Many of us have been betrayed, genealogically speaking, by a source that appears to be reliable but is not. Often the source is reliable for the most part. But that fact gives you no comfort when the information in which you are interested turns out to be incorrect.

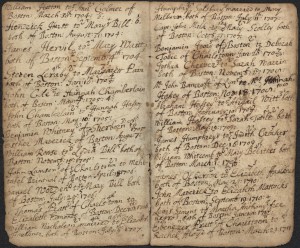

This is why we insist that every statement that is not common knowledge be cited to one or more reliable sources. For example, when working on a colonial Boston family, you should use the Thwing Index (Annie Haven Thwing, Inhabitants and Estates of the Town of Boston, on CD-ROM). However, take the time to look at the original documents cited. Many of her abstracts are faulty, particularly for wills, and her genealogical conclusions are not always correct, especially when there was more than one person of the same name.

Another example is a basic source for colonial New York, the seventeen volumes of Abstracts of Wills, published by the New-York Historical Society. It is essential to look at the original will libers on microfilm and/or the original wills (many of which have survived and are at the State Archives in Albany). The early volumes of abstracts especially are riddled with mistakes, some major, that are not corrected in the last two volumes.

Sometimes long-repeated connections that look good have made their way into compiled reliable sources. For example, the long-standing claim that Ann, wife of Thomas2 Pell of Westchester County, New York, was the daughter of Wampage, a local Indian chief, has been published in two otherwise excellent all-my-ancestors works. However, two Pell descendants have determined that Ann’s origins are unknown, although their article has not yet been published.

Often the betrayal is of our own making. We rely on a source to be complete and it isn’t. For example, the Barbour Collection of Connecticut Vital Records does not cover all the towns in Connecticut or even all the records of the towns it includes — yet it is easy to forget these caveats and assume no record exists of a particular birth, marriage, or death. (See, for example, Chris Child’s recent blog post on identifying Sally Latimer Goold.) Or we cite an index as a source, and later find out we were not quite right. An important example of this is Torrey’s New England Marriages Prior to 1700. Torrey intended this only as a finding aid for researchers to consult the sources he cited and draw their own conclusions.

The moral of the story is to look for original records whenever possible — and be aware of the limitations of the sources you consult.

Share this:

About Henry Hoff

Henry Hoff is Editor of the New England Historical and Genealogical Register and is a Fellow of the American Society of Genealogists as well as a Fellow of the New York Genealogical and Biographical Society. He is also a Certified Genealogist. His genealogical interests include New York and the West Indies. Henry is the author of more than 125 genealogical articles in numerous scholarly journals and is the co-author, compiler, or editor of seven books.View all posts by Henry Hoff →