Wouldn’t you know it. No sooner had I submitted a blog post about the MACRIS database to Vita Brevis then I discovered the entire website had been redesigned. So, it was back to the drawing board to learn how to re-navigate it. It was worth it, however, to be able to rewrite this post and share this database.

For those who might be undertaking research about historic properties and landmarks in Massachusetts, the Massachusetts Cultural Resource Information System (MACRIS) is well worth a visit, filled as it is with fascinating information documented over several decades – generally from the 1960s thru the 1990s – by local historical commissions, some of whose members were more intrepid than others, and collected under one umbrella by the Massachusetts Historical Commission (MHC). The original paper records, each with a cover page and a standardized template, have been scanned.

Established by the legislature in 1963, the MHC, consisting of seventeen members from various disciplines (including the New England Historic Genealogical Society), is tasked with identifying, evaluating, and protecting the state’s historical and archeological assets. In my initial post, I had written that the “old” MACRIS database seemed a little less than user-friendly to the newcomer, but that in no time you’d find yourself smoothly navigating the towns and categories.

I have to admit that the new design – though I am an old dog who doesn’t like new tricks – is actually more user-friendly than the old version. You will find yourself marveling not only at the wealth of cultural assets here in the Commonwealth but impressed with the diligence by so many individuals over the years who researched and recorded those assets for posterity. While other states appear to have cultural heritage databases, I have not investigated them thoroughly enough to assess how comparable they may be to our MACRIS. Perhaps Vita Brevis readers can and will share their experiences.

You will find yourself marveling not only at the wealth of cultural assets here in the Commonwealth but impressed with the diligence by so many individuals over the years who researched and recorded those assets for posterity.

To begin using the database, get yourself to the MACRIS home page at the Massachusetts Historical Commission, a department of the Secretary of State. Once you acknowledge and accept the terms and disclaimer at the bottom of the page, you’ll be taken to the search page. On the left, under Search Filters, select the city or town that is of interest to you from the list of alphabetized options and ALL the cultural and historic resources for that city or town will be displayed. The Search Filters then allow the user to refine the search with numerous subcategories, including Address, Historic Name, or Resource Type.

Resource Type is a holdover from the earlier version, and it is the filter that I find myself using most frequently to get a narrower view of the town’s inventory but a broader selection than what, for instance, an address might offer. Resource Type is especially helpful if the researcher is not quite certain what to look for and would like a selection of “possibilities.” Resource Type offers five subcategories: Area, Building, Burial Ground, Object, or Structure. This is where it can get a little tricky as you try to categorize what it is you are looking for. Is it a building or a structure … a structure or an object?

“Area” tends to include historic districts, farms, and neighborhoods. Most dwellings with a street address will be found in the “Building” category. “Burial Ground” includes town and private cemeteries and may include family cemeteries. “Object” includes monuments, statues, and markers. “Structure” seems to be the most eclectic category and may include piers, bandstands, ancient trees, and herring runs. The more one uses the database, the more one gets a feel for where one might find an asset.

“Area” tends to include historic districts, farms, and neighborhoods. Most dwellings with a street address will be found in the “Building” category. “Burial Ground” includes town and private cemeteries and may include family cemeteries. “Object” includes monuments, statues, and markers. “Structure” seems to be the most eclectic category and may include piers, bandstands, ancient trees, and herring runs. The more one uses the database, the more one gets a feel for where one might find an asset.

After selecting the Resource Type, your town list will be refined to only display the inventory for that Type. With any luck you’ll see what you hoped to find. Even by browsing the unrefined results, you may find something unexpected that helps with your research. If you come up empty-handed, keep looking (though not every asset in every town has been surveyed): it may be listed under a different heading. For instance, Plymouth’s Old Burial Hill survey can be found under Burial Ground, but many individual markers can be found under Object.

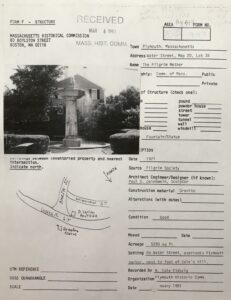

Each result may include the property name; street address, if applicable; a construction date estimate; a thumbnail photograph; and designation of SR (State Register) or NR (National Register), if applicable. If it’s your lucky day, you’ll see a blue box marked INV confirming that a record awaits. Clicking the box will download the scanned file.

If it’s your lucky day, you’ll see a blue box marked INV confirming that a record awaits.

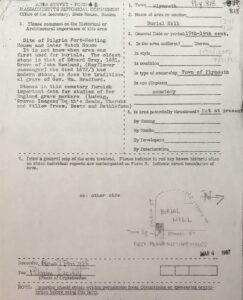

Some files are lengthy, others brief; some richly descriptive, other perfunctory. Some inventories contain photographs and hand drawn maps. As I explored the files, I couldn’t help but think that like the handwriting by census enumerators, the handwriting and random notations in these files can occasionally be challenging, but better something than nothing. We are fortunate to have this information at our fingertips.

The best records are those that have “stories” mixing historical information (and bibliographic and reference information) with local lore, the kind of folksy anecdotal information that is rarely found in formal town histories. Given the lengths of time that have transpired since most of the surveys were completed and the fury with which buildings have been altered, one should expect that some of the descriptive architectural information may no longer be current.

I use the database regularly and find it particularly useful for researching the ownership and conveyance of old houses. I was recently asked to do a bit of research for the property that now houses the Truro Vineyards on Cape Cod. It was one of the more complete records I’ve perused, rich with detail, neatly typewritten and with a clearly drawn map. A record such as the one for Truro Vineyards may offer hints for additional research, names that may be further explored genealogically, as well as references that may assist in ancillary research. Happy hunting!

Share this:

About Amy Whorf McGuiggan

Amy Whorf McGuiggan recently published Finding Emma: My Search For the Family My Grandfather Never Knew; she is also the author of My Provincetown: Memories of a Cape Cod Childhood; Christmas in New England; and Take Me Out to the Ball Game: The Story of the Sensational Baseball Song. Past projects have included curating, researching, and writing the exhibition Forgotten Port: Provincetown’s Whaling Heritage (for the Pilgrim Monument and Provincetown Museum) and Albert Edel: Moments in Time, Pictures of Place (for the Provincetown Art Association and Museum).View all posts by Amy Whorf McGuiggan →