Before joining NEHGS as a researcher, I worked with the National Parks of Boston researching patriots of color from Massachusetts who served during the Revolutionary War. While doing this research, I spent time looking through pension records to gain an understanding of these soldiers’ experiences during and after the war. I did not initially know what to expect from these records, but I quickly realized that they can be a treasure trove of information.

Before joining NEHGS as a researcher, I worked with the National Parks of Boston researching patriots of color from Massachusetts who served during the Revolutionary War. While doing this research, I spent time looking through pension records to gain an understanding of these soldiers’ experiences during and after the war. I did not initially know what to expect from these records, but I quickly realized that they can be a treasure trove of information.

Although Congress provided pensions for certain groups, such as those who had been disabled while serving, it wasn’t until 1818 that all men who served in the army or navy became eligible to receive a lifetime pension. To qualify, they had to prove that they needed financial assistance due to “reduced circumstances in life.”[1] In order to do this, they had to list all their property and wages in their applications. Some considered the process of describing their poverty humiliating. Still, these lists give us a glimpse of what life was like for many Revolutionary War veterans after the war.

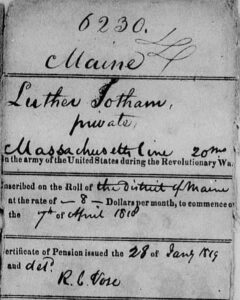

One example is of Massachusetts veteran Luther Jotham, who later relocated to Maine. Though he worked as a yeoman—a man who farmed his own land—for several decades after he served, his ability to support himself and his family eventually dwindled over time. At 69 years of age, Jotham applied for a pension and listed his few belongings, which included a house, several tools and household items, and a few farm animals. When describing his yearly wages, he stated: “My income does not exceed five dollars a year. I am by occupation a labouring man but from age and infirmity unable to do but little.”[2] Jotham’s application was approved, and he received an annual pension until he died. (Congress rescinded the financial need requirement in 1832.)

Pension records can also tell us about a former soldier’s family and acquaintances.

Pension records can also tell us about a former soldier’s family and acquaintances. The applications generally mention wives and children, but will often include testimonies from friends or fellow veterans who vouched for the applicant’s service. For instance, the application of Private David Woolly of Boston included a statement from Revolutionary War veteran Primus Hall, who testified that Woolly “served with [him] one year in 1776, and six weeks in 1777 under Capt. Butler, Lieutenant Silas Walker, and Ensign Wheeler, in Colonel John Nixon’s Regiment. While we were in said service we went to New York and New Jersey and were at the Battle of Princeton...”[3] Testimonies such as this allow us to pinpoint those with whom these veterans were acquainted and provide a better understanding of their communities.

It is important to note that pension records vary in length. While some are up to 100 pages long, others are only a few pages and contain very basic information. Still, those on the longer side can help provide insight into the lives of America’s first veterans. What interesting information have you found while looking through pension records?

Notes

[1] Michael Barbieri, “Good and Sufficient Testimony: The Development of the Revolutionary War Pension Plan,” Journal of the American Revolution (26 August 2021), https://allthingsliberty.com/2021/08/good-and-sufficient-testimony-the-development-of-the-revolutionary-war-pension-plan/.

[2] Luther Jotham, Pension No. W. 9911, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. NARA M804, page 18. Accessed via Fold3.com.

[3] David Woolly, Pension No. W. 15735, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. NARA M804, page 12. Accessed via Fold3.com.