Do you have an ancestor from New Hampshire who was working at sea at the young age of 10 or 12? Have you seen a U.S. Federal Census record that states that your ancestor was a “mariner” at age 13? Did you think it was a mistake or an oversight? In fact, many boys as young as 10 were working on ships in New Hampshire in the late 1700s and early 1800s.

After the close of the Revolutionary War, shipbuilding and commerce along the Piscataqua River in New Hampshire flourished. The merchants and traders of the ports along the river were quick to profit because they were no longer subject to direct British restraint. This was in stark contrast to earlier times as Portsmouth, New Hampshire, did not own a single square-rigged vessel in seaworthy condition before the close of the war.[1]

Ships, brigs, and schooners were constantly loading and discharging cargoes at the various wharves along the Piscataqua and Cochecho Rivers in New Hampshire. Outgoing cargo included fish, lumber, beef, and pork, plus live animals such as horses, mules, oxen, sheep, pigs, chickens, geese, and turkeys. The ships also traded and sold swords, guns, spyglasses, and other wares made locally. The ships returned from far-off locales bearing molasses, sugar, wine, and “sundry European goods.”[2]

There were also localized river traffic and occupations involving shipping in New Hampshire. From 1783 through the 1820s, many stores selling various goods opened along the waterfronts. Local trading was augmented during this time, and gundalows and packets plied the waters daily on scheduled runs to and from Maine and Massachusetts, delivering both freight and passengers to various destinations along the coast.[3]

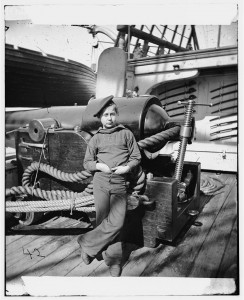

Some ships leaving New Hampshire were not trading ships but rather warships. In 1799 and 1800, the Portsmouth and the Scammel were launched from New Hampshire for the purpose of sailing the West Indies looking to capture French armed ships and to recapture American prizes lost years earlier during the war. Young men on these ships were employed as “powder monkeys,” carrying gunpowder from below deck to the gun deck and artillery pieces, either in bulk or as cartridges, moving with speed and agility.[4] When not in combat, the powder monkeys served as personal assistants to the officers, cook’s helpers, and general helpers for whoever needed them, assigned to whatever odd jobs needed to be done aboard.[5]

If you are researching your ancestors and come across a 12-year-old who worked as a mariner, remember that the age is not a misprint: working at sea at such a young age was certainly possible in the 1700s and 1800s.

Notes

[1] William G. Saltonstall. Ports of Piscataqu: Soundings on the Maritime History of Portsmouth, N.H. (New York: Russell & Russell, 1941), p. 118.

[2] Saltonstall. Ports of Piscataqua, p. 142.

[3] Robert A. Whitehouse and Cathleen C. Beaudoin, Port of Dover: Two Centuries of Shipping on the Cochecho (Portsmouth, N.H.: Portsmouth Marine Society, 1988), p. xii.

[4] J. Arthur Moore, “Powder Monkey and Ship’s Boy,” website of Up from Corinth: Journey into Darkness, at upfromcorinth.com/blog/powder-monkey-and-ships-boy-2.

[5] Brian Lavery, Nelson’s Navy: The Ships, Men, and Organization, 1793–1815 (Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1989), p. 88.

Share this:

About Andrew Krea

Andrew Krea holds a B.A. in English Literature from Brandeis University, in Waltham, Massachusetts, and a Master’s Degree in Library Science from Simmons College in Boston, Massachusetts. He has previously interned at the Massachusetts Historical Society. His areas of interest and expertise include New England research, specifically genealogies dating back to the inception of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and researching and writing historical narratives of family genealogies.View all posts by Andrew Krea →