A great way to begin tracing your family history is to interview living relatives, asking for relevant birth, marriage, and death information. These interviews sometimes yield specific information (or at least an estimate), and you can then contact the appropriate authority to provide a copy of the original vital record.

But what do we do if grandma’s information fails to lead us to a vital record? Surprisingly, this is more common than you’d think, as people often misremember facts or were told the wrong information from the get-go. In this case, grandma may lead us on a wild goose chase trying to track down the correct location and/or date of a vital record. This may be especially annoying if the record is more recent, as statewide indexes for modern vital records are less common. To locate these modern vital records (civil records), we must first look for an alternative record to point us in the right direction. Here are some examples:

- U.S. Federal Census or state census. While census records often include birth and marriage information in terms of ages (e.g., how old were you at your first marriage?), they can provide enough information to determine when and where an event occurred. For example, if a person disappears from the census, or the spouse is listed as a widow, he or she may have died between enumerations.

- Social Security Death Index. The SSDI is the closest researchers come to a national U.S. death index (even though each state complies with the index differently). The index provides an exact birth date, as well as the month and year of death. Using this record group, you may also want to order your recent ancestor’s Social Security Application (SS-5), which will include parents’ names and employer information. (See “Tips for using the Social Security Death Index.”)

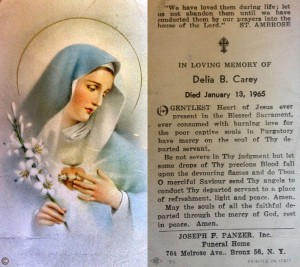

- Funeral prayer cards. My grandmother has a collection of these prayer cards, which gave me information about the death of several people, including my great-grandmother, Delia Bridget Carey. To locate funeral prayer cards, check with other family members, as well as local libraries, archives, and historical societies. (NEHGS has some funeral prayer cards in the R. Stanton Avery Special Collections.)

- Newspapers. Birth notices, marriage announcements, and obituaries are often printed in the newspaper. Several sites have large collections of digitized newspapers, such as GenealogyBank, Newspaperarchive.com, Newspapers.com, Google News Archive, and the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America Collection. To locate local newspapers, check with the local library.

- School records. Yearbooks, class books, and alumni directories often include personal information about students, such as their birth dates and spouses’ names. NEHGS maintains a large collection of class books for Harvard and Yale, as well as other colleges and universities; Ancestry.com has a database of U.S. school yearbooks from 1800 to 2012.

- Membership cards/applications. From the Masons to the DAR, membership cards/applications often provide specific information about their supporters. If your ancestor belonged to a society, you should research whether the organization maintained membership records.

- Bank or insurance records. Follow the money! If your ancestor invested, or held a bank account, his or her birth, marriage, or death information may be included in the records of that institution. For example, the records of the Massachusetts Catholic Order of Foresters (MCOF) contain a wealth of information, including the names of the insured’s children and parents.

These are just a few of the modern alternatives; many more exist. Tomorrow I will outline some of the common vital record alternatives for older generations, such as probate records and cemetery stones. Don’t forget to tune in!

Share this:

About Lindsay Fulton

Lindsay Fulton is a nationally recognized professional genealogist and lecturer who joined American Ancestors in 2012. She leads the Research and Library Services team as Chief Research Officer, as well as the research team working on 10 Million Names. In addition to helping constituents with their research, Lindsay has authored a Portable Genealogists on the topics of Applying to Lineage Societies and the United States Federal Census (1790-1950), and is a frequent contributor to the American Ancestors blog, Vita-Brevis. She was featured in the Emmy-Winning Program: Finding your Roots: The Seedlings, a web series inspired by the PBS series “Finding Your Roots with Henry Louis Gates, Jr.", as well as another popular PBS series, “Samantha Brown’s Places to Love.” Before, American Ancestors, Lindsay worked at the National Archives and Records Administration in Waltham, Massachusetts, where she designed and implemented an original curriculum program exploring the Chinese Exclusion Era for elementary school students. She holds a B.A. from Merrimack College and M.A. from the University of Massachusetts-Boston. Area of Expertise: State and Federal Censuses, New England, Ireland, and New York research, with a focus on research methodology and organization. Lindsay also oversees the research team working on the 10 Million Names project.View all posts by Lindsay Fulton →