My sister-in-law Sue and I hoped we might uncover a backstory behind the marriage of her great-great-grandparents. Aimé Vallée, age 21, of St. Casimir, Québec, wed his third cousin, Marguerite Vallée, age 43, widow of François Trottier, mother of twelve children. François died in November 1844, age 69; Marguerite married Aimé three months later, with a dispensation omitting two additional banns of marriage. We sensed our curiosity might be allayed by visiting St. Casimir, midway between Trois Rivières and Québec City. Its splendid late nineteenth-century Catholic church attests to its central place in the life of that community and a long tradition of recording genealogy.

We first consulted several books published by St. Casimir’s genealogical and historical society. Local historians Guy Laviolette and G. Robert Tessier drew heavily on a manuscript history of the parish compiled by its second pastor, Charles-Henri Paquet. Laviolette noted that Père Paquet devoted forty pages of genealogical history to the Vallée family, and by the priest’s own confession, included “too much gossip.”[1] That last phrase had us hooked. On a Saturday morning, we set out for St. Casimir in search of Paquet’s manuscript.

...Père Paquet devoted forty pages of genealogical history to the Vallée family and, by the priest’s own confession, included “too much gossip.”

In retrospect, we might have at least called first before driving four hours from Burlington, Vermont. Arriving in the village, we rang the doorbell of the rectory, where we were greeted by the parish priest. Impressed by Sue’s command of the French language, he acknowledged our interest, retrieved the manuscript from the church safe, and photocopied the relevant 40 pages for us. (Always bring Canadian money for such adventures!) As we read, we immediately gained a more nuanced appreciation of this ultra-Catholic environment. Unsurprisingly, Paquet wrote in a format similar to Québec parish registers in a clear hand and with an unmistakably moralistic point of view.

Marguerite Vallée came from a noteworthy family. Her father, Paul Vallée, from the parish of Ste. Anne de la Pérade, was among the founding families of St. Casimir. A soldier in the War of 1812, he protected his country from the invasion of “Bostonians.” Though he was not wounded in the fighting, Paquet describes Paul’s “bellicose” disposition juxtaposed to the forbearance of his wife.

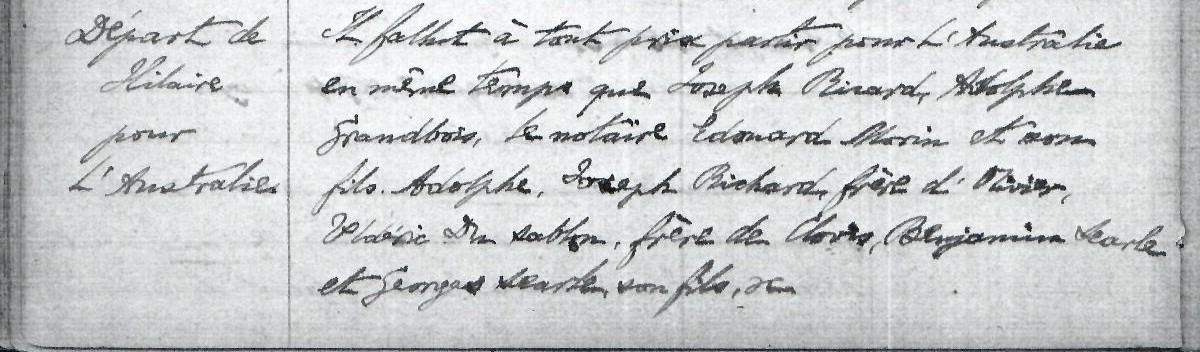

Paquet recounts that the youngest of Paul’s sons, Elie Vallée, had nothing but contempt for village life and sought his fortune in the California Gold Rush. There he committed a mortal sin by marrying an Anglo-Protestant who died three years after their marriage. Elie eventually saw the error of his ways, returned to St. Casimir, and left the church $300 to pray for the repose of his soul. Another of Paul’s sons, Hilaire Vallée, along with several other men from St. Casimir, succumbed to gold fever in Australia – a voyage to the other side of the world. In the 26 years of his absence, Hilaire’s long-suffering wife prayed to St. Raphael for the safe return of her husband. Her prayers were answered, but Hilaire died shortly after coming home.

Compared to the adventures of her brothers, Elie and Hilaire, Marguerite’s life seems tame. In the last weeks of his life, her first husband François Trottier made a will, witnessed by Aimé Vallée, leaving all his wordly goods to Marguerite for the support of their children. The unromantic truth is, that in this environment, Marguerite would not have managed without a husband. Perhaps Aimé entered this marriage, with the blessing of the priest, as a way of keeping a roof over Marguerite’s head and feeding her children. Nonetheless, two years after they married, Marguerite gave birth to one last child, Hermidas Vallée, Aimé’s only son.

The unromantic truth is, that in this environment, Marguerite would not have managed without a husband.

Their multi-generational household, with Marguerite’s eldest son only three years younger than his step-father, undoubtedly had its tensions. As land records reveal, Aimé struggled to support such a large family, and Marguerite had to sell much of the property François Trottier left to her. Aimé, in time, found it more profitable to earn a living as a baker than as a farmer. Aimé and Marguerite’s son Hermidas married at 17, fathered thirteen children by two wives, and lived under the same roof with his parents. Aimé’s last years were marred by the tragic death of Hermidas, age 49, who fell into a blade at the local saw mill, severing him in two—his body was brought home in a basket. How his family rebounded will be the subject of my next posting.

In our successful quest for deeper knowledge of our ancestors, Sue and I were reminded of how much of Québec’s ancestral heritage has been preserved by parish priests — from the Jesuits of the seventeenth century, to the work of Cyprien Tangué and the anecdotal history of Charles-Henri Paquet. And there’s the joy in discovering unique, on-site source material.

Continued here.

Note

[1] Bavardage. All sources consulted are written in French.

Share this:

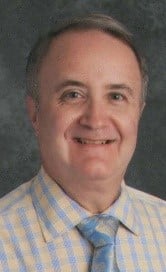

About Michael Dwyer

Michael F. Dwyer first joined NEHGS on a student membership. A Fellow of the American Society of Genealogists, he writes a bimonthly column on Lost Names in Vermont—French Canadian names that have been changed. His articles have been published in the Register, American Ancestors, The American Genealogist, The Maine Genealogist, and Rhode Island Roots, among others. The Vermont Department of Education's 2004 Teacher of the Year, Michael retired in June 2018 after 35 years of teaching subjects he loves—English and history.View all posts by Michael Dwyer →