the same county. Frank and Ellen Donegan resided there with two sons: Frank [Jr.], aged 2, and James, 8 months old. There is no mention of Margaret. So, three kids, maybe one of whom was deceased or resided elsewhere by 1880. Not a huge discrepancy, relatively speaking. I knew of the existance of Frank, Jr. and James (my great-great-grandfather), and their dates of birth and residence in Homer all appeared to make sense based on the rest of what I knew of their life stories.

The next federal census record available for the Donegans came from Cortland, New York in 1900. Besides Frank and James, who both appeared the 1880 record, the family expanded with the birth of four daughters: Nellie, Elizabeth, Anna, and Lena, who all resided at home with their parents. This was, again, in line with my understanding of the family roster, and more or less made sense with the obituary I’d found for Ellen from 1930, which stated that she was survived by three daughters and a son, and was predeceased by one son—this would be Frank, Jr., the chief of the local fire department, who died at the young age of 36 in 1915. Strangely, no mention is made of the more recent loss of her daughter, Elizabeth Marian (Donegan) Adams, in 1924 (or the mysterious Margaret from the 1870 census).

This was, again, in line with my understanding of the family roster...

However, something caught my eye on the 1900 Cortland census that didn’t seem to jibe with the story that was laid out over the course of the intervening decades since 1870.

For a brief period of time, the U.S. Federal Census included the questions, “Mother of How Many Children” and “Number of These Children Living.” A morbid question, surely, but also an incredibly important statistic to track, as well as a rich source of information for genealogical research. According to the 1900 census, Ellen (or Helen) resided with her husband Frank and six children. She had, at this time, given birth to thirteen children, of whom only six were living (ostensibly the same ones residing with her in 1900).

So what became of these children?

The answer to this question is indirectly related to the semi-illegible abbreviation following Frank’s 1880 occupation: Fence Maker LYRR. A Google search won’t tell you what that stands for, but perhaps James’s occupation gives a clue: Brakeman. A second clue can be deduced from a glance at a map of Cortland County, New York, which will show that Truxton, Cortland, and Homer, the towns in which the Donegans resided between 1870 and 1900, are all bordered by the hamlet of Little York, through which the Syracuse & Binghamton Railroad runs.

Little York did in fact have its own passenger railroad station depot, and Frank was not only employed there; he and his young family lived in the station house. Such an arrangement was necessitated by the unusual circumstances under which the station was built: the Syracuse & Binghamton Railroad company initially refused to make Little York a stop on their network, but was finally convinced to do so when the town erected the station of their own accord to secure stoppage of the trains.[1] Without funding from the railroad to maintain the station, the townspeople determined that Frank Donegan, Sr. would be given use of part of the depot building for his residence, in exchange for his upkeep and maintenance of the grounds.

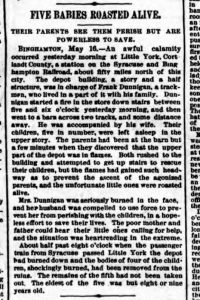

It was in this station depot-turned-homestead where five of Frank and Ellen’s children lost their lives in a tragic accidental fire on 15 May 1877.

It was in this station depot-turned-homestead where five of Frank and Ellen’s children lost their lives in a tragic accidental fire on 15 May 1877.

In another strange omission, while the headstone for these little children was headed with the label “Five children of Frank & Ellen Donegan,” only four of the childrens’ names appeared on the engraved headstone. There were however 5 sets of initials on the foot stone, this last one (M.D.) most likely belonging to the infant babe whose name or gender was never identified in any reports.

From the available records, I have still only managed to find eleven of Frank and Ellen’s thirteen children. I’ve deduced from the years of birth and age ranges that Ellen most likely gave birth to two more children around 1880/81 and 1885/86, after the fire, but I have no proof of this other than the gaps between births, and the enumerator’s assertion that Ellen gave birth to thirteen children. I may one day stroll the Cortland County graveyards of my ancestors to see if another headstone or two exists for Donegan children born in the 1880s. But over the course of my research, I’ve also come to grips with the fact that I may never know who these children were. And that, perhaps, if they had survived, the children who Ellen and Frank conceived later (from whom my family is descended) would never have been born.

The decennial federal census is but one snapshot on one day in the life of each family. The rich stories of our lives are impossible to sum up in a roll-call list. Had I tried to force my research to fit a narrative told by the 1870 and 1880 census records, six or seven of Frank and Ellen’s children might have been overlooked. The census “guard rail” helps us stay on track, but we must also remember to fully explore the context in which each family is found in the census, lest we allow our ancestors and their relatives to slip between the rails, and be lost to history forever.

The decennial federal census is but one snapshot on one day in the life of each family. The rich stories of our lives are impossible to sum up in a roll-call list. Had I tried to force my research to fit a narrative told by the 1870 and 1880 census records, six or seven of Frank and Ellen’s children might have been overlooked. The census “guard rail” helps us stay on track, but we must also remember to fully explore the context in which each family is found in the census, lest we allow our ancestors and their relatives to slip between the rails, and be lost to history forever.

Note

[1] H. P. Smith, ed., History of Cortland County, with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Some of its Prominent Men and Pioneers (Syracuse, N.Y.: D. Mason & Co., Publishers, 1885), 232.

Share this:

About Jennica Bayne

Jennica Bayne joined the Research Services team in 2019. In addition to Colonial New England and Eastern Canadian settlers, her personal research interests include early Quaker settlers of Virginia and North Carolina, their connections to the Underground Railroad, and their interactions with the Cherokee Nation, specifically the Eastern Band Cherokee. Jennica has a passion for data analysis and inheritance patterns, and she is proficient with a wide variety of genetic assessment tools and visual mapping techniques.View all posts by Jennica Bayne →