Samuel Parkman house, Bowdoin Square, Boston, by Philip Harry, 1847. R. Stanton Avery Special Collections

Samuel Parkman house, Bowdoin Square, Boston, by Philip Harry, 1847. R. Stanton Avery Special Collections

Among the many treasures in the Society’s collection is an extraordinarily well-preserved circa 1847 oil painting by Philip Harry of a grand Boston home that no longer exists: the late eighteenth-century Samuel Parkman House on Bowdoin Square in the West End.

Founded in 1788, Bowdoin Square had, by the early nineteenth century, become one of the most prestigious residential areas of the city and home to many of Boston’s leading families, including the Parkmans. (Samuel Parkman, who built the house around 1789, was a successful merchant who made a fortune in real estate as Boston grew into one of the most important cities in the new republic.)

Sadly, as the nineteenth century progressed, Bowdoin Square became increasingly run-down – an area noted more for its boarding houses and snake oil salesmen than its majestic houses. With the exception of the Harrison Gray Otis House (Boston’s only extant free-standing eighteenth-century townhouse, now a world-class house museum owned by Historic New England), all of the great private houses, including the Samuel Parkman House, were demolished.

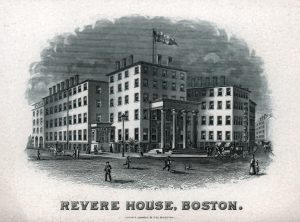

With the loss of so much of the West End, the NEHGS painting of the Parkman House transforms from a lovely scene to a valuable record of lost Boston. And there’s more than just the documentation of a demolished house in this painting – to the right of the house is a corner of Bowdoin Square Baptist Church, a site occupied today by the circa 1930 New England Telephone & Telegraph Company building. In the bottom right corner are two African American porters (an extraordinarily rare depiction of African Americans in a nineteenth-century painted view of Boston) from the nearby Revere House, one of Boston’s most prestigious mid-nineteenth-century hotels. Named after the famous Paul Revere, this luxurious Bowdoin Square hotel hosted many of the luminaries of the day, including Charles Dickens, Walt Whitman, Ulysses S. Grant, and the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII of Great Britain). Top it all off, the celebrated Daniel Webster (who was a member of NEHGS!) used the hotel’s portico to address crowds at political rallies!

With the loss of so much of the West End, the NEHGS painting of the Parkman House transforms from a lovely scene to a valuable record of lost Boston. And there’s more than just the documentation of a demolished house in this painting – to the right of the house is a corner of Bowdoin Square Baptist Church, a site occupied today by the circa 1930 New England Telephone & Telegraph Company building. In the bottom right corner are two African American porters (an extraordinarily rare depiction of African Americans in a nineteenth-century painted view of Boston) from the nearby Revere House, one of Boston’s most prestigious mid-nineteenth-century hotels. Named after the famous Paul Revere, this luxurious Bowdoin Square hotel hosted many of the luminaries of the day, including Charles Dickens, Walt Whitman, Ulysses S. Grant, and the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII of Great Britain). Top it all off, the celebrated Daniel Webster (who was a member of NEHGS!) used the hotel’s portico to address crowds at political rallies!

The story of the Parkman family is an inspiring and tragic one. Samuel’s son, Dr. George Parkman, became one of the leading lights of Boston. He endowed the Parkman Professorship of Anatomy and Physiology at Harvard (his alma mater) and donated a large piece of land in the West End to build Harvard Medical School – home today of the world-famous Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr. Parkman’s friend, John James Audubon, even named a bird – the Parkman Wren (Troglodytes Parkmanii) – after him.

It all came to an ugly end when George was murdered and dismembered in 1849 by Dr. John White Webster. The murder was one of the most sensational events of nineteenth-century Boston and rapidly became an international event via the fast-growing popular press. Ironically, Dr. Parkman was murdered at Harvard Medical School, built on the land he donated to the university. The city was rocked to the core and the Parkman family never recovered (they lived as recluses for the rest of their lives). Like so much art adorning the Society’s walls, this painting is both beautiful and historical, and it gives us a link to Boston’s rich and vibrant past.

Share this:

About Curt DiCamillo

Curt is American Ancestor’s Curator of Fine Art. As part of the Education team, he curates American Ancestors’ large art collection, lectures around the world, and hosts the celebrated American Ancestors Art & Architecture webinar series. Curt liaises with all American Ancestors teams and regularly engages with members and donors around the world through the scholarly tours he leads for American Ancestors to Europe and America. Before he came to American Ancestors in 2016, Curt was the CEO of the National Trust for Scotland USA and, before that, the manager of the conservation department of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, where he worked for 13 years. In 2024 American Ancestors published Curt’s latest book, A British Country House Alphabet: A Historical & Pictorial Journey. Published to international acclaim, the first volume (in a series of three) features stories that will enchant seasoned country house visitors—and entertain those new to art and architecture—as they read about surprising snippets of history that occurred at, or because of, a country house in England, Scotland, or Wales. Curt’s previous book, Villa Astor: Paradise Restored on the Amalfi Coast, was published in 2017 by Flammarion. Curt has been presented to Charles, the Prince of Wales, and the late Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother in recognition of his work on British country houses.View all posts by Curt DiCamillo →