[Editor's note: This blog post originally appeared in Vita Brevis on 22 July 2019.]

My great-grandfather John W. Rhodes lived in Wareham, Massachusetts for most of his life. Though I remember him well, I knew nothing of his extended family. His 1966 obituary named Eva (Rhodes) Clancy of Westerly, Rhode Island, as a surviving sister. Sixteen years later, I hoped some members of the Rhodes family still lived there as I prepared for my first of many trips to Westerly.

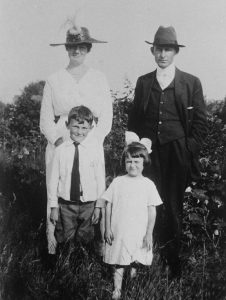

Westerly town directories revealed Eva Clancy lived at 155 Granite Street, and after her death in 1980, Eva’s daughter Mary Clancy remained at the same address. Happy to meet a new, previously unknown relative, Mary and her cousin Alma Rhodes provided me with a wealth of information. The last surviving member of a large family, Evangeline [shortened to Eva] Rhodes was born in Westerly on 2 April 1892, her mother’s tenth child. Eva’s father, William Rhodes, an immigrant from Newton Abbot, Devon, England, was already a widower with two small sons when he married 27-year-old Mary Counihan, an Irish-born widow.

While William remained an Episcopalian, Mary insisted upon Catholic baptism for all the Rhodes children. In their first 13 years of marriage, Mary Rhodes gave birth to nine children in five different locations. Then her husband landed a permanent job in Westerly. After Eva, Mary had three more children, her last at the age of 48. Mary Rhodes died in August 1907 from pulmonary tuberculosis, leaving Eva as the only daughter at home.[1]

According to Mary Clancy, her mother Eva at 16 married 25 year-old-James Clancy because she did not want to keep house for her recently widowed father and brothers. After marriage, Eva moved in with her Clancy in-laws at 155 Granite Street where she and gave birth to four children. One child died in infancy and another at the age of six.

Another tragedy struck in 1933, as James Clancy, only 49, slowly succumbed to silicosis, “stone-cutter’s consumption.” Eva cared for husband at home – and one image endures among other shared memories: Eva shaved her bedridden husband when he was no longer able to stand. When James Clancy died, his son Jack was a first-year medical student at the University of Rhode Island. Eva offered to mortgage the house to finance Jack’s education; Jack declined and went to work to support his mother.

Throughout Eva’s long years of widowhood, she never complained about life’s vicissitudes. She never remarried, combining her domestic duties with writing poems and making hats, which became her daughter Mary’s trademark at the local courthouse where she worked.

My continued visits to Westerly eventually resulted in a Rhodes family genealogy circulated among my cousins. Some facts were missing: Eva’s granddaughter asked why I did not include a specific date for her grandparents’ marriage, circa 1908. “Because I could find any record in Westerly, elsewhere in Rhode Island, or nearby Connecticut towns,” I replied. Feeling that I had not perhaps searched thoroughly enough, I subsequently visited Westerly’s Immaculate Conception Church, where Eva and James’s marriage took place on 12 May 1909.

A marginal notation, with a dispensation for reading three banns of marriage, raised a red flag: Eva’s eldest child was born the previous month. I surmised, under these circumstances, that a discreet priest simply did send a copy of the marriage to the town clerk. My next revision of the Rhodes genealogy included the date and location of Eva and James’s marriage without further comment. Eva’s granddaughter later exclaimed, “The date can’t be right! My grandmother wasn’t like that.” I had no further explanation – almost 25 years elapsed before I considered the issue once again.

These marriages would not have been considered valid in the eyes of the Catholic Church.

Then it clicked! My research experience among many early nineteenth-century French-Canadian immigrants to Vermont encountered some couples, in the absence of a priest, who were married by a justice of the peace or a non-Catholic clergyman. These marriages would not have been considered valid in the eyes of the Catholic Church. Eventually, couples wanting their children to be baptized and raised as Catholics would seek a “rehabilitation,” or the legitimization of their union. A Catholic Church marriage, with a priest, two witnesses, and reading of banns often followed within a year of two after the initial marriage; others took much longer.

Church registers vary in indicating a rehabilitated marriage. Thanks to the ever-expanding digitization of indexes leading to genealogical records, I searched again for Eva’s marriage. Eureka! Eva Rhodes and James Clancy eloped to New York City. They were married by a Justice of the Peace on 30 November 1908, seven months before their church marriage in Westerly. Though I missed it the first time around, the church record in Westerly represented the rehabilitation of a previous act of marriage.

Note

[1] For more on the Rhodes family, see Michael F. Dwyer, “Mary Rhodes: An Arduous Journey to Westerly,” Rhode Island Roots 37 [2011]: 17–27.

Share this:

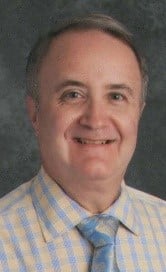

About Michael Dwyer

Michael F. Dwyer first joined NEHGS on a student membership. A Fellow of the American Society of Genealogists, he writes a bimonthly column on Lost Names in Vermont—French Canadian names that have been changed. His articles have been published in the Register, American Ancestors, The American Genealogist, The Maine Genealogist, and Rhode Island Roots, among others. The Vermont Department of Education's 2004 Teacher of the Year, Michael retired in June 2018 after 35 years of teaching subjects he loves—English and history.View all posts by Michael Dwyer →