On 11 October 1776, 23-year-old Jemima Wilkinson lay close to death in her bed in Cumberland, Providence, Rhode Island, suffering from a fever, possibly typhus. Much to her family’s relief, instead of dying, she awoke and rose from her bed, alive but forever changed. She announced to those around her that she was no longer Jemima Wilkinson, who had died. Her soul had gone to heaven, and in its place, God had sent down a divine spirit charged with preparing his flock for the coming millennium. This holy messenger, neither man nor a woman, was to be known as the “Public Universal Friend.”

On 11 October 1776, 23-year-old Jemima Wilkinson lay close to death in her bed in Cumberland, Providence, Rhode Island, suffering from a fever, possibly typhus. Much to her family’s relief, instead of dying, she awoke and rose from her bed, alive but forever changed. She announced to those around her that she was no longer Jemima Wilkinson, who had died. Her soul had gone to heaven, and in its place, God had sent down a divine spirit charged with preparing his flock for the coming millennium. This holy messenger, neither man nor a woman, was to be known as the “Public Universal Friend.”

The Public Universal Friend lived during a time of widespread religious fervor known as the Great Awakening, which began in colonial America in the early 18th century and continued in successive waves up to the late 20th century. In reaction to the ideas of the Enlightenment and Calvinist theology, the evangelical movement of the 18th century emphasized free will, the possibility of universal salvation, and a personal relationship with God.

The Friend operated within the tradition of the Quaker public Friends, itinerant preachers who were allowed to travel between meetings and communities to preach. However, the Quaker Society of Friends disowned the entire Wilkinson family in response to the Friend’s religious claims. Adherents of the resulting new sect called themselves the Society of Universal Friends, and cut ties with the main body of the Quakers in order to follow the person they often called the “Comforter.”

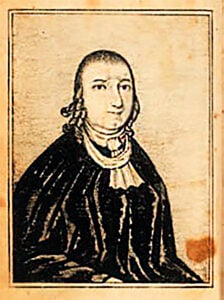

The Public Universal Friend traveled across Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and eastern Pennsylvania, preaching to large crowds. The meetings attracted the attention of local newspapers, which tended to focus on the Friend’s ambiguous gender rather than the content of the sermons, commenting on the preacher’s masculine clothing and hair.

The Universal Friends rejected predestination, encouraged abstinence, and called for the abolition of slavery. In many ways, their theology was very similar to that of mainstream Quakers. However, the perceived transgressive nature of the Friend’s ministry began to attract negative attacks from without and sowed dissension within the group. The fact that women held influential positions in the Society of Universal Friends, and that outsiders often saw male Universal Friends as subservient to their female counterparts, rankled some outside the group. Reports that Wilkinson claimed to be Jesus Christ, along with lurid rumors of attempted murder in the community, began to turn public opinion against them.

In the late 1780s, the Friend and their followers decided to create a place for themselves in the wilderness in upstate New York. They gathered the funds to purchase land in the newly opened Phelps and Gorham Purchase in the Genesee River area. The two towns they built came to be called The Gore and Jerusalem.

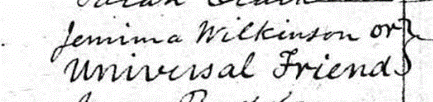

In the 1810 U.S. Federal Census, the Friend appears as “Jemima Wilkinson or Universal Friend” in Jerusalem, Ontario, New York.

Four men and seven women were in the household, four over the age of twenty-four and seven over the age of forty-five. These were the preacher’s closest associates.

Disputes over land, and problems with disillusioned (mostly male) members of the Society, plagued the later years of the Friend’s ministry. Their failing health emboldened their enemies, who decided to pursue litigation over one of these land disputes. In the end, the court found that no indictable offense had occurred, and invited the preacher to give a sermon in the court room.

The Public Universal Friend died on 1 July 1819 in Jerusalem. Their body was placed in a stone vault in the cellar of their house. Years later, it was removed and buried in an unmarked grave. The Society of Universal Friends carried on for a short while without the Comforter, but they were hampered by continuing disputes over land and an inability to attract new members without their charismatic leader. By the 1860s, the sect ceased to exist.