As 2020, the year commemorating the four hundredth anniversary of the Mayflower landing in the New World, comes to a quiet end we can, with hopefulness, look forward in 2021 to making up for all the 2020 cancellations by commemorating the quadricentennial of many first-year Mayflower milestones. The “Winter of Death” and the death of the colony’s first governor, John Carver, were despairing events, but other milestones, including the treaty signed with Massasoit in March 1621, the first marriage in the Pilgrim village in May, and the harvest feast in late October lifted the colony’s hopes. The year 2021 should, in more ways than one, be recognized as the year of survival.

As 2020, the year commemorating the four hundredth anniversary of the Mayflower landing in the New World, comes to a quiet end we can, with hopefulness, look forward in 2021 to making up for all the 2020 cancellations by commemorating the quadricentennial of many first-year Mayflower milestones. The “Winter of Death” and the death of the colony’s first governor, John Carver, were despairing events, but other milestones, including the treaty signed with Massasoit in March 1621, the first marriage in the Pilgrim village in May, and the harvest feast in late October lifted the colony’s hopes. The year 2021 should, in more ways than one, be recognized as the year of survival.

In an effort to make the most of the current year, despite cancellations and restrictions, I’ve made numerous visits to Plymouth, immersing myself in Pilgrim history. A favorite spot to pause and reflect has been the historic Burial Hill, where Pilgrim history intersects with colonial history and folk art, commanding views of the coastline and, with a little imagination, a sense of what the Pilgrims might have experienced sailing into the harbor from across the bay. The realized promise of the Pilgrim colony, its survival, has its tangible legacy in any number of the individuals who are buried in the cemetery, generations who could trace their ancestry to Mayflower passengers.

Notable among those descendants are Revolutionary War Patriots, including Plymouth-born James Warren (1726-1808), who is buried with his Barnstable-born wife, the poetess and pamphleteer Mercy Otis (1728-1814), the daughter of James Otis Sr. and the sister of firebrand James Otis Jr. James Warren was a descendant of Mayflower passengers Richard Warren and Edward Doty. His wife, Mercy, was also a descendant of Edward Doty. More than a century and a half after these ancestors had taken their perilous journey, the revolutionaries began their own, also against the odds.

Nearly eighty Revolutionary War graves are scattered across Burial Hill and on one far edge of the cemetery a marble obelisk memorializes a Revolutionary War event that is especially remembered at Christmastime. Back in August, when I wrote a post about the collection of town plans at the Massachusetts State Archives, I mentioned the Plymouth plan and, on it, a notation to Captain Magee’s shipwreck. I promised to return to that notation with a fuller explanation.[1]

By 1778, Captain Magee had taken command of the newly-built 100-foot privateer brig General Arnold...

Less well-known than his fellow Revolutionary War Patriots, Captain James Magee was born in County Down in 1750 and emigrated to New England just before the Revolution. Very little is known about him prior to his arrival, and the first certain reference to him in America appears to be in 1777, when he commanded the privateer Independence, one of a fleet of privately-owned vessels licensed by the states to serve as makeshift warships with the purpose of disrupting British shipping and capturing “prizes.” By 1778, Captain Magee had taken command of the newly-built 100-foot privateer brig General Arnold, mounting twenty guns and with a crew of 105 men and boys.

The General Arnold must have appeared an intimidating adversary, but no sooner had it sailed out of Boston Harbor at sunrise on Christmas Day 1778 when it met a formidable foe: an unusually violent nor’easter bearing down on the area. Continuing along the coast, twenty-eight-year-old James Magee made the fateful decision to seek refuge from the storm in Plymouth Harbor where, during the night, despite preparations and precautions to secure the vessel, gale winds ripped it loose from its anchors and drove it onto the shallows of White Flat, a treacherous shoal just off Plymouth Beach.

For thirty-six hours the sea broke over the General Arnold, flooding its below-decks with freezing water, entombing the vessel in ice and snow and wedging her keel deeper and deeper into the sand. Though the vessel had foundered only a mile from shore and the distress of its crew was plainly visible from the town, the frozen shoreline, extreme cold, and churning seas thwarted rescue attempts. Desperate to stay warm, crew members broke into casks of brandy as Captain Magee pleaded with them to pour the “liquid warmth” into their boots to prevent frostbite. Instead, in their delirium, the men consumed the brandy, their intoxication and fatigue rendering them even more vulnerable to sleep and the bitter cold. Together they huddled on the deck and not until Monday, December 28, when the storm abated, were rescuers able to reach the vessel, by then a scene of human misery.

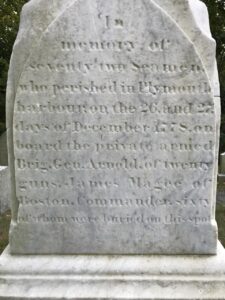

In his 1832 History of the Town of Plymouth, Dr. James Thacher (1754-1844), a surgeon in the Continental Army and a founder of the Pilgrim Society (1820), recounted the carnage as an “appalling spectacle.” Seventy crew members had frozen to death “into all imaginable postures,” their “features dreadfully distorted.” Another thirteen died soon after being brought ashore. Laid in Town Brook to thaw and then taken to the courthouse in Town Square where the townspeople of Plymouth came to mourn, sixty crew members were buried in a common grave on Burial Hill, a grave that was unmarked until 1862, when a man named Stephen Gale of Portland, Maine, heard the story of the General Arnold. Though unrelated to any of the mariners, he paid for the obelisk to mark their grave.

In his 1832 History of the Town of Plymouth, Dr. James Thacher (1754-1844), a surgeon in the Continental Army and a founder of the Pilgrim Society (1820), recounted the carnage as an “appalling spectacle.” Seventy crew members had frozen to death “into all imaginable postures,” their “features dreadfully distorted.” Another thirteen died soon after being brought ashore. Laid in Town Brook to thaw and then taken to the courthouse in Town Square where the townspeople of Plymouth came to mourn, sixty crew members were buried in a common grave on Burial Hill, a grave that was unmarked until 1862, when a man named Stephen Gale of Portland, Maine, heard the story of the General Arnold. Though unrelated to any of the mariners, he paid for the obelisk to mark their grave.

Among the survivors of the “Magee storm” was Barnabas Downs, born in Barnstable in 1756, to farmer Barnabas Downs (1730-1820) and his first wife Mercy Lumbert (1733-ca. 1758). After serving as a soldier for three campaigns during the Revolutionary War, Downs shipped aboard privateers. Eight years after the wreck of the General Arnold, he wrote a brief account of his harrowing experience, deliverance from near-death, his gradual recovery, and the subsequent amputation of his frostbitten legs.[2] Of the twelve Barnstable men who were aboard the General Arnold, Downs was the only one who survived, though as he lay motionless on the deck he was initially passed over as dead until rescuers noticed his eyelids moving. Despite his hardships, in 1784 he married Sarah Hamblin and fathered five children, the first of whom he named James Magee Downs in honor of Captain Magee.

In his notes about the Downs family, Barnstable genealogist Amos Otis (1801-1875) wrote that Barnabas Downs was “honest and industrious, and though he went about on his knees, he worked in his garden in pleasant weather, cut up his wood, and did many jobs about the house. In the winter, and during unpleasant weather he coopered for his neighbors.” He was a pious man, noted Otis, “and being considered a worthy object of charity, a collection was annually taken up for his benefit by the church.” He lived comfortably and respectably until his death in 1817.[3]

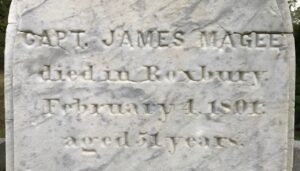

Captain James Magee, said to have never despaired throughout the ordeal, staying calm and encouraging his crew by his example, survived the wreck physically unscathed, though his ill-fated decision of December 25, 1778 and the loss of so many Patriots haunted him for the remainder of his life. For several years after the wreck, he continued to serve the Patriot cause and later commanded merchant ships out of Salem. In 1783 he married Margaret Elliot – with whom he would have nine children – and in 1789 was at the helm of the vessel Astrea when it sailed into Canton, one of the first ships to begin American trade with China. During the 1790s, Magee became a prominent figure in the China trade and a wealthy man.

Though living a comfortable life, Captain James Magee never forgot the dreadful night of December 25, nor the crew of the General Arnold...

Though living a comfortable life, Captain James Magee never forgot the dreadful night of December 25, nor the crew of the General Arnold. In 1798 he moved from Boston’s Federal Street to Shirley Place in fashionable and bucolic Roxbury. Built between 1747 and 1751, the 33-acre estate, with its extensive orchards and sweeping views of the harbor, had been the seasonal home of royal governor William Shirley; it is, today, a National Historic Landmark, the only country house in America built by a British royal colonial governor.[4] While living on Federal Street and, later, in Roxbury, Captain Magee hosted holiday parties for the surviving General Arnold crew members and their families, and for the widows and children of those lost. Accepting full responsibility for the fate of the General Arnold and ever mindful that another privateer departing Boston alongside the General Arnold had made a different decision, successfully riding out the storm at sea off Cape Cod, Captain Magee endeavored to assist the families in any way that he could.

When he died in 1801 at the age of fifty-one, it was said that his final wish was to be laid to rest on Burial Hill with his crew members. The Boston newspapers, publishing his death notice, reported that his funeral “will proceed from his late dwelling-house” and that “friends and acquaintances of the deceased are requested to attend his interment, without a more particular invitation.” In all likelihood, Captain James Magee was buried in a family tomb in Boston’s Central Burying Ground, where at least six other family members are interred. The Trustees of Shirley Place, now the Shirley-Eustis House, remember Captain Magee, a “convivial, noble-hearted Irishman,” each Christmas season with an eighteenth-century-inspired holiday party complete with festive greenery and wreaths, meringues and macaroons, music, dancing, and Captain Magee’s famous Fish House punch.

When he died in 1801 at the age of fifty-one, it was said that his final wish was to be laid to rest on Burial Hill with his crew members. The Boston newspapers, publishing his death notice, reported that his funeral “will proceed from his late dwelling-house” and that “friends and acquaintances of the deceased are requested to attend his interment, without a more particular invitation.” In all likelihood, Captain James Magee was buried in a family tomb in Boston’s Central Burying Ground, where at least six other family members are interred. The Trustees of Shirley Place, now the Shirley-Eustis House, remember Captain Magee, a “convivial, noble-hearted Irishman,” each Christmas season with an eighteenth-century-inspired holiday party complete with festive greenery and wreaths, meringues and macaroons, music, dancing, and Captain Magee’s famous Fish House punch.

In his Downs family essay, Amos Otis paid tribute to the townspeople of Plymouth and their Mayflower legacy. “On the sea coast,” he wrote, “in all parts of the world, there are ‘moon cursers,’ that is men who hold that it is no sin to steal from a shipwrecked mariner. To the everlasting honor of the Plymoutheans, they had not forgotten the rigid morality taught by their Pilgrim fathers – there were no ‘moon cursers’ there. Capt. Magee, the friends of the deceased who went from Barnstable, and the Vineyard, bear one testimony – every article recovered from the wreck was perfectly preserved, and returned to its rightful owner or to his heirs. The history of Plymouth will be studied as long as man exists, and the two facts we have named will ever be bright jewels in her diadem, namely, the noble generous hospitality which her sons and daughters extended to the shipwrecked mariners of the General Arnold, and second, the scrupulous honesty they displayed in restoring every article found, however small in value, to its rightful owner.”

Barnstable-born Dr. James Thacher, whose gravesite is also on Burial Hill had, like Amos Otis, reflected on the Pilgrim story and recognized it as a unifying theme. In 1775, on his way to join the Continental Army in Cambridge, Thacher stopped at Plymouth to view Plymouth Rock, “which received the first footsteps of our venerated forefathers.” Writing in his journal, Thacher asked, “Can we set our feet on their rock without swearing, by the spirit of our fathers, to defend it and our country? If we reflect on their matchless enterprise, their fortitude, and their sufferings, we must be inspired with the spirit of patriotism, and the most invincible heroism.”[5]

Notes

[1] "Making Plans," Vita Brevis, August 13, 2020.

[2] Barnabas Downs, A brief and remarkable Narrative of the Life And extreme Sufferings of Barnabas Downs, Jun., 1786.

[3] For an interesting discussion about Otis’ Genealogical Notes of Barnstable Families and a connection to NEHGS, see The New England Historical and Genealogical Register 52 [1898]: 206.

[4] The estate remained in the Magee family until 1819, when it was sold to William Eustis, physician and statesman. After a number of occupants contributed to its disrepair, the house was abandoned in 1911. In 1913 it was purchased by the Shirley-Eustis House Association. Restoration began in 1980 and the house opened to the public in 1991.

[5] Dr. James Thacher’s military journal can be found at AmericanRevolution.org

Share this:

About Amy Whorf McGuiggan

Amy Whorf McGuiggan recently published Finding Emma: My Search For the Family My Grandfather Never Knew; she is also the author of My Provincetown: Memories of a Cape Cod Childhood; Christmas in New England; and Take Me Out to the Ball Game: The Story of the Sensational Baseball Song. Past projects have included curating, researching, and writing the exhibition Forgotten Port: Provincetown’s Whaling Heritage (for the Pilgrim Monument and Provincetown Museum) and Albert Edel: Moments in Time, Pictures of Place (for the Provincetown Art Association and Museum).View all posts by Amy Whorf McGuiggan →