This is a tale of how curiosity, knowledge of local Italian sources and conditions, and focused research strategies uncovered an error in church records and solved a genealogical mystery. Last year I finally discovered that my immigrant great-great-grandfather Antonio Pugni (1840-1913) was from the village of Coli in Piacenza, Italy. Fortunately, Coli parish church records of baptisms, marriages, and deaths date to 1718, and in some instances to the 1690s, and can be accessed directly on FamilySearch.org. Civil registration records of births, marriages, and deaths begin in 1806 and are also online at FamilySearch, but images can be viewed only at any of the 5,000+ Family History Centers worldwide.

Genealogists rightly prize original records, and are grateful to find hundreds of years of vital records from a trusted source like churches, especially when they are the only records that exist or are accessible for extended periods. Using these records, written in Latin by the parish priests, I have documented all my ancestral lines in Coli to at least the 1700s. However, fortuitous circumstances led me to question whether a 1750 baptism record had mistakenly identified the family name. Relying on what I learned about patterns of life, culture, and clerical record-keeping in eighteenth-century Coli, and employing various research strategies, I was able to determine that this baptism record was in fact incorrect and to identify the correct family. Having sorted this out, I thought it worthwhile to share this tale for the benefit of other researchers who might encounter similar circumstances.

My intensive research in parish registers not only yielded several generations of new ancestors, but also revealed important facts about life and death in Coli. Child mortality was high – indeed, almost all of my ancestral families lost one or more of their children, and many adults died prematurely. Occasionally I found a death record for a child for whom there was no baptism record, so the death record was the only documentation of its brief life. Young widow(er)s with families often remarried within a year or two of losing spouses and had more children.

Children took their father’s surname, and females retained their maiden names throughout life, but parish registers did not record names consistently.

Couples usually had children every 2 to 3 years during their childbearing period of about 20 years, and if two children were given the same name at baptism, it generally meant that the first had died. Additionally, customary naming patterns frequently resulted in multiple people with the same names living at the same time in the same community, so paying attention to their specific neighborhoods (e.g., Villa Gavi, Villa Porcile … when such information was recorded) was essential to distinguish them. Children took their father’s surname, and females retained their maiden names throughout life, but parish registers did not record names consistently. One variously finds the full names of both spouses, sometimes with the names of one or both of their parents; or the full name of the husband but only the wife’s first name; and death records usually name the deceased’s parents or spouse, and may indicate widow(er) status.

This understanding of local demographic and cultural patterns and record-keeping practices informed my research strategies, and was key to discovering and correcting the baptism register error. Whenever I identify new direct ancestors, I first look for their marriage records. If found, I then try to find all of their children in the baptism records, beginning a year or two before their marriage (in case they had a child out of wedlock) and extending about 30 years thereafter (in case the wife married very young and/or had an unusually long fertility period, or one of the spouses died, remarried, and had more children).

If no marriage record is found (perhaps because they married in another parish), I also turn to the baptism records, where I use the baptism date of that child who is in my ancestral line as a starting point. Working backwards and forwards, I continue at least 10 years past the last baptism record for that family, to be sure I have found all their children. Next I examine death records for the couple’s childbearing years plus about 20 years beyond, to identify children who died and to determine whether either of the parents perished. If I observe an unusually short childbearing period, or one of the parents died, I search marriage records again to see if the widow(er) remarried.

So, how exactly did a fortuitous mix of curiosity, understanding of local Italian sources and conditions, and focused research strategies lead to the discovery and correction of an error in the Coli baptism registers, and solving a genealogical puzzle? I was researching the family of Domenico Plate (c. 1700-1785) and Blanca Peveri (c. 1714-1774) of Villa Braschi, one pair of my great-great-great-great-great-great-grandparents. They married in 1736, and I found five children born between 1737 and 1754, but noticed an unusual 7-year gap in births between 1747 and 1754.

They married in 1736, and I found five children born between 1737 and 1754, but noticed an unusual 7-year gap in births between 1747 and 1754.

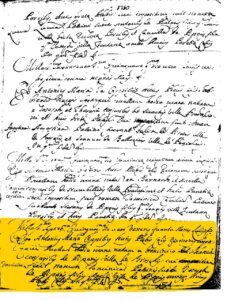

Out of curiosity, and concerned that I might have overlooked a baptism record, I again reviewed baptisms during those years but found none. However, another record caught my eye because the names of the parents were similar: the 1750 baptism of Domenica, born to Domenico and Blanca Peveri of Villa Braschi. A straightforward reading of this entry, consistent with record-keeping practices, was that Domenica was the child of Domenico Peveri and his wife Blanca (surname unstated). However, I wondered whether the priest might have recorded the family name incorrectly, a possibility all the more likely because my Blanca’s maiden name was Peveri. If there was a Domenico Peveri of Villa Braschi with a wife named Blanca having children around this time, there should be other baptism records for them in the years before and/or after 1750.

To test this supposition, I reviewed all baptisms for 10 years on either side of 1750, but didn’t find a single record for a child whose parents were Domenico Peveri and wife Blanca. As another independent check on my surmise, I reviewed marriage records 1730-1750, but did not find any for a Domenico Peveri. Apparently, notwithstanding what was recorded in this baptism entry, there was no married couple in mid-eighteenth-century Coli named Domenico Peveri and wife Blanca!

I thus concluded that the priest did indeed err, and it’s easy to conjecture how this might have happened. Following his own record-keeping style, he intended to write “Domenicus et Blanca Plate,” but knowing that Blanca was a Peveri, he absentmindedly wrote her surname instead. Whatever the circumstances, I accepted this 1750 baptism record for Domenica as a child of Domenico Plate and Blanca Peveri, and added her to my family tree.

Share this:

About Joe Smaldone

Joe Smaldone and his wife Judy Warwick Smaldone have been researching their family’s history for more than 20 years. Their research has taken them to many national, state, and local libraries, archives, court houses, churches, cemeteries, historical and genealogical societies, and other research sites across the United States, and abroad to Ireland, Italy, and Sweden. They are members of NEHGS and the New York Genealogical and Biographical Society. Joe was an adjunct professor at Georgetown University, where he created and taught a course entitled Your Family in History. He is a Genealogy Research Consultant at the FamilySearch Center, Annapolis, Maryland, and has published numerous genealogical studies, articles, abstracts, blog posts, and indexes.View all posts by Joe Smaldone →