During the Revolutionary War, the Continental Navy played an integral role in the colonists’ quest for freedom. The Navy also launched numerous careers, including those of Captains John Paul Jones and John Barry. During the Revolution, many men fought bravely defending the shores of the Colonies and capturing enemy vessels. After the war, the troops and sailors were discharged and the Continental Navy itself was dissolved for lack of financing. After a total of ten years without a navy, in March 1794 Congress passed the Naval Act, which launched the first United States Navy.[1] Over the next two centuries the Navy continued to grow to become the extensive branch of the military we currently know. In the words of John Adams, the ‘Father of the American Navy,’ “A Naval power … is the natural defense of the United States.”[2]

As the Navy continued to grow in influence, the heroes of the seas like Jones and Barry retained their eminence. However, there is one important sailor whose story has been lost to time. Captain Seth Harding was arguably the most prominent sailor to come from Connecticut during the Revolution.

Seth Harding was born on 17 April 1734 at Eastham, Massachusetts. After the death of his wife Abigail Doane, Seth Harding settled at Norwich, Connecticut with his daughter. He was heavily involved in trade with the West Indies and Nova Scotia. Captain Harding even operated his own salmon fishery, which he moved to Liverpool, Nova Scotia to open in 1771. At the start of the Revolution Captain Harding returned to Connecticut to do his part in the coming conflict.[3]

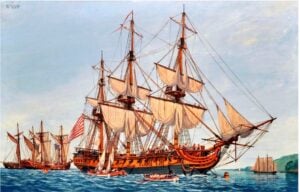

Seth Harding was one of the few sailors who served throughout the entire war. He first captained the Brigantine-of-War Defence, with which he pursued Tories attempting to cross the Long Island Sound with harmful intelligence. Captain Harding later took command of the Connecticut State Man-of-War Oliver Cromwell in April 1777. A year later, Governor Jonathan Trumbull specially approached the Continental Congress Marine Committee to put forth Seth Harding as the new commander of the Continental Frigate Confederacy. After taking command of the vessel, Captain Harding was charged with conveying two dignitaries across the Atlantic. On 17 September 1779, Captain Harding received orders to sail from Philadelphia to France with the new American Minister to Spain, John Jay, and the French Minister Alexandre Gerard de Ayneval. Unfortunately, they were unable to complete the trip following a disastrous storm which led to the Confederacy being dismasted. For the remainder of the war, Captain Harding was captured, held prisoner, and then returned to service aboard Captain John Barry’s Alliance, where he was wounded on 10 March 1783 during the final naval battle of the Revolution.[4]

He wrote a number of letters over a period of ten years to James Madison and Presidents John Adams and Thomas Jefferson about the prize money due to him...

With such an illustrious naval career, it seems impossible that Captain Seth Harding’s name would not be as well-known as Captains Jones and Barry. Unfortunately, after his discharge from the navy, Captain Harding moved to New York where he fell into poverty. He wrote a number of letters over a period of ten years to James Madison and Presidents John Adams and Thomas Jefferson about the prize money due to him, but was ultimately denied.[5] His last days were obscure, and Harding died sometime in 1814 at Schoharie County, New York.

Sadly, the grave of the naval hero seemed to have been lost to history. But in an interesting turn of events, a review of Colonel J. L. Howard’s biography (Seth Harding, Mariner) was published in The Hartford Courant in 1930. The article mentioned that Seth Harding’s grave was located somewhere in Schoharie County, which triggered Colonel E. Vrooman to come forward with information on the lost grave.[6] Through the literary work of Colonel Howard and a little bit of luck, Captain Harding’s legacy is beginning to come to light. It seems only natural that people should know more about one of Connecticut’s most prominent heroes of the Revolution.

Notes

[1] “Launching the New U.S. Navy,” National Archives and Records Administration, www.archives.gov/education/lessons/new-us-navy/act-draft.html, accessed 30 July 2021.

[2] Nathan Miller, The U.S. Navy: A History, 3rd ed. (Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1997), 9.

[3] Louis F. Middlebrook, History of Maritime Connecticut During the American Revolution, 1775-1783, 2 vols. (Salem, Mass.: Essex Institute, 1925), 1: 48-49; William James Morgan, Captains to the Northward: the New England Captains in the Continental Navy (Barre, Mass.: Barre Gazette, 1959), 144.

[4] Middlebrook, History of Maritime Connecticut, 1: 43-44, 48-50, 80-84; Henry Phelps Johnston, Record of Service of Connecticut Men in the I. War of the Revolution, II. War of 1812, III. Mexican War (Hartford: Connecticut Adjutant-General's Office, Connecticut General Assembly, 1889), 593, 596; Thomas S. Collier, The Revolutionary Privateers of Connecticut with An Account of the State Cruisers (New London, Conn., 1892), 60-62.

[5] “To Thomas Jefferson from Seth Harding, 13 January 1806,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/99-01-02-3004; “To James Madison from Seth Harding, [ca. 12 July] 1790,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-13-02-0197.

[6] The Hartford Courant, 17 November 1930, 3 (online database, Newspapers.com), 30 July 2021.

Share this:

.jpg)

About Elizabeth Peay

Elizabeth works as a genealogist for the Publishing team, writing for the Newbury Street Press. Using extensive research and advanced scholarship, she compiles and produces family history projects to meet the highest scholarly standards. One of Elizabeth’s most notable works is the three volume Biographies of Original Members and Qualifying Officers: Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Connecticut. Throughout her work, Elizabeth stays in contact with the Advancement team in order to ensure a strong line of communication with her clients. She also works with the Education department to create and deliver lectures, some of which have focused on colonial New England genealogy and Revolutionary War genealogy. Elizabeth has also contributed to the Vita Brevis blog. Prior to her work with American Ancestors, Elizabeth studied at the University of Connecticut and Smith College, earning a dual BA in History and Classical Studies. She completed an internship for the Tiffany Windows Education Center in Boston and worked for Historic New England at Roseland Cottage. Elizabeth’s areas of expertise include colonial New England, the French and Indian War, the Revolutionary War, Land Bounty records, and Pension records.View all posts by Elizabeth Peay →