It’s really hard for me to go on vacation without being tempted to do genealogy. I don’t mean my own family—that’s its own problem—I mean researching the history of the place I’m visiting, or the family history of the people who made it a vacation destination.

Case in point: I recently visited the Greenbrier Hotel in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia with my family. Super fancy, very historic. The decoration style isn’t what you’d call modern—the bold colors, wallpaper patterns, bright carpeting, and ornate chandeliers could only work in that space. The sprawling campus is home to a hotel, three golf courses, a spa, horseback riding trails, a casino, and—most compelling of all—a former secret government bunker.1

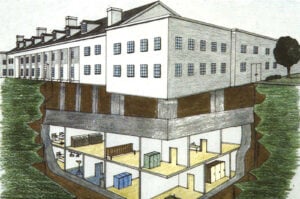

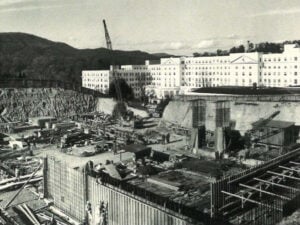

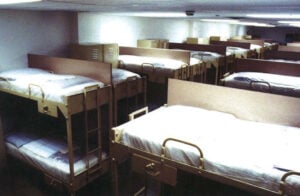

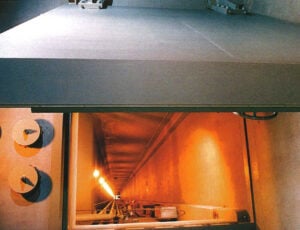

Obviously, I went on a tour of the bunker. The guide was fantastic—she really knew her stuff. The bunker was built between 1958 and 1961 and served as the top-secret emergency relocation facility for the U.S. Senate and the House of Representatives from 1961 to 1992. As we walked through the bunker, buried 720 feet into the hillside under the Greenbrier Hotel, we saw the rooms where members of Congress would have eaten, slept, and continued the functions of government in the event of a national emergency, safely hidden from adversaries. The bunker included a power plant, a communications briefing room, security systems, an intensive care unit, a fully stocked pharmacy, dormitories, a cafeteria and kitchen, and meeting rooms. They kept enough supplies to last 40 days.2 Our tour guide didn’t have an answer as to what they would have done after 40 days were up…

Obviously, I went on a tour of the bunker. The guide was fantastic—she really knew her stuff. The bunker was built between 1958 and 1961 and served as the top-secret emergency relocation facility for the U.S. Senate and the House of Representatives from 1961 to 1992. As we walked through the bunker, buried 720 feet into the hillside under the Greenbrier Hotel, we saw the rooms where members of Congress would have eaten, slept, and continued the functions of government in the event of a national emergency, safely hidden from adversaries. The bunker included a power plant, a communications briefing room, security systems, an intensive care unit, a fully stocked pharmacy, dormitories, a cafeteria and kitchen, and meeting rooms. They kept enough supplies to last 40 days.2 Our tour guide didn’t have an answer as to what they would have done after 40 days were up…

Regardless, the whole operation was incredibly organized, meticulously planned, and most importantly, one of the best kept secrets in the country—it was successfully hidden for almost thirty years!

I find myself most intrigued by the people who kept this place a secret. A facility of that size, requiring constant maintenance and turnover of supplies (they kept fresh fruit and veggies in addition to MREs), would need a large staff—and an unassuming staff, at that.

I find myself most intrigued by the people who kept this place a secret. A facility of that size, requiring constant maintenance and turnover of supplies (they kept fresh fruit and veggies in addition to MREs), would need a large staff—and an unassuming staff, at that.

Our tour guide spoke about the top-secret government staffers who worked at the Greenbrier Hotel, and their cover stories. Apparently, they posed as TV repairmen working for a shell corporation called Forsythe Associates. Their office, located just inside the entrance to the bunker, appeared unassuming—nothing more than a place to store broken equipment, cables, cords, and tools to repair the 1,000 television sets located throughout the hotel.3 A securely-locked closet at the back of the office led into the secret 112,544 square foot facility.4

One of the displays we saw included a few examples of the staffer IDs from Forsythe Associates. One badge, belonging to a man by the name of Jasper Abner Boone, stuck in my mind. So, as you can guess, I had to look him up. (Unfortunately, we weren’t allowed to take photos on the tour—the photos you see in this post were provided to tour participants.)

One of the displays we saw included a few examples of the staffer IDs from Forsythe Associates. One badge, belonging to a man by the name of Jasper Abner Boone, stuck in my mind. So, as you can guess, I had to look him up. (Unfortunately, we weren’t allowed to take photos on the tour—the photos you see in this post were provided to tour participants.)

Jasper Abner Boone was born on 18 April 1919 in Covington, Virginia to Henry Roy Boone and Mary Christine Miller.5 He lived in Organ Cave, Greenbrier County, West Virginia and enlisted with Company F of the West Virginia 150th Infantry at Ronceverte on 16 May 1939.6 He continued to serve with the U.S. Army from 10 August 1943 to 27 May 1949, and again from 1 August 1950 to 6 September 1951.7 Most censuses fail to identify his occupation, but interestingly, the household enumeration in 1950 shows that his brother, Cecil Alexander Boone, and his brother-in-law, William H. Holyman, both worked as carpenters at a hotel.8 When I pressed further, I found that Cecil and his wife, Imogene Louise Reynolds both worked for the Greenbrier Hotel in August of 1961—the same year the bunker became fully functional.9

Did all of these family members work to maintain the bunker? Probably not. I doubt that working as a TV repairman would have been a suitably low-profile alter ego for a woman in 1961. But it’s possible that Abner worked with his brother, Cecil, to protect the secret of the bunker. We have no way of knowing, given the lack of documentation and confidential nature of the bunker, but it’s fun to think about— imagine keeping such a huge secret from your family for 30 years!

Notes

1 Project Greek Island: The Bunker , Brochure, The Greenbrier.

2 Project Greek Island: The Bunker , Brochure, The Greenbrier.

3 Gup, Ted. The Ultimate Congressional Hideaway, The Washington Post, Sunday, May 31, 1992, Page W11.

4 Project Greek Island: The Bunker , Brochure, The Greenbrier.

5 Jasper Abner Boone birth record, Virginia, U.S., Birth Records, 1912-2015, Delayed Birth Records, 1721-1920 , Ancestry.com.

6 Jasper Abner Boone enlistment record, Office of the Adjutant General, West Virginia, 1939; Jasper Abner Boone service record, Office of the Adjutant General, West Virginia, 1940.

7 Jasper A. Boone, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs BIRLS Death File, 1850-2010 , Ancestry.com, pg. 1.

8 Household of Henry R. Boone, 1950 Federal Census, Irish Corner, Greenbrier, West Virginia, www.ancestry.com, sheet 38.

9 Boone-Reynolds marriage, Covington Virginian, Covington, Virginia · Wednesday, August 30, 1961, pg. 5.

Share this:

About Lindsay Fulton

Lindsay Fulton joined the Society in 2012, first a member of the Research Services team, and then a Genealogist in the Library. She has been the Director of Research Services since 2016. In addition to helping constituents with their research, Lindsay has also authored a Portable Genealogists on the topics of Applying to Lineage Societies, the United States Federal Census, 1790-1840 and the United States Federal Census, 1850-1940. She is a frequent contributor to the NEHGS blog, Vita-Brevis, and has appeared as a guest on the Extreme Genes radio program. Before, NEHGS, Lindsay worked at the National Archives and Records Administration in Waltham, Massachusetts, where she designed and implemented an original curriculum program exploring the Chinese Exclusion Era for elementary school students. She holds a B.A. from Merrimack College and M.A. from the University of Massachusetts-Boston.View all posts by Lindsay Fulton →