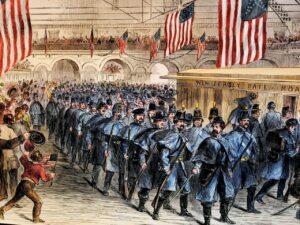

"The Sixth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers Leaving Jersey City R.R. Depot, To Defend The Capitol, at Washington, D.C., April 18th, 1861," published in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper in 1861.

"The Sixth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers Leaving Jersey City R.R. Depot, To Defend The Capitol, at Washington, D.C., April 18th, 1861," published in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper in 1861.

When researching the American Civil War, battles and generals are often discussed in depth and the individual everyday stories and struggles of the common soldiers can be neglected in the larger story of the war. A story of particular interest to me is the story of Charles Taylor, a 25-year-old private from Massachusetts, who is often cited as the first soldier killed in the Civil War.

At approximately 4:30 in the morning of 12 April 1861, Confederate soldiers opened fire on Fort Sumter, in Charleston, South Carolina. Although neither side sustained casualties during the battle, this event is widely regarded as the start of the American Civil War. On 15 April, President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers from across the country to enlist to suppress the rebellion. One of the many units that quickly assembled that week was the 6th Massachusetts State Militia.

The 6th Massachusetts primarily recruited in Lowell, Massachusetts. The regiment had been outfitted and organized in Lowell before making the march to Boston. The men quartered for the night in Boylston Hall in downtown Boston. Two hours before the regiment was to travel south and into the war, a stranger entered Boylston Hall and requested to join the regiment. He told the officers that his name was Charles Taylor and that he was a painter by occupation.[1] He was described as roughly twenty-five years old with a light complexion and blue eyes.

Since the regiment had already received its uniforms and equipment in Lowell, Charles left Massachusetts in civilian clothing. The regiment was loaded into train cars and began its journey south to Washington, D.C., to help protect the Capital.

On 19 April 1861, the regiment arrived at the train depot in Baltimore, Maryland. The troops began their march through the city of Baltimore headed to the next train depot, to switch trains. While Maryland did not secede during the Civil War, at the time the regiment was marching down Pratt Street, the city was aflame with the fire of rebellion. Many Baltimore citizens sided with the Confederacy and were enraged at the sight of fully uniformed troops marching through their streets.

Many Baltimore citizens sided with the Confederacy and were enraged at the sight of fully uniformed troops marching through their streets.

The leader of the regiment, thirty-two-year-old Colonel Edward F. Jones from Pepperell, Massachusetts,[2] had received word that an angry mob was gathering in Baltimore and warned his troops about the threatened unrest. He wrote:

“After leaving Philadelphia, I received information that our passage through the city of Baltimore would be resisted. I caused ammunition to be distributed, and arms loaded; and went personally through the cars and issued the following order: The Regiment will march through Baltimore in column of sections, arms at will. You will undoubtedly be insulted, abused, and perhaps assaulted, to which you must pay no attention whatever; but march with your faces square to the front, and pay no attention to the mob, even if they throw stones, bricks or other missiles; but if you are fired upon, and any one of you is hit, your officers will order you to fire.”[3]

As the men disembarked the train and began to march down Pratt Street, they were attacked by a mob hurling bricks and rocks. In the chaos, shots rang out and the crowd and the soldiers began to clash. Three Union soldiers were killed in the fight, and another died soon after from injuries. These men would become the first casualties of the American Civil War. It is unclear which of the four was the first to die in the ensuing fight, but later newspaper sources claimed that Charles Taylor was the first death of the American Civil War.

Since Charles was not in a soldier’s uniform and was a stranger to the rest of the unit at the time of the riot, he was not originally counted as an official death.[4] It wasn’t until weeks later that Captain Hart of the 6th Massachusetts received a package containing Charles Taylor’s overcoat. It had been mailed by an anonymous man who had witnessed the mob beating Charles with clubs and rocks who wanted to return his coat to the family. Upon receiving the coat, the soldiers of the 6th Massachusetts Militia realized for the first time that Charles Taylor was missing and had been killed during the riot.[5] A search was conducted to find his family and notify them of his death. However, they had no luck.

...Charles Taylor, the first soldier to be killed in the American Civil War, was overlooked by the news of the time.

And so, Charles Taylor, the first soldier to be killed in the American Civil War, was overlooked by the news of the time. The remains of the other two soldiers killed in the fight were given public funerals and commemorated with a granite monument in downtown Lowell bearing their names: Addison Whitney and Luther Ladd. The commemoration ceremony was attended by more than 4,000 mourners.[6]

As time passed, the Pratt Street riots slowly became a footnote in the history of the war. However, one man never forgot that day and made it his mission to bring Charles Taylor’s remains home and give him a decent burial just as the Whitney and Ladd had. Edward Jones, the commander of the 6th Massachusetts on the day of the riot, had been searching for years to find the body of Charles Taylor. He made multiple trips to visit Baltimore from Binghamton, New York to track down leads to the whereabouts of his burial, all of which were unsuccessful. In 1909 Jones finally received a tip. A man named Frank West had seen the mob beating a man in civilian clothing and tried to help the man. West had to flee for his own safety.[7] He remembered seeing the mob throwing the body of this man into the sewers.

Using this information, Edward Jones traveled back to Baltimore and took out an ad in the newspaper chronicling his meeting with a former policeman who was working the day of the riot. This officer claimed to have heard that, after the riot, the remains of an unknown man were “found in the mouth of the sewer on Pratt Street and Bowleys Warf. What disposition was made of the body he does not know.” Jones, however, did not stop there. He next met with a well-known citizen of Baltimore who stated that “one of the bodies found in civilian garb after the passage of the troops could not be identified and was, he thinks, buried in Baltimore Cemetery.” While Jones was investigating, he learned of a man named Leven Gorsuch who owned a small plot in the cemetery. While Gorsuch had died years before Jones started his investigation, there were “several occasions (Gorsuch) is said to have stated that this grave contains the remains of one of the Massachusetts victims of the riot.” Jones ended the article with a plea for any more information people might have regarding Taylor on that day.

A year later, Colonel Jones returned to Baltimore from New York. Now in his eighties and completely blind, he returned with his daughters. He had successfully received permission to excavate the gravesite in Leven Gorsuch’s family plot. The Baltimore American reported:[8]

“It was said, that (Taylor) had been buried in the lot of Mr. Leven W. Gorsuch. Yesterday, however, the foundations of this theory were shattered, for after excavating the spot which was supposed to contain the remains, no trace of them were found. Not a single bit of rotten wood, brass accouterments, or leather was disclosed to the view of those who peered anxiously into the excavation, and it was the opinion of all those present that ground at that spot had never before been unearthed. Finally, after the grave-diggers had been at work for about two hours and a half and had made a hole seven feet deep, General Jones began to realize he that his efforts to secure possession of the remains were again baffled, and he notified the grave-diggers that they were at liberty to discontinue their work… He then left the cemetery on the arms of his two daughters, saying that he was going directly to the station to take the train for Philadelphia, where he is to rest before going on to his home.”

Edward Jones died at his home in Binghamton, New York in 1913 at the age of eighty-five. However, before his passing, he made sure that a bronze placard was affixed onto the Ladd-Whitney Monument in Lowell, Massachusetts to commemorate the life of Charles Taylor, securing his place alongside his fellow soldiers as the first deaths of the American Civil War.[9] On Memorial Day we look back and remember the lives of soldiers like Charles Taylor who gave the ultimate sacrifice for their country.

Notes

[1] John Wesley Hanson, Historical Sketch of the Old Sixth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers, During Its Three Campaigns in 1861, 1862, 1863, and 1864 (Boston: Lee & Shepard, 1866), 47.

[2] Massachusetts Soldiers, Sailors and Marines in the Civil War (Boston: Massachusetts Adjutant General's Office, 1931), 1: 372.

[3] Hanson, Historical Sketch of the Old Sixth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers, 37.

[4] Baltimore American, 22 June 1910, 18.

[5] Hanson, Historical Sketch of the Old Sixth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers, 48.

[6] Worcester Spy, 8 May 1861, 2.

[7] Baltimore Sun, 1 August 1909, 23.

[8] Baltimore American, 22 June 1910, 18.

[9] https://macivilwarmonuments.com/tag/ladd-and-whitney-monument/.

Share this:

About Jonathan Hill

Jonathan Hill is a full-time researcher at NEHGS; he earned his BFA from Lesley University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Jonathan previously served as a board member on the Friends of the Town of Bedford Cemeteries. He has contributed to the Green-Wood Cemetery’s Civil War Project and to many other historical volunteer projects across the country.View all posts by Jonathan Hill →