A few months ago, I chaperoned my daughter’s school field trip to the Paul Revere House in Boston’s North End. I had previously visited this house several times over the course of five childhood summers, when our grandmother would visit New England and bring one of our cousins with her, each of whom would be shown the sights in turn. When Alice mentioned the field trip, I was eager to volunteer, as it had now been thirty years since I was last inside this historic home.

Since I was last there, the Paul Revere Memorial Association has turned a neighboring building into an education and visitor center. Our tour was interactive: the guides assigned each student a different historic role as the tour progressed. Several played members of the Revere family, and Alice was given the part of Paul Revere’s second wife, Rachel. Between his two marriages, Paul Revere had sixteen children, eleven of whom survived childhood.1

After touring the house, we walked over to the famed Old North Church, where we were told Revere had instructed the church’s sexton Robert Newman to light two lanterns to signal that the British troops (or “regulars” as they were called then) were traveling by water. The tour was finished at the nearby Paul Revere Mall, with Alice’s teacher and I being given the final rolls of Samuel Adams and John Hancock, as the guide told how Paul Revere arrived in Lexington as the battle on the green unfolded on 19 April 1775, starting the American Revolution.

Needless to say, whenever I think of the Old North Church of Boston, I think of the church from Paul Revere’s midnight ride, and the building that still stands. However, while working on a Newbury Street Press project, I uncovered documentation which has brought that mental image into question.

I came across my discovery while writing a genealogical summary of Reverend Samuel Checkley, Jr. (1722-1768), who was also the brother-in-law of the previously mentioned patriot Samuel Adams. Rev. Checkley graduated from Harvard College in 1743, and his biography in our database Colonial Collegians referred to him as the Minister of the Old North Church of Boston, with subsequent footnotes referring to the church as the Second [Congregational] Church of Boston. An 1858 history of the congregation is titled “ A History of the Second Church, or Old North, in Boston ”—by the time of that publication, the Second Church had moved out of the North End and had merged with Church of Our Savior on Bedford Street near Boston’s downtown. The Old North Church I visited, officially Christ Church in the City of Boston , was an Anglican (now Episcopal) Church, constructed in 1723 as the second Anglican church in Boston after King’s Chapel. Were there two buildings known as the Old North Church of Boston?

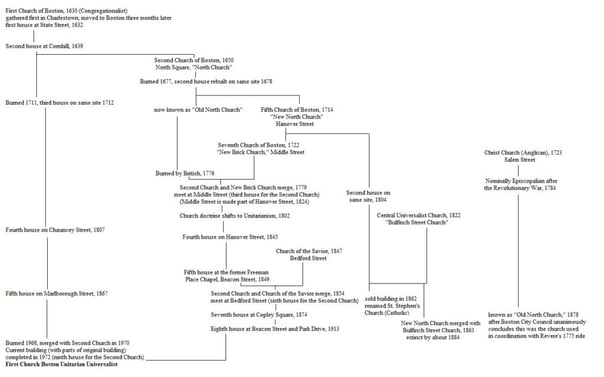

It turns out that there were—sort of. I thought it was time to do another genealogy of churches for original Boston, with a differentiation between Congregational and Anglican faiths. While I intended to make such a chart below, it turns out that there were ELEVEN numbered churches in Boston founded between 1630 and 1748—so the chart only shows creations and mergers in relation to the Second Church and Christ Church.

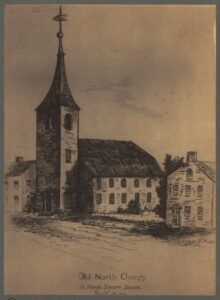

The Second Church was established in 1649 in North Square, with a new building replacing the old in 1677. In 1714, some members split off from the Second Church and formed the Fifth Church of Boston, or the “New North Church.” Five years later, some members of this last church split off and established the Seventh Church of Boston, called the “New Brick Church,” in 1719. As such, the Second Church was called the “Old North Church” to distinguish itself from the New North (the site of the New North Church, replaced with a new structure in 1804, became a Catholic place of worship in 1862 and was renamed St. Stephen’s Church after the influx of Irish Catholics to the North End).

In 1776, with the British troops occupying Boston during the Revolutionary War, the Second Church meeting house was torn down by British troops and ostensibly used for firewood (more on that later). The Second Church then accepted an invitation from the New Brick Church to hold combined services, and in 1779 the two congregational churches merged with the New Brick Church’s meeting house on Hanover Street (built in 1719), becoming the Second Church’s third structure. That church was incorporated as the “Old North, the Second Church in Boston.”2 So, the building that was originally known as the “Old North Church” was built in 1677, and was known by that moniker from 1714 until its end in 1776. Paul Revere, in his own narrative, said that the lanterns were displayed from the “north church steeple.” Was the Anglican Christ Church ever known as the North or Old North Church, and from which church were lanterns sent as a signal?

This “lanterns controversy” is not new. As the Second Church’s Old North building was destroyed in 1776 and subsequently moved out of Boston’s North End by the time of the centennial, the Boston City Council set up an “impartial commission” to determine which church was the one from Revere’s ride. The commission concluded that it was Christ Church, and in 1878 a tablet marked the younger structure (the only one of the two remaining) as the “Old North Church of Paul Revere fame.”

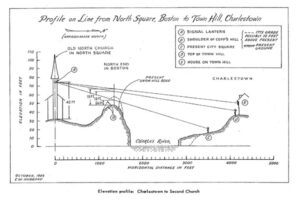

One of the commission’s main arguments was that the steeple of the Second Church was too low to be seen from Charlestown. However, a 1959 work by John Nicholls Booth details a convincing argument in favor of the Second Church. Besides the fact that the Second Church was known as both the North Church and Old North Church in 1775, his illustration to the right shows that the elevation of Boston in 1775 would have allowed for the Second Church’s steeple to be seen from Charlestown. Additionally, the Christ Church was a Tory stronghold, while the Second Church, which was just diagonally across from Revere’s home, was more sympathetic to the patriot cause and would have made a less conspicuous choice. Booth argues that the British burning of the Second Church (the only church they burned during their occupation of Boston) may have occurred because of the role this church played leading up to the Battles of Lexington and Concord.

One of the commission’s main arguments was that the steeple of the Second Church was too low to be seen from Charlestown. However, a 1959 work by John Nicholls Booth details a convincing argument in favor of the Second Church. Besides the fact that the Second Church was known as both the North Church and Old North Church in 1775, his illustration to the right shows that the elevation of Boston in 1775 would have allowed for the Second Church’s steeple to be seen from Charlestown. Additionally, the Christ Church was a Tory stronghold, while the Second Church, which was just diagonally across from Revere’s home, was more sympathetic to the patriot cause and would have made a less conspicuous choice. Booth argues that the British burning of the Second Church (the only church they burned during their occupation of Boston) may have occurred because of the role this church played leading up to the Battles of Lexington and Concord.

It is assumed that Robert Newman was the man instructed to light the lanterns because he was the sexton at Christ Church—Revere never identified the lantern-lighter by name. If the lanterns were lit from the Second Church, then we really have no idea who lit them! Christ Church became known as the “Old North Church” one hundred years after Revere’s ride, on the theory that it was the church made famous in Longfellow’s poem. By then, the Second Church had moved again to Boston’s Copley Square for its seventh structure. It moved once more in 1914, then merged with the First Church of Boston in 1970.3

Which “Old North Church” do you think was the one in Revere’s ride?

Notes

1 Our journal, the Register, published a detailed account of Revere’s ancestry, Andre J. and Pamela Labatut, “Paul Revere’s Paternal Ancestry: The Rivoires: A Huguenot Family of Some Account,” Register, 150 (1996):277-298, along with our manuscript, Herbert Eugene Revere, “A Record of Ancestors and Descendants of Paul Revere.”

2 Paul Revere was a member of the New Brick Church, and thus a member of the Second Church, or Old North Church, after the congregations merged in 1779.

3 The records of the Second Church of Boston from 1650-1970 are available at the Massachusetts Historical Society. For a guide to all Boston churches through 1846, go here.

Share this:

About Christopher C. Child

Chris Child has worked for various departments at NEHGS since 1997 and became a full-time employee in July 2003. He has been a member of NEHGS since the age of eleven. He has written several articles in American Ancestors, The New England Historical and Genealogical Register, and The Mayflower Descendant. He is the co-editor of The Ancestry of Catherine Middleton (NEHGS, 2011), co-author of The Descendants of Judge John Lowell of Newburyport, Massachusetts (Newbury Street Press, 2011) and Ancestors and Descendants of George Rufus and Alice Nelson Pratt (Newbury Street Press, 2013), and author of The Nelson Family of Rowley, Massachusetts (Newbury Street Press, 2014). Chris holds a B.A. in history from Drew University in Madison, New Jersey.View all posts by Christopher C. Child →