Detail of Leiden map, ca. 1600, a hand-colored engraving created by Pieter Bast, showing the Pieterskerk and surrounding area. Courtesy of Erfgoed Leiden en Omstreken (Heritage Leiden and Region)

Detail of Leiden map, ca. 1600, a hand-colored engraving created by Pieter Bast, showing the Pieterskerk and surrounding area. Courtesy of Erfgoed Leiden en Omstreken (Heritage Leiden and Region)

[Author's note: Part One appears here.]

In July, Tamura Jones collated the references to important dates in the Mayflower’s journey to New England to sort out when the Julian calendar is meant and when the Gregorian calendar is used. In the process, he pointed out that 31 July 2020 was the four hundredth anniversary of the Pilgrims’ departure from Leiden:

“The Mayflower Pilgrims left Leiden on 21 July 1620 of the Julian calendar. Commemorating that on 21 July 2020 of the Gregorian calendar makes no sense. You just cannot mix and match dates and calendars like that.

“There are two obvious candidate dates for the quadricentennial. If we were still using the Julian calendar, we would surely commemorate the departure on 21 July 2020 of the Julian calendar. However, because the world did switch to the Gregorian calendar, and the Pilgrims departed on that calendar’s 31 July 1620, we commemorate the departure on 31 July 2020. That last date is the right date, and not just because the Dutch were already using the Gregorian calendar. It is the right date because it is exactly 400 years later.”

Raymond Addison found, to his surprise, that what little he knew about one of his great-grandfathers, a native of Verona, would have to be discarded in favor of an unexpected place of origin:

Raymond Addison found, to his surprise, that what little he knew about one of his great-grandfathers, a native of Verona, would have to be discarded in favor of an unexpected place of origin:

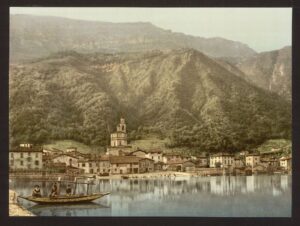

“I imagined Verona was just the metropolitan reference point that people would understand better, in the same way that I tell people that I am from Boston when I really am not. I learned, however, that Campione was not close to Verona and, in fact, it wasn’t even in Italy.

“Campione d’Italia is an Italian exclave within the borders of Switzerland. It is governed by Italy and is a part of the Lombardy region. How did this little town get this unique status? Campione is naturally separated from the rest of Italy by the Alps. Any images you find will show that the mountains around it are large enough to imply isolation. In conjunction with this geographic problem lies a history of government and religious authorities exchanging claims over the area. This happened until Italy unified in 1861.”

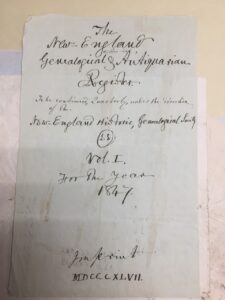

In September, Kyle Hurst reviewed some of the publishing initiatives undertaken by NEHGS from its founding in 1845:

In September, Kyle Hurst reviewed some of the publishing initiatives undertaken by NEHGS from its founding in 1845:

“In January 1845, according to the [Society’s record of its] proceedings, ‘a committee was appointed to prepare a circular for the use of the Society.’ That November, the Society formed a committee to publish a journal ‘devoted to the printing of ancient documents, wills, genealogical sketches and Historical and antiquaria matter generally.’ By January, the committee had arranged for bookseller Samuel G. Drake to finance the quarterly journal, including paying the $1,000 annual salary for Rev. William Cogswell, the first editor. With 700 subscribers, the first issue of the New England Historical and Genealogical Register came out in January 1847.

“Early in 1858, when 60-year-old Drake presided over NEHGS, he wished to change the society’s name to reflect that of the Register. The Massachusetts Historical Society protested that the change would make their names too similar. Because Drake failed to follow the correct procedures, the name change could not be made. Instead, on 25 May 1858 (Thomas Prince’s birthday), Drake and members of NEHGS formed the separate Prince Society for Mutual Publication. The group’s intention was to publish rare original historical works (in competition with the Massachusetts Historical Society) with the guarantee that Prince Society members would purchase the copies.

“In 1865, the Prince Society published The Hutchinson Papers, producing its first official volume in the series, one entitled Wood’s New-England Prospect. The group continued publishing volumes nearly annually until 1911, and had released a total of 35 by the time the group dissolved in 1943.”

Jeff Record demonstrated many of the approaches that lead to successful research in “Delayed messages,” including answers to those nagging questions that can feel both onerous and necessary:

Jeff Record demonstrated many of the approaches that lead to successful research in “Delayed messages,” including answers to those nagging questions that can feel both onerous and necessary:

“The only real clue we had about any of this was in Uncle Billy’s obituary. Survived by his wife, Horace Wilcox’s obituary stated only that he had been laid to rest in a ‘new and beautiful cemetery’ in the suburbs of Milwaukee. (Could they be any more vague?) Seeing as Uncle Billy had died in 1930, and that Aunt Minnie was later living with their son, Tom and I began looking through death indexes for every ‘Minnie Wilcox’ under the sun after 1930. Tom also checked out a doppelganger ‘Minnie Wilcox, widow of Horace G.’ in Colorado – but all this seemed to lead nowhere.

“Tom and I reasoned it likely that Minnie had not remarried (she was, after all, 67 years old when Uncle Billy died) and, further, that it was also likely that she was buried with Uncle Billy, or perhaps with her son Roy and her unloveable daughter in-law Clara Wilcox. But where were any of them? Alas, all we had to go on was that ‘new and beautiful’ unnamed cemetery in Milwaukee where Uncle Billy had been laid to rest. However, there was no record of Uncle Billy or Minnie, or of Roy or even Clara on FindAGrave, nor could we find any of them in any cemetery transcriptions or index. (Note to FindAGrave: We need a new search engine for sharp-tongued daughters-in-law…)”

Christopher C. Child wrote the year’s second-most-read post in November,[1] when he discussed Sir Winston Churchill’s new Mayflower line. Both posts are testimony to the abiding interest in the Mayflower and in Churchill, but it is also striking that Meaghan Siekman’s account of the native population that the English encountered on their arrival elicited a very strong reader response.

Christopher C. Child wrote the year’s second-most-read post in November,[1] when he discussed Sir Winston Churchill’s new Mayflower line. Both posts are testimony to the abiding interest in the Mayflower and in Churchill, but it is also striking that Meaghan Siekman’s account of the native population that the English encountered on their arrival elicited a very strong reader response.

Churchill’s ancestor was John3 Sprague: “His parents (of record), John Sprague and Ruth Bassett, were presented at the General Court of Plymouth on 6 June 1655 for ‘fornication before they were married’ and cleared after paying a fine. Generally, this charge meant that colonists ‘did the math,’ and realized a couple’s first child was born ‘too soon’ after they were married.

“Their eldest child, known later in life as Lt. John Sprague, was clearly regarded in several records as a child of John and Ruth. However the Y-DNA sequence of the descendants of Lt. John’s younger brothers Samuel and William showed these two (while sharing a father themselves), had a different father than their older brother Lt. John, and that Lt. John Sprague’s biological father had to be a member of the nearby Fuller family of Plymouth, for whom only Samuel2 Fuller (son of Mayflower passenger Samuel1 Fuller), was still in the area! So while John Sprague the elder likely assumed he was the natural father of his wife’s first child conceived before marriage, there was another candidate unknown to the Plymouth courts…”

In December, Pam Holland wrote about the multiple steps – forward and back, frequently lateral – that helped combine disparate references into one nineteenth-century immigrant:

In December, Pam Holland wrote about the multiple steps – forward and back, frequently lateral – that helped combine disparate references into one nineteenth-century immigrant:

“Eventually I was able to discover more records that proved I had the right naturalization. But to do this I looked at four kinds of records (census, city directory, birth, and church baptism) at four different websites (Ancestry, New York Public Library Digital Collections, FamilySearch, and FindMyPast). According to the 1896 naturalization, Charles McDermott the carpenter lived at 1119 Home St. I knew I needed to check city directories for more information. Unfortunately, Ancestry does not always have a directory for each year. However, I remembered that the New York Public Library Digital Collections does.

“Using both websites I discovered the following information for Charles McDermott…”

*

The year 2020 was yet another in which Vita Brevis posts stressed both the historic and the genealogical in the Society’s given name. History provides context, while the genealogical resolution to a problem strives to ensure that “Charles McDermott the carpenter” is also “Charles McDermott the fish grocer.” It seems to me that the genealogists I know are driven by curiosity and willing to go to great lengths to comprehend what can often be old research problems lacking easy resolution. Vita Brevis provides the setting for research breakthroughs, as well as guidance on how next to tackle a wearisome … a provoking … an addictively fascinating genealogical question.

Note

[1] The most-often-viewed post in 2020 was Meaghan E. H. Siekman’s “Before the Mayflower,” published in March.

Share this:

About Scott C. Steward

Scott C. Steward has been NEHGS’ Editor-in-Chief since 2013. He is the author, co-author, or editor of genealogies of the Ayer, Le Roy, Lowell, Saltonstall, Thorndike, and Winthrop families. His articles have appeared in The New England Historical and Genealogical Register, NEXUS, New England Ancestors, American Ancestors, and The Pennsylvania Genealogical Magazine, and he has written book reviews for the Register, The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, and the National Genealogical Society Quarterly.View all posts by Scott C. Steward →