Surnames of formerly enslaved people can add a lot of confusion when trying to piece together families. Many enslaved individuals were denied an official surname prior to emancipation, and the adoption of surnames following freedom did not follow any prescribed method. In some cases, the surname of the former slave owner was either adopted by choice or assigned to them in the first records in which they appear as free individuals. If these surnames were not taken by choice, some people abandoned them as the years passed and took on new names or reclaimed old family names. In some cases, individuals had their own previously-unrecognized surnames that they had passed down for generations finally put on official records once they were free. There is a great article on the complexity of slave surnames here.

There were some other Black families living nearby, also with the Thompson name, but a connection could not be made to Wesley.

Recently, I was looking for more information on Wesley Thompson, who was born about 1835 and who was living in Morgan County, Alabama with his wife, Nellie, and five children in 1880. On the U.S. Federal census that year, Wesley’s birthplace was recorded as Alabama, the same as his father, and his mother’s birthplace was South Carolina. There were some other Black families living nearby, also with the Thompson name, but a connection could not be made to Wesley. One potential scenario was that they may all have had the Thompson surname because they were all enslaved by the same slaveowner.

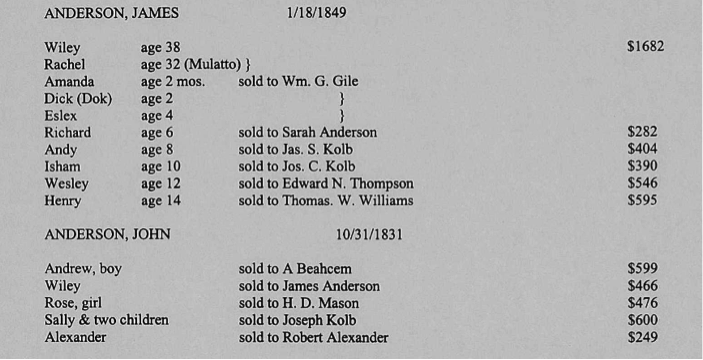

In my search for a slave owner with the name Thompson, I came across a rather hidden collection of abstracted slave information from estate files in Morgan County. The collection was not indexed, but it was in alphabetical order by slaveowner. Instead of jumping right to the name Thompson, I decided a better method might be to browse for any enslaved people named Wesley who were about the right age to be the 1880 Wesley Thompson, since the surnames could be different. As luck would have it, the very first page had an abstract for the estate of James Anderson in 1849, with a Wesley, aged 12, sold to Edward N. Thompson. His birth was close to the Wesley in question, and the Thompson surname of the slaveowner caught my attention.

The abstract records what appears to be a family unit – Wiley and Rachel with eight children ranging in age from two months to fourteen years old. The three youngest children were sold with the parents to Wm. G. Gile, and the other five children were all sold to different individuals. Records like this are a harsh reminder of families being torn apart by slavery. It seemed like this could be a record for our Wesley, and it told the tragic tale of a young boy taken away from his parents and siblings to be enslaved by a new owner. I also noted that the next abstract for the estate of John Anderson in 1831 records the father, Wiley, being sold to James Anderson, so the family had a history with the Andersons.

Seeing this record alone one might wonder why John Wesley’s surname is Thompson if both his parents have the surname Gyle...

A death record for Wesley’s son, Hezekiah Thompson, gave his father’s name as John Wesley Thompson. This was the only record that gave Wesley’s name as John Wesley instead of just Wesley. This information helped in locating Wesley’s death record, which recorded his parents as Wiley Gyle and Rachael Gyle. This is certainly a record for the Wesley in question based on his known address at time of death. Seeing this record alone one might wonder why John Wesley’s surname is Thompson if both his parents have the surname Gyle; taken with the estate record for James Anderson, it becomes clear that the family members were sold to different slave owners and therefore either adopted or were given the surnames of their most recent slaveowners following emancipation. This is a good example of why considering all options and casting wide nets can sometimes lead to success when searching for formerly enslaved ancestors.

It can be so difficult to face the tragic realities of the past, but the records for this family demonstrate the strength and perseverance they had not only to survive, but to fight back and to stay connected as a family. Once the different surnames were noted, it became clear looking at post-emancipation documents that this family remained close. The brothers even served in the Union Army together, fighting against slavery. Many say that we can "give" a voice to those silenced by history, but I argue that our ancestors always had a voice and agency over their own lives, regardless of their status. It is our job as genealogists to hear those stories through the records we find. I believe it is important to think this way when researching enslaved ancestors who may seem to have no control over their lives, yet who, regardless of what was done to them, made a choice to keep going, keep living, and keep loving each other. There is great power in that.

Share this:

About Meaghan E.H. Siekman

Meaghan joined the American Ancestors staff in 2013 as a Researcher before moving to the Publications team in 2018 where she is currently a Senior Genealogist of the Newbury Street Press. As a part of the Publications team, Meaghan researches and writes family histories and other scholarly projects. She also regularly develops and presents lectures as well as other educational material on a variety of research topics. Additionally, Meaghan serves as the American Ancestor's representative to the New England Regional Fellowship Consortium. Meaghan holds a PhD in history from Arizona State University where her focus was public history and American Indigenous history. Prior to joining American Ancestors, she worked as Curator of the Fairbanks House in Dedham, Massachusetts and as an archivist at the Heard Museum Library in Phoenix. Meaghan also worked for the National Park Service and wrote several Cultural Landscape Inventories, most notably for Victoria Mine within the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Her doctoral dissertation, Weaving a New Shared Authority: The Akwesasne Museum and Community Collaboration Preserving Cultural Heritage, 1970-2012, explored how tribal museum utilized shared authority with their communities. For American Ancestors, Meaghan authored Ancestry of Secretary Lonnie G. Bunch II in 2023, and Ancestry of Douglas Brinkley in 2019. She co-authored with Chistopher C. Child, Family Tales and Trials: Settling the American South in 2020. She also contributed to Ancestors of Cokie Boggs Roberts with Kyle Hurst in 2016. She has published portable genealogists on African American Genealogy (2015) and Native Nations in New England (2020). Meaghan has authored several articles in her tenure for American Ancestors magazine including most recently, “10 Myths about Slavery in the United States.” She has presented many lectures on African American genealogy, researching enslaved ancestors, researching the history of a house, using oral history in genealogical research, researching women, and other topics.View all posts by Meaghan E.H. Siekman →