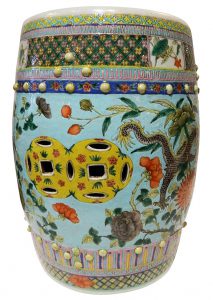

The New England Historic Genealogical Society is rediscovering many treasures within its Atkinson-Lancaster Collection, an eclectic assemblage of art that came to the Society in 1933 from the Atkinson family of Newburyport, Massachusetts. The Atkinsons made their fortune in the nineteenth-century India trade. We’ve just rehung the Treat Rotunda (Figure 1) with pieces from the collection, including two lovely celadon-and-cream-colored nineteenth-century Chinese garden seats (Figure 2, below).

Garden seats are found all over the world, but usually as decorative arts objects in interior spaces. They were, of course, originally developed as a comfortable place to sit while gardening, and were made of material (usually porcelain) that could stand up to all kinds of weather. They are always hollow, and open at the bottom, to allow water to drain.

The Atkinson family probably acquired our two garden seats when they lived in India in the 1850s. (You can see a photo of the family’s Calcutta villa above in Figure 3.) They may even have been used for gardening while in India! These gardens seats are a bit different than the norm because of their fretwork and unusual colors. The more commonly-seen version is polychrome, with traditional Chinese designs and characters, as in Figure 4 (at right).

Of course, other countries made (and still do make) porcelain garden seats, especially the English potteries. The set of nineteenth-century Minton blue-and-white garden seats in Figure 5 is a perfect example of the British blending of Asian and European design elements: the slit in the middle allowed water to drain, and also provided an easy way to pick up and move the seat.

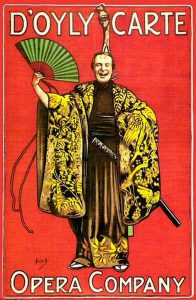

The popularity of garden seats during the 1800s was part of an explosion of interest for all things Asian (or, as Europeans would have said at the time, Oriental). This Asian curiosity reached a crescendo late in the century, as evidenced by the immense popularity of Gilbert & Sullivan’s operetta, The Mikado, which opened to great acclaim in London in 1885 (Figure 6).

The romance and beauty of Asian art was also a cornerstone of the Aesthetic Movement. This movement, of which Oscar Wilde was a key mover and shaker, valued beauty for its own sake and was obsessed with blue-and-white porcelain. (In Wilde’s famous lecture of 1882, entitled The House Beautiful, the famous wit and author said it wasn’t possible to have a beautiful home without Oriental art, or blue-and-white, porcelain.)

Boston and London were the leading centers for the movement and many a Beacon Hill townhouse was furnished in the Aesthetic style (Figure 7 shows an idealized Aesthetic interior in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), which included a plethora of porcelain garden seats!

Figure 8. This image is licensed through the Smithsonian's Freer and Sackler Galleries under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license

Figure 8. This image is licensed through the Smithsonian's Freer and Sackler Galleries under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license

Possibly the finest example today illustrating the successful merging of Asian and European art into an Aesthetic whole is by the American artist James McNeill Whistler, who grew up in Lowell, Massachusetts. His famous Peacock Room, formally Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room (Figure 8), was painted between 1876 and 1877 for the British shipping magnate Frederick Richards Leyland. It was installed in Leyland’s house in the Kensington section of London, and is considered one of the greatest surviving Aesthetic interiors: possibly the finest example in the world of the Anglo-Japanese style. The room is today in The Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., where its amazing blending of Asian and European art still stuns with Aesthetic intensity. And, of course, the Peacock Room is studded with blue-and-white porcelain!

You can see the Society’s Chinese garden seats, as well as other pieces from the Atkinson-Lancaster Collection, Tuesday through Saturday in the Treat Rotunda on the first floor of our Newbury Street building in Boston.

Share this:

About Curt DiCamillo

Curt is American Ancestor’s Curator of Fine Art. As part of the Education team, he curates American Ancestors’ large art collection, lectures around the world, and hosts the celebrated American Ancestors Art & Architecture webinar series. Curt liaises with all American Ancestors teams and regularly engages with members and donors around the world through the scholarly tours he leads for American Ancestors to Europe and America. Before he came to American Ancestors in 2016, Curt was the CEO of the National Trust for Scotland USA and, before that, the manager of the conservation department of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, where he worked for 13 years. In 2024 American Ancestors published Curt’s latest book, A British Country House Alphabet: A Historical & Pictorial Journey. Published to international acclaim, the first volume (in a series of three) features stories that will enchant seasoned country house visitors—and entertain those new to art and architecture—as they read about surprising snippets of history that occurred at, or because of, a country house in England, Scotland, or Wales. Curt’s previous book, Villa Astor: Paradise Restored on the Amalfi Coast, was published in 2017 by Flammarion. Curt has been presented to Charles, the Prince of Wales, and the late Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother in recognition of his work on British country houses.View all posts by Curt DiCamillo →