[Editor's note: This blog post originally appeared in Vita Brevis on 12 November 2014.]

While writing my blog focusing on archaic medical terms a few months ago, I began thinking about other aspects of everyday life that appeared in records used by genealogists. One element of an individual’s life which appeared on everything from wills to land deeds to town records was occupation. While some of the occupations listed on records throughout the last four hundred years still exist today (farmers, blacksmiths, and wood workers, to name a few), many of these jobs either are known by a different name or are entirely obsolete in modern society.

Despite this, knowing the meaning behind these occupational titles can provide researchers with not only a sense of a forebear’s lifestyle but can also help answer some key questions, including:

While writing my blog focusing on archaic medical terms a few months ago, I began thinking about other aspects of everyday life that appeared in records used by genealogists. One element of an individual’s life which appeared on everything from wills to land deeds to town records was occupation. While some of the occupations listed on records throughout the last four hundred years still exist today (farmers, blacksmiths, and wood workers, to name a few), many of these jobs either are known by a different name or are entirely obsolete in modern society.

Despite this, knowing the meaning behind these occupational titles can provide researchers with not only a sense of a forebear’s lifestyle but can also help answer some key questions, including:

- What was their financial situation?

- What was their standing in the community?

- Were certain skills and trades considered part of a family tradition?

Perhaps the most common occupation seen on land records and other documents is ‘yeoman.’ Yeomen were farmers who owned their own land instead of renting it or working on land owned by another individual.[1] In the early years of American history, land was often readily available and families had to grow their own food in order to survive, resulting in yeomanry being among the most commonly cited occupations.

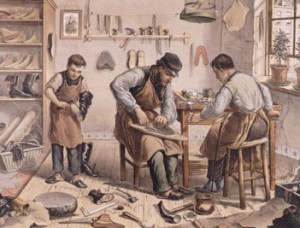

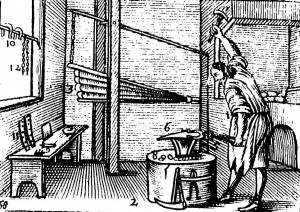

Other occupational terms are no longer in use, but these terms applied to jobs which still exist today. For instance, a cordwainer,[2] known today as a cobbler or shoemaker, was a surprisingly popular occupation, as cordwainers also tended to work in the construction of other leather goods. A Vulcan was another term for a blacksmith, who was a critical element of a successful community, as farming tools and weaponry were always in high demand.[3] Other terms no longer in use today included housewright (a builder of houses) and lagger (a sailor).[4]

Other occupational terms are no longer in use, but these terms applied to jobs which still exist today. For instance, a cordwainer,[2] known today as a cobbler or shoemaker, was a surprisingly popular occupation, as cordwainers also tended to work in the construction of other leather goods. A Vulcan was another term for a blacksmith, who was a critical element of a successful community, as farming tools and weaponry were always in high demand.[3] Other terms no longer in use today included housewright (a builder of houses) and lagger (a sailor).[4]

Interestingly, there are some occupations which, despite their archaic nature, still exist in small towns, particularly in New England. While these positions are sometimes regarded as honorary and exist only in a symbolic capacity, others jobs still involve performing the same tasks and are a part of town records. One such position in the latter category is the hog reeve, a title given to the person responsible for preventing and assessing the damage caused by stray hogs.[5] In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, if a domestic swine escaped from its enclosure and caused damage to a neighbor’s crops, there could be serious implications. In the twenty-first century, such threats are minimal at best. In spite of this, as recently as 2006 the town of Grantham, New Hampshire, maintained the title of hog reeve, and while the position is unpaid, it remains a part of the town’s local history.[6]

The fence viewer is another position that, in many parts of the country, time has forgotten; it still exists in New England and the Midwest. A fence viewer is an individual in charge of inspecting new fences and settling disputes which arise as a result of trespassing livestock. In Massachusetts, the first fence viewer was installed in 1693, and in many towns they are still selected by the Board of Aldermen or the Mayor.[7] Fence viewers are asked to advise lot owners who intend to construct a fence on their property.[8] The State of Vermont takes the position of fence viewer even more seriously, devoting an entire chapter of statutes to the position. In order to ensure that the position is respected and the holder completes their duties, Chapter 109, Statute 3810 of the Vermont Constitution reads:

“If a fence viewer neglects to perform the duties required of him or her, he or she shall forfeit to the party aggrieved $5.00, with costs to be recovered in an action of tort on this statute.”[9]

As one can imagine, this statute was likely developed at a time when fence viewing was a more critical part of life in small communities across America. (Nebraska’s legislature dealt with matters regarding fence viewers as recently as 2007.[10]) While these titles have largely become a formality in the twenty-first century, they were important enough in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries to be mentioned in town records and in other records which are critical to the work of genealogical researchers. An awareness of these positions and the duties they entailed allow for a greater understanding of how they shaped our ancestors’ roles in their communities.

Notes

[1] Rodney Hall, Hall Genealogy Website, updated 22 September 2009. <http://rmhh.co.uk/occup/x-z.html#Y>.

[2] A List of Occupations, Rootsweb, <http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~usgwkidz/oldjobs.htm>.

[3] A List of Occupations, Rootsweb, <http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~usgwkidz/oldjobs.htm>.

[4] A List of Occupations, Rootsweb, <http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~usgwkidz/oldjobs.htm>.

[5] Janice Brown, “New Hampshire Glossary: Hog Reeve,” Cow Hampshire, 8 April 2006 <http://www.cowhampshireblog.com/2006/04/08/new-hampshire-glossary-hog-reeve/>.

[6] Sonia Scherr, “This town has hog reeves . . . but not a hog in sight,” Concord Monitor, 22 March 2007 <http://www.concordmonitor.com/article/this-town-has-hog-reeves-but-not-hog-in-sight>.

[7] Town of Cummington, Massachusetts, “Annual Report For The Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 2013” <http://www.cummington-ma.gov/SiteAssets/Docs/Town/TownReportFy2013.pdf>.

[8] Len Dalton, “The Melrose Fence Viewer,” The Melrose Mirror, 4 August 2000 <http://melrosemirror.media.mit.edu/servlet/

pluto?state=3030347061676530303757656250616765303032696430303434313033>.

[9] The Vermont Statutes Online, Title 24: Municipal and County Government, Chapter 109: Fences and Fence Viewers.

[10] Dave Aiken, “LB108 Repeals Fence Viewer Process,” Cornhusker Economics, Institute of Agriculture & Natural Resources, Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Nebraska–Lincoln, 7 March 2007.

Share this:

About Zachary Garceau

Zachary J. Garceau is a former researcher at the New England Historic Genealogical Society. He joined the research staff after receiving a Master's degree in Historical Studies with a concentration in Public History from the University of Maryland-Baltimore County and a B.A. in history from the University of Rhode Island. He was a member of the Research Services team from 2014 to 2018, and now works as a technical writer. Zachary also works as a freelance writer, specializing in Rhode Island history, sports history, and French Canadian genealogy.View all posts by Zachary Garceau →