‘What’s in a name?’ asked Juliet of Romeo, concluding that the name of something does not define what it really is. A rose, after all, by any other name would smell as sweet, but for family genealogists, a rose by any other name can become an obstacle to progress and success. Naturally, we go in search of a name as we expect it to be, as we’ve always known it to be and, in doing so – in not considering all the possible variations or that any given spelling may not necessarily be the “correct” spelling – we may overlook vital clues and new pathways for our research. I suspect that most family genealogists who stay at their research beyond the “low hanging fruit” stage, who don’t give up too soon, eventually double back and realize their earlier oversights.

‘What’s in a name?’ asked Juliet of Romeo, concluding that the name of something does not define what it really is. A rose, after all, by any other name would smell as sweet, but for family genealogists, a rose by any other name can become an obstacle to progress and success. Naturally, we go in search of a name as we expect it to be, as we’ve always known it to be and, in doing so – in not considering all the possible variations or that any given spelling may not necessarily be the “correct” spelling – we may overlook vital clues and new pathways for our research. I suspect that most family genealogists who stay at their research beyond the “low hanging fruit” stage, who don’t give up too soon, eventually double back and realize their earlier oversights.

That has certainly been the case with my research. But for dumb luck, a hunch, or unwittingly asking the right questions (or having the right question asked of me), how many of my near misses might have become brick walls of my own doing? Having narrowly avoided a genealogical pitfall, we take a moment to admonish ourselves (DUH) for our “rookie mistake,” and vow never to let it happen again. And yet it probably will, as it has for me.

I quickly learned, in researching my maternal grandfather’s Osborne family, that I should always consider the alternative spelling Osborn.

When I first began genealogy, I did what I suppose most newbies do as a way of establishing a context and a game plan, exploring, however superficially, all of my lines. I quickly learned, in researching my maternal grandfather’s Osborne family, that I should always consider the alternative spelling Osborn. Adding the “e” at the end was, I read, simply a matter of taste within the same family. It turns out that the name can also be spelled Osburn and Osbourne. I now try them all, and then some.

In expanding my maternal grandmother’s tree, I began to learn a little bit about her paternal grandparents, Anthony Giuliani and Agnes Sweeney. I knew that the family name had been changed to Julian (the spelling my grandmother had always used), and the death certificates for both Anthony and Agnes reflected that change. Both were buried in the Old Dorchester Cemetery, now St. Mary’s. Planning my visit, I called ahead only to be told that there was no one in the records with the name Julian. A dead end, I thought, until the woman on the other end of the line asked if I had a burial date that she could cross-reference. Lo and behold, there were Anthony and Agnes, listed under the name Julynn, likely a phonetic version of the name.

Another encounter with variant name spellings occurred after I had travelled with NEHGS a few years ago on a research trip to New Brunswick. During that trip I met one of the archivists at the Provincial Archives in Fredericton and stayed in contact with him after returning home. It appeared that I had hit a brick wall in determining the death date for my great-great-grandfather, Cyprian Downing, who seemed to have disappeared in Moncton sometime before 1893. My new friend was generous enough to keep poking around in the more obscure records and one day he emailed to say that he had hoped to have good news for me but, on second thought, was having doubts. When I asked what he had found, he shared that he had located an 1892 probate record for “Suprine Downie,” in the matter of “Among Levetta Downie.” As I heard myself repeat the names, the jumble of letters seemed to rearrange themselves in my head and it dawned on me that he had, indeed, found a record for Cyprian Downing – whose name is sometimes recorded as Superior – and his daughter, my great-grandmother, Emma Loretta Downing. The probate record provided an exact date for Cyprian’s death as well as other details pertinent to my project. I wondered what might have become of that valuable information if we had not had that conversation.

When I asked what he had found, he shared that he had located an 1892 probate record for “Suprine Downie”...

The Anglicization of names presents another obstacle for researchers. When a friend in Provincetown asked me to research the two gentlemen for whom the Morris-Light American Legion Post #71 is named, I quickly put together a biography for Louis Joseph Morris, born in Truro in 1896 to Joseph Morris, born in Provincetown to Portuguese parents, and Mary Alvernaz Rodgers, born in the Azores. Anticipating an equally smooth process for Anton Light, I came up empty handed. Surely there had to be some record for him, given the service during World War I for which Provincetown had memorialized him. The clue was to be found on the town’s Doughboy monument, where the 1917–1918 Honor Roll shows the name Antonio L. DaLuz. A lightbulb (pun intended) went off. For Provincetown’s record keeping purposes, DaLuz had been Anglicized to Light. Born in Portugal in 1885, DaLuz had served as a boatswain’s mate in the United States Naval Reserve Force. Having survived the sinking of the USS Covington in July 1918, Antonio “Light” was reassigned to the USS Gypsum Queen, a sea-going tug. While rendering assistance off the coast of France, the vessel struck a rock and sank, claiming the lives of fifteen crewmembers, including Antonio Luis DaLuz, who is honored with a star next to his name on the Honor Roll.

The Anglicization of names presents another obstacle for researchers. When a friend in Provincetown asked me to research the two gentlemen for whom the Morris-Light American Legion Post #71 is named, I quickly put together a biography for Louis Joseph Morris, born in Truro in 1896 to Joseph Morris, born in Provincetown to Portuguese parents, and Mary Alvernaz Rodgers, born in the Azores. Anticipating an equally smooth process for Anton Light, I came up empty handed. Surely there had to be some record for him, given the service during World War I for which Provincetown had memorialized him. The clue was to be found on the town’s Doughboy monument, where the 1917–1918 Honor Roll shows the name Antonio L. DaLuz. A lightbulb (pun intended) went off. For Provincetown’s record keeping purposes, DaLuz had been Anglicized to Light. Born in Portugal in 1885, DaLuz had served as a boatswain’s mate in the United States Naval Reserve Force. Having survived the sinking of the USS Covington in July 1918, Antonio “Light” was reassigned to the USS Gypsum Queen, a sea-going tug. While rendering assistance off the coast of France, the vessel struck a rock and sank, claiming the lives of fifteen crewmembers, including Antonio Luis DaLuz, who is honored with a star next to his name on the Honor Roll.

If I was becoming just a little too confident in my ability to recognize a rose by any other name, my comeuppance came not long ago as the finishing touches were being put on a project to identify Revolutionary War veterans buried in Provincetown. Thanks in part to the researchers at NEHGS, the service of seven had been documented and on Patriots’ Day 2018 their graves in the Winthrop Street Cemetery had been appropriately marked. Before retiring the project, I made one last inquiry into three men named Nickerson for whom we had not been able to gather enough documentation to prove Revolutionary War service. In reviewing all my notes, I reflected on the headstone spelling for one of the men, Ebenezer “Nicholson” and, on a hunch, entered that spelling, rather than Nickerson, into the DAR Ancestor database.

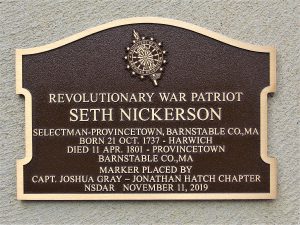

There, right under my nose (DUH, indeed!), was a record for Seth Nicholson (1737–1801), whose service as a Provincetown selectman in 1775 had qualified him as a Revolutionary War patriot. To complicate matters, he was not the Seth Nickerson (1734–1789) I had been researching but, instead, a younger cousin, often referred to as “Short” Seth while the older man was known as “Long” Seth. Another archaic form of distinction between a younger and older man of the same name in the same town refers to them as Jr. and Sr.

Seth Nicholson, aka Nickerson, is also buried in the Winthrop Street Cemetery (his headstone uses the Nickerson spelling), alongside the three other Nickersons but, alas, only he, “Short” Seth, will be honored with a grave marker. What a shame it would have been if his service had been overlooked because of a surname spelling.

Seth Nicholson, aka Nickerson, is also buried in the Winthrop Street Cemetery (his headstone uses the Nickerson spelling), alongside the three other Nickersons but, alas, only he, “Short” Seth, will be honored with a grave marker. What a shame it would have been if his service had been overlooked because of a surname spelling.

What’s in a name? More than might meet the eye, as every genealogist surely has learned the hard way.

Share this:

About Amy Whorf McGuiggan

Amy Whorf McGuiggan recently published Finding Emma: My Search For the Family My Grandfather Never Knew; she is also the author of My Provincetown: Memories of a Cape Cod Childhood; Christmas in New England; and Take Me Out to the Ball Game: The Story of the Sensational Baseball Song. Past projects have included curating, researching, and writing the exhibition Forgotten Port: Provincetown’s Whaling Heritage (for the Pilgrim Monument and Provincetown Museum) and Albert Edel: Moments in Time, Pictures of Place (for the Provincetown Art Association and Museum).View all posts by Amy Whorf McGuiggan →