A time of major transition – I just retired from teaching after a wonderful run of thirty-five years. No one who knows me well asks: What will you do [more of] next? While genealogy, per se, was not part of the prescribed English and history curriculum, that quest always played in the background and sometimes assumed center stage. Particularly in the teaching of American history, it became the hook which anchored students to a personalized past.

Every Thanksgiving, I would manage to sneak in a lesson on William Bradford, my great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, that usually began with a recitation from Of Plimoth Plantation, committed to memory: “It is well known unto the godly and judicious…” What impressed my students more than a hearty declamation of the text was that I could recount my descent from Bradford. During my first year of teaching, when seniors just a few years younger than I sorely tried me, one student stayed after class to talk to me. “Don’t tell my friends I told you this, but I am a descendant of John Alden. Have you heard of him?”

His secret remained safe with me for the short term. Fast forward twenty-years: A friend volunteered me for a WCAX news story on how some local Mayflower descendants spend Thanksgiving. The film crew first came to school to interact with a couple of my students who had ties to the Pilgrims. How times had changed! Ian, a junior, thought it was cool to be related to his teacher. On Thanksgiving Day, my family, however, was slightly apprehensive while the cameras filmed our turkey dinner.

Another meaningful episode of early teaching days occurred when I asked students to investigate an immigrant ancestor to Rutland County, Vermont. That assignment, long before the emergence of the internet, required students to conduct live interviews with older relatives. Two of my juniors just did not like each other. Jim presented his report first: “My immigrant ancestor was Bridget Gillfeather of West Rutland.” Farrell jumped up: “You copied my paper!” It did not take me long to ascertain the obvious. “Farrell, meet your cousin Jim. Jim, meet your cousin Farrell.”

Many of my Vermont students have French-Canadian ancestry, often obscured through names directly translated, like Shortsleeves for Courtemanche, or others somehow garbled: Benware instead of Benoit. Thelma Bosley liked me much better after I revealed her original name as Beausoleil, “beautiful sunshine.”

Their assertion revolved around a story passed down about a great-great-grandmother, with dark hair or high cheek bones, who belonged to a certain tribe, etc.

The most recurrent research request among my students and their families: to find their Native American ancestors. Their assertion revolved around a story passed down about a great-great-grandmother, with dark hair or high cheek bones, who belonged to a certain tribe, etc. In almost every instance, these stories proved untrue. For senior Ashlee Bird, a consolation discovery was learning her Quebec-born ancestor, Edward Bird, a Vermont Civil War veteran, had been baptized as Antoine Loiseau – first and last names transformed.

In assisting my students to discover an immigrant grandparent, no matter how many generations removed, we go beyond filling out names on a pedigree chart to connect individuals to the larger forces that shaped their lives. In prefacing a unit on World War I, I asked students if anyone in their family had a connection to the conflict. Hunter, a junior, said a World War I helmet sat on his father’s television set, and he thought “it belonged to someone in the family.”

With a snippet of information from Hunter the next morning, I said that I would search during lunch. Lunch had hardly begun when Hunter asked me if I found anything.“Give me another ten minutes,” I said. When I printed Hunter’s great-great-grandfather’s World War I draft registration, Hunter displayed it in the plastic cover of his loose-leaf notebook for the rest of the year. Several weeks later, during parent conferences, Hunter’s father asked me, “What have you done to my kid?” He added that while he and Hunter were running errands on the other side of Vermont, Hunter had said, “Dad, can we stop at the cemetery up the road? I want to see if there is a World War I marker on your great-grandfather’s grave.”

Ripples in the pond will continue long after my departure from the classroom. If I were to give advice to any aspiring history teacher, I would say: “Teach not only significant content on how our nation’s history has shaped the present, but also inspire your students with the tools to continue the discovery, over a lifetime, of the past lives of their own ancestors.”

Share this:

About Michael Dwyer

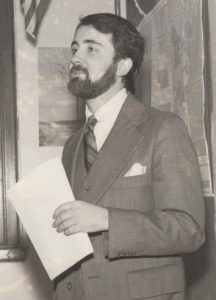

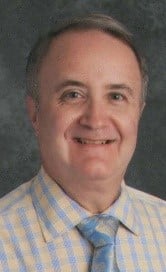

Michael F. Dwyer first joined NEHGS on a student membership. A Fellow of the American Society of Genealogists, he writes a bimonthly column on Lost Names in Vermont—French Canadian names that have been changed. His articles have been published in the Register, American Ancestors, The American Genealogist, The Maine Genealogist, and Rhode Island Roots, among others. The Vermont Department of Education's 2004 Teacher of the Year, Michael retired in June 2018 after 35 years of teaching subjects he loves—English and history.View all posts by Michael Dwyer →