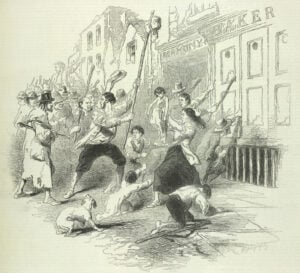

The Irish potato famine is notorious even today because it killed one million people and prompted two million people to emigrate from Ireland. Signs of the famine can still be found in Ireland today, whether in the form of various ruins whose occupants had all perished or in the form of graves marked solely by rocks. Moreover, Irish emigration fluctuated so much that many voyages took place on coffin ships – small ships aptly named for the increased mortality rate onboard. Many immigrants were so desperate to leave their homeland that they booked inexpensive passage on ships that were small, overcrowded, and ravaged by disease and other unfavorable conditions. Based on these facts, arguably, many Americans with Irish ancestry can connect theirs to this event.

My family is one such example. My great-great-grandfather, Patrick Hayes, was born in County Clare in 1847, known as the worst year of the famine. He lived the rest of his life in Springfield, Missouri, and according to his death certificate, from 1924, was born to a John Hayes. However, uncovering his immigration records has become one of my brick walls. While the United States Famine Passenger Index does have a record of a Patrick Hayes arriving in New York in 1849, it is difficult to determine if this is indeed my great-great-grandfather. If it was him, why wasn’t his father on board the Rappahanock with him? The informant for his death certificate was my great-grandmother, Virginia Hayes. What I gathered from this information was that she knew her grandfather personally but had never met her grandmother, hence explaining why her name was not given. Was Mrs. Hayes the one who put her son aboard the ship, and was his father already waiting for him in America?

One of the more frustrating aspects of Irish migration is that, due in large part to the overwhelming number of people who left Ireland during the famine years, records were not kept diligently.

One of the more frustrating aspects of Irish migration is that, due in large part to the overwhelming number of people who left Ireland during the famine years, records were not kept diligently. Ellis Island had not yet been built, and people were not opposed to sneaking aboard or giving their children to somebody who had a ticket (usually due to eviction). Additionally, ships landed in several different ports besides New York, including Boston and Philadelphia. Therefore, not only were immigration records not quite up to par, they tripled due to the sheer number of ports and possible ships. Based on these facts, I was led to believe that my own ancestors arrived in America on one of the notorious coffin ships, and that my great-great-great-grandmother became a statistic, one of the 30% of passengers who never survived the voyage.

Pat Hayes became a police officer in Springfield, so despite his impoverished beginnings, he made a stable life for himself. Like many of the Irish who were fortunate enough to survive the famine, he overcame the tragedy that scarred his native country so severely.

Share this:

About Maureen Carey

A native of San Francisco, Maureen Carey has a B.A. in European History from Regis University and a M.A. in American History from the University of Colorado. She is passionate about genealogy and has enjoyed tracing her own ancestry to colonial America. Her many research interests include America, Ireland, and Italy. In her free time, Maureen loves to read, travel, and spend time with her family, friends, and pets.View all posts by Maureen Carey →