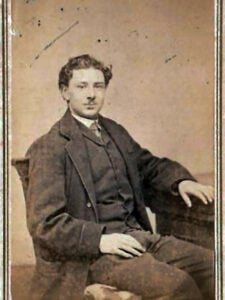

Observance of Memorial Day always compels me to think about the members of my extended family from Block Island who served in the Civil War, and the long-term effects of the war on their lives. This carte-de-visite photo of eighteen-year-old George Albion Paine, taken in the spring of 1866, belies his turbulent experiences.1

Observance of Memorial Day always compels me to think about the members of my extended family from Block Island who served in the Civil War, and the long-term effects of the war on their lives. This carte-de-visite photo of eighteen-year-old George Albion Paine, taken in the spring of 1866, belies his turbulent experiences.1

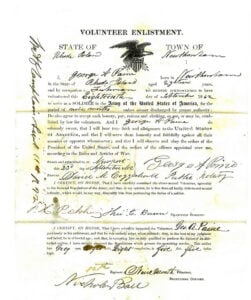

In September 1862, when he was not quite 15, George volunteered to serve for nine months in the 12th Regiment of Rhode Island Volunteers. Patriotic fervor must have swept over the island, because George’s paternal uncle, Alvin Hollis Paine, his maternal uncle Lewis N. Hall, and his uncle-by-marriage, John Thomas, all joined him in the same regiment.2 Barely two months into his service, George was wounded at the Battle of Fredericksburg, spending time in hospital. Comparison with later records shows that George had not yet reached his adult height at this time. He was discharged from the army in July 1863 and re-enlisted in the U.S. Navy, serving as a landsman on ships Savannah and Constitution until discharge in 1866.

Piecing together the rest George’s tumultuous life required years of on-site research, which I conducted in the late 1980s. I learned that George married his first wife Helen Curle Allen in 1869, but soon abandoned her. She filed for divorce on grounds of desertion and later married Charles A. Gilbert. Now spelling his surname as Payne, George became a marketman, and married English-born Margaret Parkinson in New Bedford on 19 December 1876. She died in 1881, age 29. They had one son together, George Rubin Paine, raised in New Bedford by his maternal uncle Jacob Parkinson. There is no surviving evidence that George A. Paine had any interaction with his son after Margaret’s death.

George then returned to Rhode Island once again, where he married divorcée Amelia (Badmington) Powers in 1884. They had a daughter, Gertrude Payne, born the next year in Newport. By the early 1890s, however, Newport City Directories attest that George and Amelia lived at separate addresses. At that point George was working as a house-painter. Newport’s 1903 directory shows that he then moved to Bristol, Rhode Island, where I suspected he lived in the Soldiers’ Home. I checked, and was able to access his personnel files. At first I assumed that this was George’s last stop, but I was surprised to learn that on 14 June 1907, he was chastised for drunkenness and chose to sign himself out. With no subsequent record of a death in Rhode Island, I speculated he may have crossed Mount Hope Bay to Fall River, Massachusetts. My hunch proved true—I found out that he died there of a stroke, two weeks after leaving the home, at only 59 years of age.

On 6 July 1907, a paragraph in Fall River’s The Evening Herald conveyed the sorry circumstances:

“A Veteran Dead. The remains of a veteran of the Civil War lie at the undertaking rooms of J. E. Watson, Jr. on Bank Street. George Payne died at the almshouse Tuesday and no relatives claimed the body.”

Weeks later, Amelia supplied information for the death certificate. No stone marks George’s grave in Fall River’s Oak Grove Cemetery.3 In my middle school years, I would habitually cut through that same cemetery on my walk home—it never occurred to me I could have a relative buried in the same place as the infamous Lizzie Borden!

George’s estranged wife Amelia wasted no time in trying to obtain a Civil War widow’s pension. That process took her almost four years, because she needed to prove that she and George were still married despite years of separation. As Amelia lived until 1945, her pension file was not sent to the National Archives in Washington. It took me some months to track down the file at the Veterans Hospital in White River Junction, Vermont, where I was able to access the original, but was not allowed to photocopy any part of it.4

Through obituaries and telephone directories, I tracked down Amelia and George’s only granddaughter: Gwendolyn Crutchfield, who lived in North Carolina. We had a brief phone call, during which she told me, “I have no interest whatsoever in learning anything about my grandfather, George.” Gwendolyn died in 1990, leaving no descendants.

It took me another decade to pick up the trail of George’s only son, George Rubin Paine, after he vanished from New Bedford in the 1920s. The internet opened portals to new descendants. I learned that George Rubin Paine died in Los Angeles on 20 November 1955, likely with no knowledge of his father’s Civil War exploits.

It took me another decade to pick up the trail of George’s only son, George Rubin Paine, after he vanished from New Bedford in the 1920s. The internet opened portals to new descendants. I learned that George Rubin Paine died in Los Angeles on 20 November 1955, likely with no knowledge of his father’s Civil War exploits.

Memorial Day beckons us to remembrance. Undoubtedly, George Albion Paine struggled with demons he could not overcome. It saddens me that a Civil War veteran’s grave remains unmarked—a oversight I hope one day to rectify.

Notes

1 George A. Paine, son of Reuben W. and Lovicy (Hall) Paine, is the elder brother of my great-great grandmother, Mary (Paine) (Delano) Sylvia.

2 Michael F. Dwyer, “Some Civil War Soldiers from Block Island,” Rhode Island Roots 38(2012) 29–32.

3 Burial site 25-27, Dahlia Lane, Oak Grove Cemetery, Fall River, Mass. Not listed in findagrave.com.

4 George A. Paine, alias George Payne, Amelia Payne, Pension XC 2684400, present whereabouts of the file unknown.

Share this:

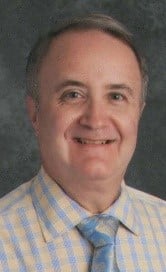

About Michael Dwyer

Michael F. Dwyer first joined NEHGS on a student membership. A Fellow of the American Society of Genealogists, he writes a bimonthly column on Lost Names in Vermont—French Canadian names that have been changed. His articles have been published in the Register, American Ancestors, The American Genealogist, The Maine Genealogist, and Rhode Island Roots, among others. The Vermont Department of Education's 2004 Teacher of the Year, Michael retired in June 2018 after 35 years of teaching subjects he loves—English and history.View all posts by Michael Dwyer →