Well, for what looked like it was going to be an awesome year … even in Roman numerals (MMXX) … 2020 is set to go down in history as one of the most trying ever! When so much of what we typically learn about history is painted by textbooks in wide, sweeping gestures, it can be illuminating to read the granular experiences of individuals. I’ve seen several small museums publishing requests for their patrons to keep diaries now, and sharing items online from their collections illustrating the importance of first-person history. In this spirit, I thought I would share a few accounts written by my own ancestors who lived through momentous events.

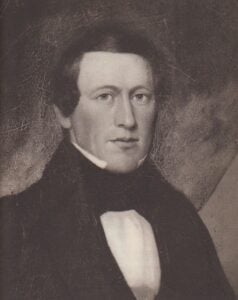

This first example is from an undated letter (by context it’s from October 1857) sent by my great-great-great-grandfather James Frederick Athearn (1810-c.1870) in Boston to business associates/relatives on Nantucket. It is excerpted from one of eighty-two letters held in the collections of the Nantucket Historical Association, and through several of them, I learned about the first global financial crisis in modern history. (I also learned that correct capitalization and punctuation were not a priority for my ancestor, so I’ve added some help in brackets!)

Mrss Chs G & H Coffin[1]

Gents

… I like to act promptly lest some unfavourable change should occur in New York[. We] doe not know yet how the Banks will fare in that city[;] they may yet be driven into liquidation[. If] so it will be deplorable then and no help for the merchants can be expected[.]

[The] fashionable way here is not to fail but advertise to meet your payments six months from maturity[. You] will see an article in the Transcript in the form of burlesque…

Yrs James

Can you use any other money to pay debts with except Massachusetts money[?][2] [If] so R[hode] Island money can be got at a discount here[;] it will answer for every thing except to pay notes here[.]

JFA

This next first-person account comes from my great-grandfather, Fred Goodrich Athearn (1874-1956), and recounts his experience of the San Francisco Earthquake:

On the morning of April 18, 1906, I was in a private business car running special, east, on the Tucson Division of the Southern Pacific Railroad, bound for El Paso. Upon reaching Lordsburg, New Mexico, we were handed a telegram that told us of the great earthquake and fire that had occurred in San Francisco in the morning. The message was most lurid and startling. Subsequent dispatches told of the thousands of persons that had been killed by the earthquake, and that a fire was sweeping the city, rendering other thousands homeless.

I was filled with apprehension lest something should have happened to my beloved wife,[3] for we were expecting a baby in August of that year. I immediately turned back and went to Tucson, at which point I boarded a special train to San Francisco.

Upon our arrival at Los Angeles, the depot was crowded with people either waiting to meet friends and relatives who were fleeing San Francisco, or trying to get passage to San Francisco. I telephoned to my wife’s sister who lived in Los Angeles, and she came to the depot to see me. Everyone was trying to dissuade us from going on to San Francisco. We were told that so many people had perished in the earthquake and fire that health authorities were loading the bodies onto boats and burying them at sea; that there was no food; that the banks were all destroyed and no money was to be had. It was truly a frightening picture. My wife’s sister gave me twenty dollars, a ham, two loaves of bread, and other foodstuffs.

Finally my train started and in the afternoon of April 21, I arrived at the Sixteenth Street Station of the Southern Pacific Company in Oakland, just across the bay from San Francisco. My train was boarded there by some soldiers and everyone was told to detrain at once, as passengers would not be allowed to go to the pier, the usual terminal for trains. We were informed that no one would be permitted to cross the bay to San Francisco. I refused to get off the train and showed the soldiers my credentials and told them I was an officer of the Southern Pacific Company.

I forthwith secured a military pass and proceeded to San Francisco. As we got off the ferryboat on the San Francisco side, we were halted by the military police. One of the soldiers threateningly held a bayonet rather close to another man’s middle and ordered him to halt.

In those days there were very few automobiles. How to get to where my wife was staying was a problem. I figured out that she was probably not in the house but in a vacant lot about two or three lots away from where the house stood. Fortunately, her mother[4] was visiting her. I finally succeeded in getting a one-horse express wagon, for a fee of twenty dollars, to take me to Hugo Street. I went directly to the vacant lot and, sure enough, there were Evelyn and her mother, camping out.

I was determined to get my wife and her mother out of San Francisco; slight earthquakes were occurring about every 15 or 20 minutes, the whole town was still ablaze, and buildings were being blown up with dynamite to stop the progress of the fire. I finally got Evelyn and her mother down to the ferryboat and went over to Oakland. There was no place to get anything to eat, but I was told people were being fed on the campus of the University of California at Berkeley. So we went on to Berkeley and, with the many others, lined up and got beans and coffee for dinner.

This final excerpt comes from the five-year diary that my grandmother, Rachel Louise (Kortge) Christy (1916-2004), received from her husband on their first anniversary. I apologize that, like many historic records, it reflects previous norms that are offensive to modern readers. The day after my grandmother mentioned plans for her mother’s upcoming surprise sixtieth birthday party, she wrote about her new temporary job at a Portland, Oregon, department store:

This final excerpt comes from the five-year diary that my grandmother, Rachel Louise (Kortge) Christy (1916-2004), received from her husband on their first anniversary. I apologize that, like many historic records, it reflects previous norms that are offensive to modern readers. The day after my grandmother mentioned plans for her mother’s upcoming surprise sixtieth birthday party, she wrote about her new temporary job at a Portland, Oregon, department store:

December 6, 1941: Started work at Olds & Kings. Like it fine. Get to work until Xmas.

December 7, 1941: Japs attacked Pearl Harbor. Surprise and shock to everyone.

December 8, 1941: War has certainly hurt business.

It was several days before Grammy got around to writing further entries. Not only are there no details about the big party planned for December 13 (if that ever happened), she even omitted recording her sister’s sudden marriage on December 20 … but these things happen when you are living through historic events.

Notes

[1] Charles Gardner Coffin (1801-1882) and Henry Coffin (1807-1900) were brothers and co-owners of a whale oil shipping firm. Henry’s wife, Eliza Starbuck (1811-1903), was the older sister of James F. Athearn’s wife, Lydia Ramsdell Starbuck (1813-1889). By coincidence, Henry’s great-great-grandson is married to Brenda Williams, the NEHGS Counselor featured on page 8 of the Spring 2020 issue of American Ancestors.

[2] It was not until 1862 that the Federal government of the United States began to print banknotes, and individual banks continued to issue their own banknotes until the 1930s.

[3] Purle Evelyn (Bottom[e]s) Athearn (1878-1941), whose century-old book club is still going strong.

[4] Aurelia Jane (Hargrave) (Bottom[e]s) Corker (1847-1925), whose revolutionary sentiments were featured six months ago.

Share this:

About Pamela Athearn Filbert

Pamela Athearn Filbert was born in Berkeley, California, but considers herself a “native Oregonian born in exile,” since her maternal great-great-grandparents arrived via the Oregon Trail, and she herself moved to Oregon well before her second birthday. She met her husband (an actual native Oregonian whose parents lived two blocks from hers in Berkeley) in London, England. She holds a B.A. from the University of Oregon, and has worked as a newsletter and book editor in New York City and Salem, Oregon; she was most recently the college and career program coordinator at her local high school.View all posts by Pamela Athearn Filbert →