There has always been some secrecy surrounding the Heisinger side of my family. My grandfather did not know anything about his paternal grandfather, Charles Heisinger, because my great-grandfather, Walter Heisinger, never spoke of his father. We were not even sure of his first name, only that we all had inherited the Heisinger surname from a mystery man. Undoubtedly there was some painful history that my great-grandfather did not wish to share with his children, but it left us with a hole in our family history.

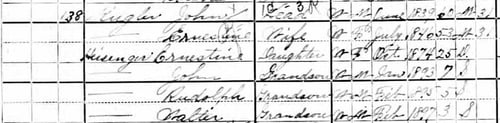

John Kugler Household, 1900 U.S Federal Census, Brooklyn Ward 28, Kings, New York; Roll 1066; Page 7A; Enumeration District 0502, accessed at familysearch.org.

John Kugler Household, 1900 U.S Federal Census, Brooklyn Ward 28, Kings, New York; Roll 1066; Page 7A; Enumeration District 0502, accessed at familysearch.org.

When I began researching the Heisinger side of the family, the earliest record I could locate for Walter was the 1900 U.S. Federal Census, when he was 3 years old living in the household of his grandparents, John and Ernestine Kugler, in Brooklyn, New York. Also in the household were Walter’s mother, recorded as Ernestine Heisinger, and Walters’s two older brothers, John (Jean) and Rudolph. Ernestine Heisinger was recorded as divorced. Locating this record helped explain why Walter never spoke of his father, if they were no longer living together when Walter was so young— but it did not help me to identify his father.

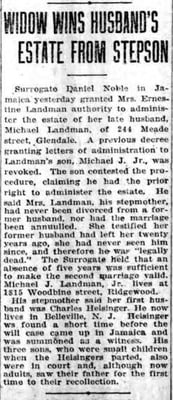

Tracing the family forward, I discovered that Ernestine (Kugler) Heisinger later remarried a man named Michael Landman. It would be this information that eventually led me to identifying Walter’s father. A newspaper article in The Brooklyn Standard Union on 19 December 1920 reported that Ernestine Landman, widow of Michael Landman, was granted the authority to administer her late husband’s estate after her stepson had contested her right, claiming that she had never divorced her first husband. The article mentioned that Ernestine’s first husband was summoned as a witness in the case, and that it was the first time Walter or his brothers had seen their father since he abandoned the family twenty years earlier. His name: Charles Heisinger. Finally!

With his name, I was able to track down and order the marriage record for Charles Heisinger and Ernestine Kugler from the New York City Department of Health. I discovered they were married in Brooklyn, on 27 March 1892. Luckily, the marriage record contained a wealth of information about both Ernestine and Charles. I learned that Charles’s full name was Karl Frederick Wilhelm Heisinger, that he was 25 years old at his marriage, and that he was born in New York City. Even more exciting, the groom's parents' names on the record enabled me to take the Heisinger line back another generation to Karl and Henrietta Heisinger, who immigrated to New York from Prussia in 1861.

After many years of wondering, I now know where my maiden name came from, and I have a better sense of the trials and tribulations that created the gap in my family’s history. I also can understand why my great-grandfather never spoke of his father. In my journey to find Charles Heisinger, I see how family history findings can both humanize our ancestors and maybe even help heal the pains of the past.

Share this:

About Meaghan E.H. Siekman

Meaghan joined the American Ancestors staff in 2013 as a Researcher before moving to the Publications team in 2018 where she is currently a Senior Genealogist of the Newbury Street Press. As a part of the Publications team, Meaghan researches and writes family histories and other scholarly projects. She also regularly develops and presents lectures as well as other educational material on a variety of research topics. Additionally, Meaghan serves as the American Ancestor's representative to the New England Regional Fellowship Consortium. Meaghan holds a PhD in history from Arizona State University where her focus was public history and American Indigenous history. Prior to joining American Ancestors, she worked as Curator of the Fairbanks House in Dedham, Massachusetts and as an archivist at the Heard Museum Library in Phoenix. Meaghan also worked for the National Park Service and wrote several Cultural Landscape Inventories, most notably for Victoria Mine within the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Her doctoral dissertation, Weaving a New Shared Authority: The Akwesasne Museum and Community Collaboration Preserving Cultural Heritage, 1970-2012, explored how tribal museum utilized shared authority with their communities. For American Ancestors, Meaghan authored Ancestry of Secretary Lonnie G. Bunch II in 2023, and Ancestry of Douglas Brinkley in 2019. She co-authored with Chistopher C. Child, Family Tales and Trials: Settling the American South in 2020. She also contributed to Ancestors of Cokie Boggs Roberts with Kyle Hurst in 2016. She has published portable genealogists on African American Genealogy (2015) and Native Nations in New England (2020). Meaghan has authored several articles in her tenure for American Ancestors magazine including most recently, “10 Myths about Slavery in the United States.” She has presented many lectures on African American genealogy, researching enslaved ancestors, researching the history of a house, using oral history in genealogical research, researching women, and other topics.View all posts by Meaghan E.H. Siekman →